John Quincy Adams (12 page)

Authors: Harlow Unger

John Quincy's essays put his name before Boston's public just as a banking collapse was producing a windfall of legal work from investors trying to recoup their losses. “The bubble of banking is breaking,” he wrote to his father. “Seven or eight failures have happened within these three days, and many more are inevitable in the course of the ensuing week. The pernicious practice of mutual endorsements upon each other's notes has been carried . . . to an extravagant length and is now found to have involved not only the principals, who have been converting their loans from the bank into a regular trading stock, but many others who have undertaken to be their security.”

27

27

“The late failures in Boston,” Abigail beamed as she wrote to her husband after visiting John Quincy, “have thrown some business into the hands of our son. He is well and grows very fat.”

28

28

John Quincy Adams grew fatter in the days that followed. By early 1793, events overseasâand their repercussions in Americaâhad intensified the divisions between Americans who supported the French Revolution and its opponents. President George Washington pleaded for national unity, saying it would be “unwise in the extreme . . . to involve ourselves in the contests of European nations.”

29

When newspapers ignored his pleas, Washington considered a formal proclamation of neutrality to ensure American independence from both English and French influence.

29

When newspapers ignored his pleas, Washington considered a formal proclamation of neutrality to ensure American independence from both English and French influence.

In France, Jacobin extremists had seized control of the four-year-old revolution, overturned the monarchy, sent King Louis XVI to his death on the guillotine, and discarded the constitution. On February 1, 1793, France declared war on Britain, Holland, and Spain. Under the Franco-American alliance of 1778, each nation had pledged to aid the other in the event of an attack by foreign enemies, and France now demanded that the United States join her war against Britain. In April, Edmond Genet, the new minister plenipotentiary to the United States, bypassed normal diplomatic protocol

and appealed to the American people to pressure the President and Congress to join the French war against England.

and appealed to the American people to pressure the President and Congress to join the French war against England.

Â

French ambassador Edmond Genet arrived in the United States with secret plans to incite rebellion against the Washington administration and install a government that would join France in war against Britain.

(FROM A NINETEENTH-CENTURY ENGRAVING)

(FROM A NINETEENTH-CENTURY ENGRAVING)

“In the United States,” the French minister cried out, “men still exist who can say, âHere a ferocious Englishman slaughtered my father; there my wife tore her bleeding daughter from the hands of an unbridled Englishman,' and those same men can say, âHere a brave Frenchman died fighting for American liberty; here French naval and military power humbled the might of Britain.'”

30

30

Secretary of State Jefferson hailed Genet's arrival. “The liberty of the whole earth depends on the success of the French Revolution,” Jefferson exulted as he urged Washington to support the French. “Nothing should be spared on our part to attach France to us. Failure to do so would gratify the combination of kings with the spectacle of the only two republics on earth destroying each other.”

31

31

Outraged by Jefferson's embrace of French revolutionaries “wading through seas of blood,” Treasury Secretary Hamilton argued against American participation, calling it self-destructive. He reminded the President that Britain remained America's most important trading partner, buying the majority of her exports, producing the majority of her imports, and yielding most of the government's revenues through import duties. To war beside France against Britain, Hamilton asserted, was not only economically suicidal but morally indefensible. Riding a wave of popularity in Boston, John Quincy marched into the fray to support the President: “To advise us to engage voluntarily in the war,” he declared, “is to aim a dagger at the heart of this country.”

We have a seacoast of twelve hundred miles everywhere open to invasion, and where is the power to protect it? We have a flourishing commerce expanding to every part of the globe, and where will it turn when excluded from every market on earth? We depend upon the returns of that commerce for many necessaries of life, and when those returns shall be cut off, where shall we look for the supply? We are in a great measure destitute of the defensive apparatus of war, and who will provide us with the arms and ammunition that will be indispensable? We feel severely at this moment the burden of our public debt, and where are the funds to support us in the dreadful extremity to which our madness and iniquity would reduce us?

32

32

John Quincy's words anticipated those of the President. With the United States all but defenseless, without a navy and only a minuscule army in the West fighting Indians, the President knew he could not risk war with Englandâor any other nation, for that matter. As John Quincy had noted, the powerful British navy could easily blockade American ports and shut coastal trade, while the British military in Canada could combine with Spanish forces in Florida and Louisiana to sweep across the West and divide it up between them. Washington agreed with Hamilton that France had embarked on an offensive, not a defensive, war and that the Franco-American treaty of 1778 did not apply. He also saw the economic good

sense of seeking a rapprochement with England and issued the neutrality proclamation he had been considering.

sense of seeking a rapprochement with England and issued the neutrality proclamation he had been considering.

“It behooves the government of this country,” the President told Congress, “to use every means in its power to prevent the citizens . . . from embroiling us with either of these powers [England or France] by endeavoring to maintain a strict neutrality. I therefore require that you will . . . [take] such measures as shall be deemed most likely to effect this desirable purpose . . . without delay.”

33

33

John Quincy seconded the President, stating that “an impartial and unequivocal neutrality . . . is prescribed to us as a duty.”

34

34

Genet, however, responded differently, buying boldfaced newspaper advertisements that called on “Friends of France” to ignore Washington's Neutrality Proclamation and enlist in the French service to fight the British. “Does not patriotism call upon us to assist France?” his advertisements asked. “As Sons of Freedom, would it not become our character to lend some assistance to a nation combating to secure their liberty?”

35

35

Francophiles across the United States rushed into the streets to protest the President's stance and demand that Congress declare war against Britain. An estimated 5,000 supporters rallied outside Genet's hotel in Philadelphia and set off endless demonstrations that raged through the night into the next dayâand the next. Vice President Adams described “the terrorism excited by Genet . . . when 10,000 people in the streets of Philadelphia, day after day, threatened to drag Washington out of his house and effect a revolution in the government or compel it to declare war in favor of the French Revolution and against England.” Adams “judged it prudent and necessary to order chests of arms from the war office” to protect his house.

36

Fearing for the safety of his wife and grandchildren, Washington made plans to send them to the safety of Mount Vernon.

36

Fearing for the safety of his wife and grandchildren, Washington made plans to send them to the safety of Mount Vernon.

Adding to the turmoil was the sudden arrival of the French fleet from the Antilles. Genet ordered gangways lowered and sent French seamen to join Jacobin mobs in the crowded streets. “The town is one continuous scene of riot,” the British consul wrote in panic to his foreign minister in London. “The French seamen range the streets by night and by day,

armed with cutlasses and commit the most daring outrages. Genet seems ready to raise the tricolor and proclaim himself proconsul. President Washington is unable to enforce any measures in opposition.”

37

armed with cutlasses and commit the most daring outrages. Genet seems ready to raise the tricolor and proclaim himself proconsul. President Washington is unable to enforce any measures in opposition.”

37

As pro-French mobs formed on street corners demanding Washington's head, Genet sent the President an ultimatum “in the name of France” to call Congress into special session to choose between neutrality and war. Genet warned Washington that if he refused to declare war against Britain, Genet would “appeal to the people” to overthrow the government and unite with France. “I have acquired the esteem and the good wishes of all republican Americans by tightening the bonds of fraternity between them and ourselves,” Genet ranted. He predicted that Americans would “rally from all sides” to support him and “demonstrate with cries of joy . . . that the democrats of America realize perfectly that their future is ultimately bound with France.”

38

38

Infuriated by the Frenchman's behavior, John Quincy assailed Genet's “political villainy.” In a series of articles, he condemned the Frenchman's activities in America; he labeled as “piracy” and “highway robbery” the attacks on British ships by privateers sponsored by Genet. Writing under the pseudonym “Columbus,” John Quincy called Genet “the most implacable and dangerous enemy to the peace and happiness of my country.” He called Genet's conduct “obnoxious” and urged the President to demand his recall. “In a country where genuine freedom is enjoyed,” John Quincy declared, “it is unquestionably the right of every individual citizen to express without control his sentiments upon public measures and the conduct of public men. . . . The privilege ought not, however . . . to be extended to the conduct of foreign ministers.”

39

39

John Quincy's articles “attracted much attention in the principal cities of the continent and drew forth many comments,” he recalled in his memoirs

.

“It fell under the eye of Washington, then . . . anxiously considering the very same class of questions in a cabinet almost equally divided in opinion. He seems to have been impressed by the proof of Mr. Adams's powers to such an extent as to mark him out for the public service at an early opportunity.”

40

.

“It fell under the eye of Washington, then . . . anxiously considering the very same class of questions in a cabinet almost equally divided in opinion. He seems to have been impressed by the proof of Mr. Adams's powers to such an extent as to mark him out for the public service at an early opportunity.”

40

John Quincy's articles generated national and international comment, with Boston Federalists embracing himâand even naming him the city's official July 4 orator, the highest nonelective honor Bostonians conferred on one of their own each year. With his oratory, John Quincy pleased Federalists and Antifederalists alike by predicting that American liberty would soon inspire oppressed peoples in Europe to mirror the American Revolution.

In the weeks that followed, President Washington reacted fiercely to Edmond Genet's activities, demandingâand obtainingâhis recall by the French government. Washington also accepted Jefferson's resignation. To Washington's relief, a new French ambassador, Jean-Antoine-Joseph Fauchet, arrived in Philadelphia at the beginning of 1794âwith a warrant for Genet's arrest and a guillotine aboard ship to punish him for his indiscretions as French minister. Genet pleaded with the new secretary of state, Edmund Randolph, not to enforce the warrant, all but sobbing that a former Paris police chief was waiting below deck on Fauchet's ship, sharpening a blade to sever his neck. A former Virginia governor and close friend of Washington, Randolph turned to the President for guidance.

“We ought not to wish his punishment,” Washington decided generously, granting the Frenchman political asylum and the protection of the government he had tried to overthrow.

41

Fearing Fauchet's agents would kidnap him, Genet sneaked out of Philadelphia during the night and found his way to a secluded hideaway on a friend's farm in Bristol, Connecticut, where he temporarily disappeared from public view. With Genet's disappearance, the Francophile press in the East ended its provocations, and rioters all but vanished from the streets of eastern cities.

41

Fearing Fauchet's agents would kidnap him, Genet sneaked out of Philadelphia during the night and found his way to a secluded hideaway on a friend's farm in Bristol, Connecticut, where he temporarily disappeared from public view. With Genet's disappearance, the Francophile press in the East ended its provocations, and rioters all but vanished from the streets of eastern cities.

Although John Quincy's articles attacking Genet had impressed President Washington, they apparently did not please John Adams. Worried that his son was focusing less on building his law practice than writing newspaper essays without recompense, John Adams admonished John Quincy and reiterated his ambitions for his son's rise to national leadership and the presidency. “The mediocrity of fortune that you profess ought not to content you. You come into life with advantages which will disgrace

you if your success is mediocre. And if you do not rise to the head not only of your profession but of your country it will be owing to your own

Laziness, Slovenliness

and

Obstinacy

” (his italics and caps).

42

you if your success is mediocre. And if you do not rise to the head not only of your profession but of your country it will be owing to your own

Laziness, Slovenliness

and

Obstinacy

” (his italics and caps).

42

Â

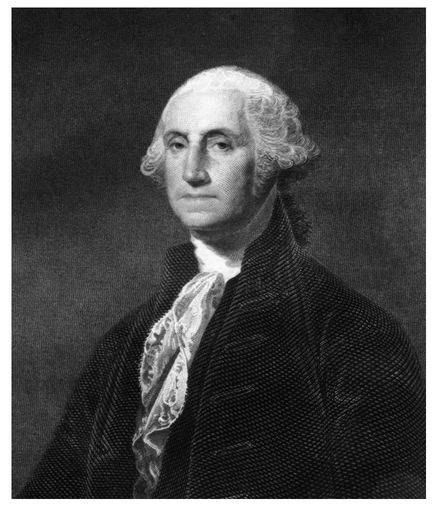

President George Washington appointed John Quincy Adams American minister to Holland and set the young man on the path to a life of public service.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Other books

Savage Range by Short, Luke;

You Are the Reason by Renae Kaye

Lord Keeper by Tarah Scott

The Neuropathology Of Zombies by Peter Cummings

Cat Found by Ingrid Lee

At Wit's End by Lawrence, A.K.

Seeker of Shadows by Nancy Gideon

Was it Good for You Too? by Naleighna Kai

Beckett's Convenient Bride by Dixie Browning

Blazing Obsession by Dai Henley