John Quincy Adams (3 page)

Authors: Harlow Unger

At John Quincy's birth, his father's reputation had spread far beyond Braintree. “The disputes [with Britain] grew,” John Quincy explained, and “agitated no household more than that in which this boy was growing up. My father, from pursuing a professional life, began to feel himself impelled more and more into the vortex of controversy. . . . My mother's temperament readily caught the rising spirit of popular enthusiasm and communicated it to me.”

8

8

A move from Braintree to Boston put John Quincy's father close to the state's most influential clientsâand at the center of popular anger over British rule. “America is on the point of bursting into flames,” Boston's

Sons of Liberty warned,

9

and on March 5, 1770, two years after John Quincy's family had settled in town, an angry mob transformed the Sons of Liberty's warning into the Boston Massacre, with British troops killing two men and wounding eight, two of whom quickly died from their injuries.

Sons of Liberty warned,

9

and on March 5, 1770, two years after John Quincy's family had settled in town, an angry mob transformed the Sons of Liberty's warning into the Boston Massacre, with British troops killing two men and wounding eight, two of whom quickly died from their injuries.

To prevent disorder from spreading, the royal governor ordered the soldiers and commanding officer arrested and charged with murder. He thwarted accusations of favoritism by naming John Quincy's father and his mother's cousin Josiah Quincyâtwo outspokenly anti-British lawyersâto defend the soldiers in an out-of-town trial before a jury of farmers, none of them Tories. Motivated in part by political ambition, Adams gambled that, win or lose, the case would show him as a man of stature who eschewed hatred in favor of the law and the right of every free Englishman to a trial by a jury of his peers. Fearing reprisals against his family, he sent his wife, who had just given birth to their second son, Charles, to the safety of their Braintree farm with their children. He need not have worried. After his brilliant summation, the jury unanimously acquitted the soldiers, saying they had legitimately defended themselves against unprovoked mob assault.

His courtroom triumph gained John Quincy's father national and international fameâand election as Boston's representative in the Massachusetts House of Representatives. The trial also ended mob protests; the troops retired, and with Boston at peace, the Adams family moved back to town, where Abigail gave birth to their third son, Thomas Boylston Adams.

Although street disorders ended for a while, new import duties provoked more smuggling, and by the end of 1773, protests against a British tea tax climaxed with a mob boarding three ships in Boston Harbor and dumping more than three hundred chests of tea, worth about $1 million, overboard. British troops returned to Boston, declared martial law, and closed the city to commerce, threatening to keep it closed until Bostonians either repaid the East India Company for the vandalized teaâor starved.

“Boston became a walled and beleaguered town,” John Quincy recounted. “Among the first fruits of war, was the expulsion of my father's family from their peaceful abode in Boston to take refuge in his and my native town of Braintree.”

10

10

Outraged by the British threat to starve the innocent with the guilty, colonial leaders elsewhere convened a Continental Congress in the fall of 1774 to respond, and after ensuring his family's safety in Braintree, John Quincy's father rode off to Philadelphia with four other Massachusetts delegates. Although the First Continental Congress ended indecisively in late October, orders arrived in the spring for British troops to crush the rebellion and “arrest the principle actors and abettors in the Congress,”

11

including John Adams. John Quincy never forgot the terror he felt when he heard of the threat to arrest his father: “My mother with her infant children, dwelt every hour of the day and of the night liable to be butchered in cold blood, or taken and carried into Boston as hostages by any foraging or marauding detachment of men.”

12

11

including John Adams. John Quincy never forgot the terror he felt when he heard of the threat to arrest his father: “My mother with her infant children, dwelt every hour of the day and of the night liable to be butchered in cold blood, or taken and carried into Boston as hostages by any foraging or marauding detachment of men.”

12

In May 1775, John Quincy's father again left for Philadelphia and a Second Continental Congress, where forty-three-year-old George Washington arrived in uniform dressed for war. At six foot three, he towered over other delegatesâespecially forty-year-old John Adams, who, even his wife Abigail conceded, was “short, thick and fat.”

13

Nonetheless, their mutual interest in farming gave Adams and Washington common ground to form a firm friendship that often included dining and attending church services together.

13

Nonetheless, their mutual interest in farming gave Adams and Washington common ground to form a firm friendship that often included dining and attending church services together.

On June 2, a letter from Dr. Joseph Warren, a close family friend of the Adamses and president of the Massachusetts Provincial Congress, urged the Continental Congress to take control of disorganized New England militiamen laying siege to Boston by appointing a commander in chief. “The sword should, in all free states, be subservient to the civil powers,” Warren argued. “We tremble at having an army (although consisting of our own countrymen) established here without a civil power to provide for and control them.”

14

14

In a more dire letter, Abigail Adams wrote to her husband of the chaos engulfing Braintree, with their home a “scene of confusionâsoldiers coming in for lodging, for breakfast, for supper, for drink, &c. &c.”

Sometimes refugees from Boston tired and frightened seek an asylum for a day or night, a weekâyou can hardly imagine how we live. . . . I wish

you were nearer to us. We know not what a day will bring forth nor what distress one hour may throw us into.

15

you were nearer to us. We know not what a day will bring forth nor what distress one hour may throw us into.

15

Â

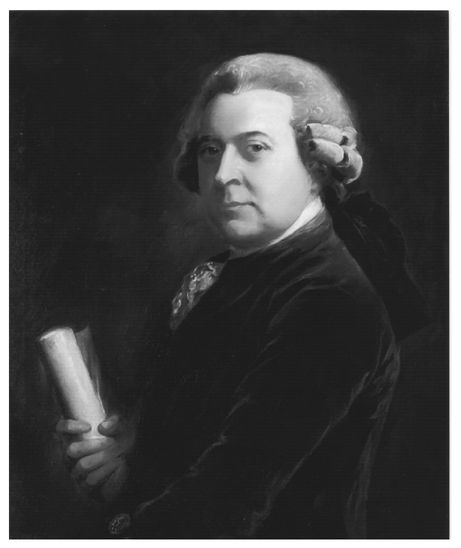

John Adams, second President of the United States and father of John Quincy Adams, the nation's sixth President. He had been a prominent lawyer before attending the first two Continental Congresses, and his

Thoughts on Government

served as the basis for constitutions in nine of the thirteen states after independence.

(AFTER A PORTRAIT BY JOHN SINGLETON COPLEY; NATIONAL PARKS SERVICE, ADAMS NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK)

Thoughts on Government

served as the basis for constitutions in nine of the thirteen states after independence.

(AFTER A PORTRAIT BY JOHN SINGLETON COPLEY; NATIONAL PARKS SERVICE, ADAMS NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK)

Visibly upset by Abigail's letter, John Adams replied by return, “Oh that I was a soldier! I will be. I am reading military books. Everybody must and will and shall be a soldier. . . . My dear Nabby and Johnny and Charley and Tommy are never out of my thoughts. God Bless, preserve and prosper them.”

16

16

A few days later, John Adams reacted to Dr. Warren's warning and asked Congress to draft patriot forces besieging Boston into a Continental Army and appoint a supreme commander. Congress agreed, and again Adams rose to speak. He had mingled discreetly with delegates from middle and southern colonies and discovered “a jealousy against a New England Army under the command of a New England General,” who, if he defeated the British, might give law to the other states.

“I had no hesitation to declare,” he responded, “that I had but one gentleman in mind for that important command, and that was a gentleman from Virginia . . . whose skill and experience as an officer, whose independent fortune, great talents, and excellent universal character, would command the approbation of all the colonies better than any other person in the Union.”

17

Two days later, Boston's John Hancock, the president of Congress, wrote to Dr. Joseph Warren, “The Congress here have appointed George Washington, Esq., General and Commander-in-Chief, of the Continental Army.”

18

As Hancock penned his inimitable signature, however, Warren already lay dead on the field of battle at Breed's Hill, on the Charlestown peninsula opposite Boston.

17

Two days later, Boston's John Hancock, the president of Congress, wrote to Dr. Joseph Warren, “The Congress here have appointed George Washington, Esq., General and Commander-in-Chief, of the Continental Army.”

18

As Hancock penned his inimitable signature, however, Warren already lay dead on the field of battle at Breed's Hill, on the Charlestown peninsula opposite Boston.

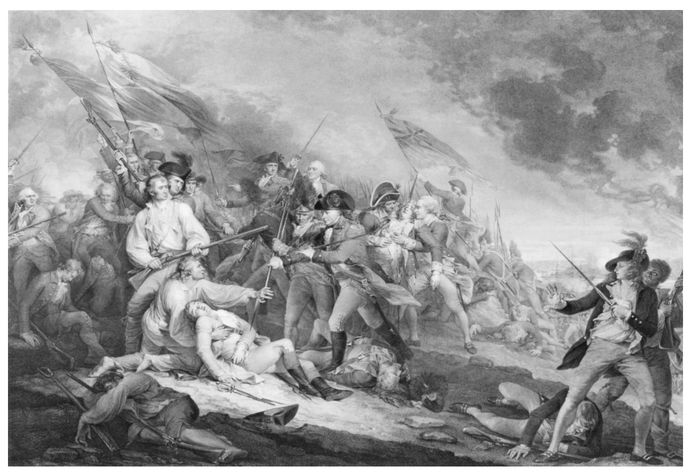

Like Boston, Charlestown sat in Boston Bay on what was nearly an island, connected to the mainland by a narrow neck. Two hills dominated the neck, Bunker's Hill, as it was then called, near the mainland, and the smaller Breed's Hill, nearer the water. Warren had gone to Bunker's Hill to warn the commander of ammunition shortages and joined the troops behind a makeshift fortification on Breed's Hill.

When she heard the first cannon blasts, Abigail Adams shuddered, then suppressed her fears of running into British soldiers and took seven-year-old John Quincy to a hilltop behind their home in Braintree, where they watched a battle unfold across the bay. By day's end, the battle had turned into a slaughter. The first British troops to land had set Charlestown aflame, while 2,400 of their comrades swarmed up the hillside like antsâonly to topple by the hundreds under a rain of American fire from above.

“The town all in flames around them,” Abigail wrote to her husband, “and the heat from the flames so intense as scarcely to be borne . . . and

the wind blowing the smoke in their faces . . . the reinforcements not able to get to them.”

19

the wind blowing the smoke in their faces . . . the reinforcements not able to get to them.”

19

Â

An 1830 map of Boston Harbor shows Quincy Bay at the bottom, with the site of President John Quincy Adams's home indicated in small print.

Seven-year-old John Quincy and his mother watched a second wave of British troops surge upward over their fallen comradesâonly to fall back again, regroup, and charge a third time, tripping over lifeless bodies, sprawling to the ground into pools of blood and torn flesh, then crawling upwards on their hands and knees until enough reached the summit to silence the few patriot arms not out of ammunition. One thousand dead

British soldiers covered the hillside; 100 dead patriots and 267 wounded lay on the hilltop. John Quincy said the battle and the carnage it left made “an impression in my mind” that haunted him the rest of his life.

British soldiers covered the hillside; 100 dead patriots and 267 wounded lay on the hilltop. John Quincy said the battle and the carnage it left made “an impression in my mind” that haunted him the rest of his life.

Â

Seven-year-old John Quincy Adams witnessed the Battle of Bunker's Hill with his mother from a distant hilltop. Nearly 270 patriots perished, including Dr. Joseph Warren, the Revolutionary War leader and the Adams family's physician, seen in the throes of death in an engraving by Gotthard von Muller, after the painting by John Trumbull.

(NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION)

(NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION)

“I saw with my own eyes the fires of Charlestown,” he exclaimed, “and heard Britannia's thunders in the battle . . . and witnessed the tears of my mother and mingled them with my own at the fall of Dr. Joseph Warren, a dear friend of my father, and a beloved physician to me.”

20

Only days before his death, Warren had devised an ingenious array of splints to save John Quincy's forefinger from amputation after the boy had suffered a bad fracture.

20

Only days before his death, Warren had devised an ingenious array of splints to save John Quincy's forefinger from amputation after the boy had suffered a bad fracture.

John Quincy watched his mother sob as she described Warren's death to her husband: “Our dear friend . . . fell gloriously fighting for his

countryâsaying better to die honorably in the field than ignominiously hang upon the gallows.”

21

countryâsaying better to die honorably in the field than ignominiously hang upon the gallows.”

21

When the last patriot lay still on Bunker's Hill and the British had ceased firing, Abigail led her frightened seven-year-old home, and together they recited the Lord's Prayer. “My mother was the daughter of a Christian clergyman,” John Quincy explained, “and therefore bred in the faith of deliberate detestation of war.”

22

Abigail made John Quincy promise to repeat the Lord's Prayer each morning before rising from his bedâa promise he kept for the rest of his life. The memory of Bunker's Hill, he said, “riveted my abhorrence of war to my soul . . . with abhorrence of tyrants and oppressors . . . [who] wage war against the rights of human nature and the liberties and rightful interests of my country.”

23

22

Abigail made John Quincy promise to repeat the Lord's Prayer each morning before rising from his bedâa promise he kept for the rest of his life. The memory of Bunker's Hill, he said, “riveted my abhorrence of war to my soul . . . with abhorrence of tyrants and oppressors . . . [who] wage war against the rights of human nature and the liberties and rightful interests of my country.”

23

Other books

A Line in the Sand by Seymour, Gerald

Warlord Metal by D Jordan Redhawk

Devil May Care by Sebastian Faulks

Prophecy by James Axler

Never Look Back by Clare Donoghue

Quietly in Their Sleep by Donna Leon

South Phoenix Rules by Jon Talton

Prentice Alvin: The Tales of Alvin Maker, Volume III by Orson Scott Card

The Dawn of Innovation by Charles R. Morris