John Quincy Adams (8 page)

Authors: Harlow Unger

On July 25, he reached Berlin, which he called “the handsomest and the most regular city I ever saw,”

2

but he criticized the king, who “treats his people like slaves.” They found conditions worse when they crossed into Poland, where, for the first time in his life, John Quincy encountered

slaves. “All the farm workers are in the most abject slavery,” he noted with disgust. “They are bought and sold like so many beasts, and are sometimes even changed for dogs or horses. Their masters have even the right of life and death over them, and if they kill one of them they are only obliged to pay a trifling fine. [The slaves] may buy [their freedom], but their masters . . . take care not to let them grow rich enough for that. If anybody buys land, he must buy all the slaves that are upon it.”

3

2

but he criticized the king, who “treats his people like slaves.” They found conditions worse when they crossed into Poland, where, for the first time in his life, John Quincy encountered

slaves. “All the farm workers are in the most abject slavery,” he noted with disgust. “They are bought and sold like so many beasts, and are sometimes even changed for dogs or horses. Their masters have even the right of life and death over them, and if they kill one of them they are only obliged to pay a trifling fine. [The slaves] may buy [their freedom], but their masters . . . take care not to let them grow rich enough for that. If anybody buys land, he must buy all the slaves that are upon it.”

3

Â

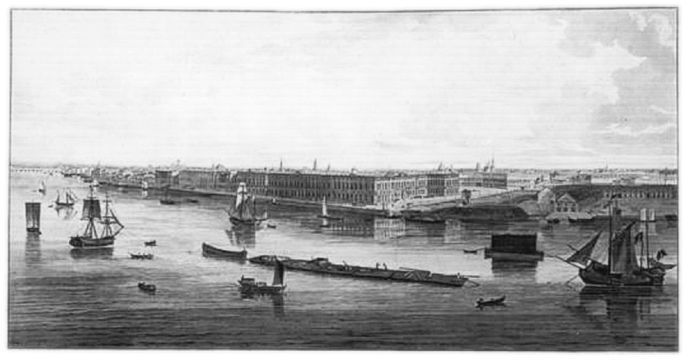

Panoramic view of St. Petersburg, where fifteen-year-old John Quincy Adams spent the winter of 1782 as secretary and translator for American minister Francis Dana. The palatial buildings in the center include the famed Winter Palace and the then new Hermitage, in which Catherine the Great housed her art collection.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

On August 27, 1781, John Quincy and Dana reached St. Petersburg and settled in the luxurious Hotel de Paris, near the Winter Palace. “The city of Petersburg,” he wrote to John Thaxter in Paris, “is the finest I ever saw. It is by far superior to Paris, both for the breadth of its streets, and the elegance of the private buildings.”

To Dana's dismay, Russian foreign ministry officials refused to receive him or even recognize his presence. His notes went unanswered, and sentries refused him entry through the palace gates. In frustration, he turned to the French chargé d'affaires for help, but Foreign Minister Comte de Vergennes at Versailles had sent instructions not to aid the Americans. The

French diplomat exuded warm words and pledged to help, but stunned Dana by suggesting that the American's reliance on a child as his secretary and interpreter might compromise his status.

French diplomat exuded warm words and pledged to help, but stunned Dana by suggesting that the American's reliance on a child as his secretary and interpreter might compromise his status.

Â

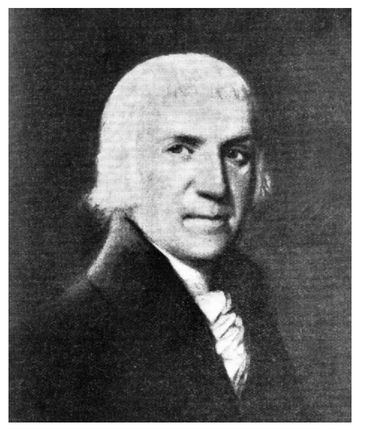

Massachusetts-born and Harvard-educated Francis Dana served at Valley Forge with George Washington before becoming an American diplomat and the first American envoy to Russia.

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

(LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

Not long thereafter, stunning news arrived of George Washington's remarkable victory at Yorktown. Although Dana was certain the American triumph would open doors at the Winter Palace, weeks passed without success. As winter's paralyzing deep freeze enveloped the Russian capital, John Quincy had nothing to do but study. Although their lodgings were warm enough, temperatures outside dropped to levels that made venturing into the fresh air foolhardy. “The thermometer at night,” John Quincy noted in early February 1782, “was 15 degrees below freezing.” It fell to twenty-five below, then twenty-eight below. “Stayed at home all day.”

4

4

By then, his diary entries had shrunk to a sentence or two, noting only the temperature and his decision to remain inside and read. Both he and Dana

were idle most of the time, with no diplomatic work or contact with Russian authorities. It was fortunate that St. Petersburg had at least one bookshop with English-language works, and both John Quincy and Dana purchased an enormous quantity. Before the end of winter, John Quincy had readâamong other thingsâall eight volumes (more than five hundred pages each) of David Hume's

History of England

, Catherine Macaulay's eight-volume

The History of England from the Accession of James I to that of the Brunswick Line,

William Robertson's three-volume

The History of the Reign of Charles V

, Robert Watson's two-volume

The History of the Reign of Philip the Second, King of Spain,

Thomas Davies's

Memoirs of the Life of David Garrick

, and the two-volume landmark work in economics by Adam Smith,

An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

. He also restudied Cicero's

Orations

and John Dryden's

Works of Virgil,

copied the poems of Dryden, Alexander Pope, and Joseph Addisonâand learned to read and write German.

were idle most of the time, with no diplomatic work or contact with Russian authorities. It was fortunate that St. Petersburg had at least one bookshop with English-language works, and both John Quincy and Dana purchased an enormous quantity. Before the end of winter, John Quincy had readâamong other thingsâall eight volumes (more than five hundred pages each) of David Hume's

History of England

, Catherine Macaulay's eight-volume

The History of England from the Accession of James I to that of the Brunswick Line,

William Robertson's three-volume

The History of the Reign of Charles V

, Robert Watson's two-volume

The History of the Reign of Philip the Second, King of Spain,

Thomas Davies's

Memoirs of the Life of David Garrick

, and the two-volume landmark work in economics by Adam Smith,

An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

. He also restudied Cicero's

Orations

and John Dryden's

Works of Virgil,

copied the poems of Dryden, Alexander Pope, and Joseph Addisonâand learned to read and write German.

“I don't perceive that you take pains enough with your hand writing,” his father growled in response. “When the habit is got, it is easier to write well than ill, but this habit is only to be acquired in early life.” Adams ended his letter more warmly, however: “God bless my dear son and preserve his health and his manners from the numberless dangers that surround us wherever we go in this world. So prays your affectionate father, J. Adams.”

5

5

Crestfallen at his father's response to his studies, John Quincy did not reply for a month, and when he did, he wrote in French to make it difficult for the elder Adams to read. Adams answered acerbically, “It is a mortification to me to find that you write better in a foreign language than in your mother tongue.” Adams was, however, worried about his sonâan adolescent, all but alone in a foreign land, with no companions but a middle-aged man and a pile of books.

“Do you find any company?” John Adams wrote. “Have you formed any acquaintances of your own countrymen? There are none I suppose. Of Englishmen you should beware. . . . My dear boy, above all preserve your innocence.”

6

He grew more anxious as the winter progressed without John Quincy's gaining any substantial diplomatic experience. “I am . . . very uneasy on your account,” he wrote in mid-May. “I want you with me. . . . I

want you to pursue your studies at Leyden. . . . Your studies I doubt not you pursue, because I know you to be a studious youth, but above all preserve a sacred regard to your own honor and reputation. Your morals are worth all the sciences.”

7

6

He grew more anxious as the winter progressed without John Quincy's gaining any substantial diplomatic experience. “I am . . . very uneasy on your account,” he wrote in mid-May. “I want you with me. . . . I

want you to pursue your studies at Leyden. . . . Your studies I doubt not you pursue, because I know you to be a studious youth, but above all preserve a sacred regard to your own honor and reputation. Your morals are worth all the sciences.”

7

John Quincy finally admitted to himselfâand to his fatherâ“I have not made many acquaintances here.” Although he had “as much as I want to read,” he longed for companions his own age. In addition, the crushing poverty, deprivation, and lack of freedom in Russian lifeâand the oppressive slavery he witnessedâleft him depressed. “Everyone that is not a noble,” he lamented, “is a slave.”

8

8

His father responded by urging John Quincy to return to Holland. Adams had succeeded in winning Dutch recognition of American independence and had moved to The Hague as American minister plenipotentiary.

Although eager to rejoin his father, John Quincy was enjoying his independence and took a long, circuitous route back to Holland through Scandinavia and Germany. After three weeks exploring Finland (then a part of Sweden), he reached Stockholm, and ignoring his father's exhortations on the importance of preserving his innocence, John Quincy Adams plunged into Swedish life for nearly six rapture-filled weeks.

“I believe there is no country in Europe,” he exulted, “where the people are more hospitable and affable to strangers or more hospitable . . . than the Swedes. In every town, however small it may be, they have these assemblies [dances] . . . to pass away agreeably the long winter evenings. . . . There, one may dance country dances, minuets or play cards, just as it pleases you, and everybody is extremely polite to strangers.” Years later, he recalled, that “the beauties of the women . . . could not be concealed. . . . The Swedish women were as modest as they were amiable and beautiful. To me it was truly the âland of lovely dames,' and to this hour I have not forgotten the palpitations of heart which some of them cost me.”

9

9

While he was sampling Sweden's wine and women, his parents grew frantic. “I hope our dear son abroad,” Abigail fretted to John, “will not imbibe any sentiments or principles which will not be agreeable to the laws, the government and religion of our own country. He has been less

under your eye than I could wish. . . . If he does not return this winter, I wish you to remind him that he has forgotten to use his pen to his friends upon this side of the water.”

10

John Adams feigned nonchalance in replying to Abigail but sent inquiries to French consuls in Germany and Scandinavia about his son's whereabouts.

under your eye than I could wish. . . . If he does not return this winter, I wish you to remind him that he has forgotten to use his pen to his friends upon this side of the water.”

10

John Adams feigned nonchalance in replying to Abigail but sent inquiries to French consuls in Germany and Scandinavia about his son's whereabouts.

John Quincy had reached Göteborg on the west coast of Sweden with every intention of remaining, when the French consul reported his father's anxieties and set the boy scrambling to make travel arrangements to Holland. He took a final fling at a masquerade ball where “the men dressed as sailors and the women [as] country girls. . . . I stayed there till about 4 o'clock this morning. When I returned to my lodgings, I threw myself upon the bed and slept till about 7 o'clock, then packed my trunks and set away.”

11

11

In the weeks that followed, John Quincy traveled to Copenhagen, Hamburg, and Bremen, finally rejoining his father in The Hague on July 22ânoticeably more mature than when he had left.

“John is every thing you could wish,” Adams explained to Abigail without revealing the obvious changes in his personality or probable causes. “Wholly devoted to his studies, he has made a progress which gives me entire satisfaction. . . . He is grown a man in understanding and stature as well. . . . I shall take him with me to Paris and shall make much of his company.”

12

Even Abigail was impressed after reading John Quincy's first letter to her upon his return to Holland. “The account of your northern journey,” she conceded, “would do credit to an older pen.”

13

12

Even Abigail was impressed after reading John Quincy's first letter to her upon his return to Holland. “The account of your northern journey,” she conceded, “would do credit to an older pen.”

13

Adams was more than delighted with his son, and early in August, the two left The Hague for Paris, where John Adams joined Benjamin Franklin and John Jay in negotiating a peace treaty with Englandâand elated John Quincy by recruiting him as a secretary to edit and transcribe documents. John Adams now accepted his precocious sixteen-year-old son as a man, a friend, and a pleasant, sophisticated companion, not only at concerts, the opera, and museums but at luncheons, dinners, and other functions with some of Europe's most distinguished figures. They, in turn, also accepted the young man as an equal. “Dined at . . . the Dutch ambassador

with a great deal of company,” John Quincy reported in his diary in mid-August 1783. “Dined at the Duke de la Vauguyon . . . the French ambassador at the Hague . . . the Baron de la Houze . . . the minister of France at the court of Denmark.”

14

With each encounter, he listened carefully, gradually learning the language of diplomacy in which spoken words seldom matched their literal meanings. An “interesting concept” often meant “unacceptable,” while a “different approach” could well mean war.

with a great deal of company,” John Quincy reported in his diary in mid-August 1783. “Dined at the Duke de la Vauguyon . . . the French ambassador at the Hague . . . the Baron de la Houze . . . the minister of France at the court of Denmark.”

14

With each encounter, he listened carefully, gradually learning the language of diplomacy in which spoken words seldom matched their literal meanings. An “interesting concept” often meant “unacceptable,” while a “different approach” could well mean war.

With France a center of scientific advances, John Quincy also witnessed astounding new processes and inventions and developed a deep interest in science. “My Lord Ancram,” he recounted in his diary, “has undertaken to teach people born deaf and dumb not only to converse . . . fluently but also to read and write.” Another entry described his having witnessed “the first public experiment . . . of the flying globe.”

A Mr. Montgolfier has discovered that if one fills a ball with inflammable air much lighter than common air, the ball of itself will go up to an immense height. It was . . . 14 foot in diameter . . . placed in the Champs de Mars.

g

At 5 o'clock, two great guns fired from the Ãcole Militaire. . . . It rose at once, for some time perpendicular and then slanted. . . . If it succeeds it may become very useful to mankind.

15

g

At 5 o'clock, two great guns fired from the Ãcole Militaire. . . . It rose at once, for some time perpendicular and then slanted. . . . If it succeeds it may become very useful to mankind.

15

The launch of the first balloon set off a mania in France, with Joseph de Montgolfier and his brother Ãtienne sending balloons into the atmosphere in Versailles and elsewhere. “The enthusiasm of the people of Paris for the flying globes is very great,” John Quincy noted with excitement. “Several propositions have been made from persons who, to enjoy the honor of having been the first travelers through the air, are willing to go up in them and run risks of breaking their necks.”

16

16

Other books

LUCI (The Naughty Ones Book 2) by Kristina Weaver

Dirty Beautiful Rich Part One by Devon, Eva

Scarlet Dusk by Megan J. Parker

Victory Square by Olen Steinhauer

Meet Me at the Beach (Seashell Bay) by V. K. Sykes

A Time to Mend by Sally John

Galaxies Like Grains of Sand by Brian W Aldiss

Take Me by Stevens, Shelli

Luminescence (Luminescence Trilogy) by Weil, J.L.

The Lovers by Vendela Vida