Joyland (9 page)

Tammy tapped the glass with her finger. Its hollow

tink.

The firefly fell backward, then buzzed up again.

Bees: kaleidoscopic vision

, she remembered. The words appeared in her brain as if on flashcards.

Bees see simultaneously from several different angles . . . Almost,

she told herself,

like seeing everything at once.

Tammy wondered if the same held true for fireflies. She watched its rear end glint once more. Then she unscrewed the lid and let the bug flit away, a dark speck on the dark, until it had reached a safe distance again.

When the first fireworks hit the sky, Samantha’s hair slipped from Tammy’s hand in a half-finished French braid. With the sudden flash of aqua light, Sam reared forward. Coloured dots

Plinko

-ed down the night. Grey-white streaked the sky like a gone-to-seed dandelion.

“Awright!” Samantha said when the bang travelled the distance and broke.

Far back, Shelly Pegg sat on a lawn chair, little sister in her lap, another in her mother’s. Shelly leaned against Mrs. Pegg’s shoulder in a way that made Tammy suddenly jealous. When the firework burst, the one lumpy figure they made in the night clapped with the enthusiasm of a crowd.

Rodney put two fingers in his mouth and released a long shriek of a whistle.

Bits of fire and ash broke apart from their compact shells, where gunpowder and chemicals — dioxides, Chris had told Tammy — pressed tight, waiting to distribute this formation of colour. As flecks of orange rained down, lighting upturned faces, Tammy glanced over to where Rodney was sitting. She tried to imagine what he looked like underneath his clothes, to see him the way Sam did. He gave no indication of being watched, and Tammy looked away. In front of her, Samantha was absently unweaving her half-braided head. Behind her, Tammy could feel Mrs. Sturges and Mr. Riley pressing closer together. She knew they were holding hands.

Between the inevitable smashing and trickling down, there was a sense of hovering, gapping. Suddenly, Tammy’s throat felt stretched and raw. It was from standing too close to the barbecue earlier, breathing in the lighter-fluid fumes and the air streaked by charcoal. When she ran her hand across her eyes, she was sure it was because the fireworks had a double impact, stretched out as they were, reflected in the water. It was because they were so bright.

She wondered what her parents were doing right now, whether they had joined the crowd downtown, or were watching on the local cable channel, or were just creeping around in the dark of the house — which was how Tammy always imagined the house after she had left it.

Where was Chris?

she wondered.

PLAYER 1

Chris shot the mushrooms. He killed the spider for 600 points before it could brush against him. He loved the crueller, less-apparent elements of such games, the fact that so often, touch could kill. Zapping the centipede on the screen before him, Chris revelled in its breaking — down and down into smaller and smaller bits, each of them alive, inching its way downward.

“Could you hit a few more mushrooms?” J.P. oozed sarcasm, completely bored by Chris’s burgeoning score. He leaned back against another machine, flexed the brim of his ball cap. Circus Berzerk was a far cry from Joyland. The plaza offered the comforts of air conditioning, but little else.

“Technically . . . they’re toadstools.” Chris jerked his player away from a falling flea. At a certain point, shooting became a natural extension of breathing, as though Chris wasn’t playing the machine but simply existing in it. The boards passed from green and red to pink and blue to orange and yellow, his man moving to and fro in a rainstorm of colour.

“Jesus.” J.P. snorted. “I thought you wanted to go to Doyle’s. Would you just get yourself killed already?”

And so it ended; there was little choice for someone like Chris. High scores were lost to the whims of others. The game could go on indefinitely — infinitely, if he let it.

Below Chris, corroded green metal opened to flashes of grey: moving, shape-shifting water. The old railroad bridge was still in use, though Chris could not fathom how. Even a few years ago there had been more gaps than bridge. He stepped carefully. J.P. was doing a play-by-play sportscast of the entire crash derby though if Chris had had any interest he would have gone himself that morning to watch. He pussyfooted one running shoe in front of the other, edging alongside a crater. With shorter legs than J.P.’s, the holes seemed to open wider beneath Chris every time he glanced down. He squashed the fear with a laugh — the briefest, most private tactic available for convincing himself he could get used to this feeling, as easily as any other annoyance. Camp pranks had once induced the same queasiness: flashlights held to illuminate the face from below, casting up a ghoulish glow, lengthening the shadows of the eyes and emphasizing the sulphurous yellow tone of human skin.

Through the hole, the water thrashed. It ran fast for such a small river, as if it could compensate for its narrowness with its force. In less than a minute they would be on the other side. Chris could see the row of houses already. Shingles stood out from the trees on the riverbank like blackhead zits. One among them, he guessed, would be Doyle’s.

The boys approached from the back, unable to tell whose house was whose. The yards pressed together without fences, only red cedars or unkempt raspberry bushes lining the property. In all likelihood, kids bikes lay half in one yard and half in their neighbours’. Toys — plastic shovels and naked Barbies — were thrown here and there, half-sunk in mud. A car’s viscera lay out on a picnic table. The loving owner had wandered off and left it for the afternoon, mid-surgery. Willow whips from the trees tangled Chris’s feet as he and J.P. climbed the bank, trekking away from the railroad tracks. They headed around front, where the numbers would help them determine which house held the thing they sought.

It was no different than its neighbours: a two-storey farmhouse holding its ground in the middle of town. The entire facade was nailed over with Insulbrick. The step up to the porch was an unsteady mason block, the porch barely wide enough to accommodate Chris and J.P. A much larger verandah hugged the entire side of the house. Chris wondered if they should try around there, but J.P. had already rapped on the metal frame of the screen door.

Chris turned to him. “Are you sure . . . ?”

The door nearly broadsided Chris as it swung open. He fell backward off the porch and landed on his ass in the grass.

The man in the open doorway slouched, shirtless. He looked to be about twenty-five. Or forty-five. Chris couldn’t tell. Looking down at Chris in the grass, the guy gave a high-pitched titter — a sound young enough to have come from a fourteen-year-old, though the face it snaked out of had hard, thin lips and harder thinner eyes above them. One hand grasped at the low waist of his jeans, as if he had just pulled them on before deciding to open the door. A trail of black stitches ran down the centre of his stomach toward his groin. The pink head twisted away as the guy jerked his fly up.

Averting his eyes, Chris scrambled to his feet.

“What do you want, man?” His gaze drifted from Chris to J.P. without seeming to focus on either one of them. The guy leaned against the door, and J.P. jumped backward off the porch as the screen swung open farther under the weight.

J.P. shot Chris a quick glance. “Well, we heard . . .”

The guy in the doorway — obviously Doyle — began to laugh.

“Aw shit,” he said, pulling his hand through shoulder-length liver-brown hair. He buzzed his lips in an abrupt, juicy fart. “You crack me up, kid. What are you, like, twelve? Whad’you and your

girl-

friend come for?” Doyle shot out suggestions. The names dribbled down at Chris — tiny taboo nuggets of vocabulary.

“Awwwww, come on,” Doyle groaned, “don’t look at me like that. You’re too young to be a narc.”

J.P. answered, his voice dropping an octave, his chest instantly convex, bursting with authority. “Just booze, man.”

Doyle offered them weed instead.

Chris shook his head. The offer might have been more tempting had it come from someone capable of holding himself upright.

“Fuck. Ing. Hell,” Doyle said, each syllable a sentence, his brown head doing a slow, annoyed dance. He leaned against the door, which forced it wide. “Gonna have to wait while I go get it. C’mon in.”

J.P. went first and Chris followed, ducking past Doyle. He reeked of smoke.

“I was just in the middle of something,” Doyle muttered holding up a finger. He lurched past them into the living room. J.P. and Chris stood politely in the hall, as if they were visiting a distant relative. Faded Mom-style yellow wallpaper with flowers plastered the musty hall. Overhead, a stained glass lampshade cast bright-coloured triangles into a spiderwebbed corner. Through the doorway, at the far end of the living room, Doyle’s back was to them. A white flannel sheet with wide pink stripes on one end flapped as he unfolded it. Chris looked carefully at his feet as Doyle twisted around.

Suddenly Doyle seemed in less of a hurry. He began to offer advice on every kind of alcohol and how it would “make your frickin’ head spin . . . like a twelve-year-old girl chugging wine at a wedding.” Interwoven with his personal escapades, his expertise was wasted; the stories never reached conclusion, twice sidetracked by who had been present before he could tell the boys what had been consumed or what effects it had. After about forty minutes, he stood up as if he had just remembered why the boys had come.

“How’d you hear about me anyway?” he asked, snagging his keys from the table. Chris and J.P. exchanged worried glances, as though Doyle might back out if they gave the wrong answer.

“My brother, Marc Breton.”

At seventeen, Marc Breton was all shaved head, hulking shoulders, the rest of him hambone and hair, skin corrugated with zits. He was the kind of guy whose retort to any put-down was still “I know you are, but what am I?” not out of some kind of mental defect, but out of lack of necessity to find a new comeback, pipes more honed than brain. The dumbfounding irony, Chris had discovered, was that Marc was an honour student, squeaking in at 80%. On the floor of his bedroom his yearbook lay open to the honour roll page — constantly, as if Marc were also trying to convince himself — and Chris had seen it when he and J.P. snuck in there to play the Atari.

“Aw shit.” Doyle spread one hand on the glass top-portion of the screen door. “He’s practically old enough to buy for you. I don’t see why he couldn’t do it.” He shook his head and went outside, leaving a sweaty handprint on the door where he’d been. He hadn’t bothered to put on a shirt.

On the other side of the window he swung up into his pickup and backed it half-down the pebble driveway and half-across the yard.

“You’d think he wouldn’t drive when he’s so stoned,” J.P. laughed.

Chris poked him in the ribs and nodded to the couch at the far end of the room, where the white flannel sheet covered a human shape. One that hadn’t moved, he’d noted, since Doyle had covered it an hour ago.

LEVEL 5:

COMBAT

PLAYER 1

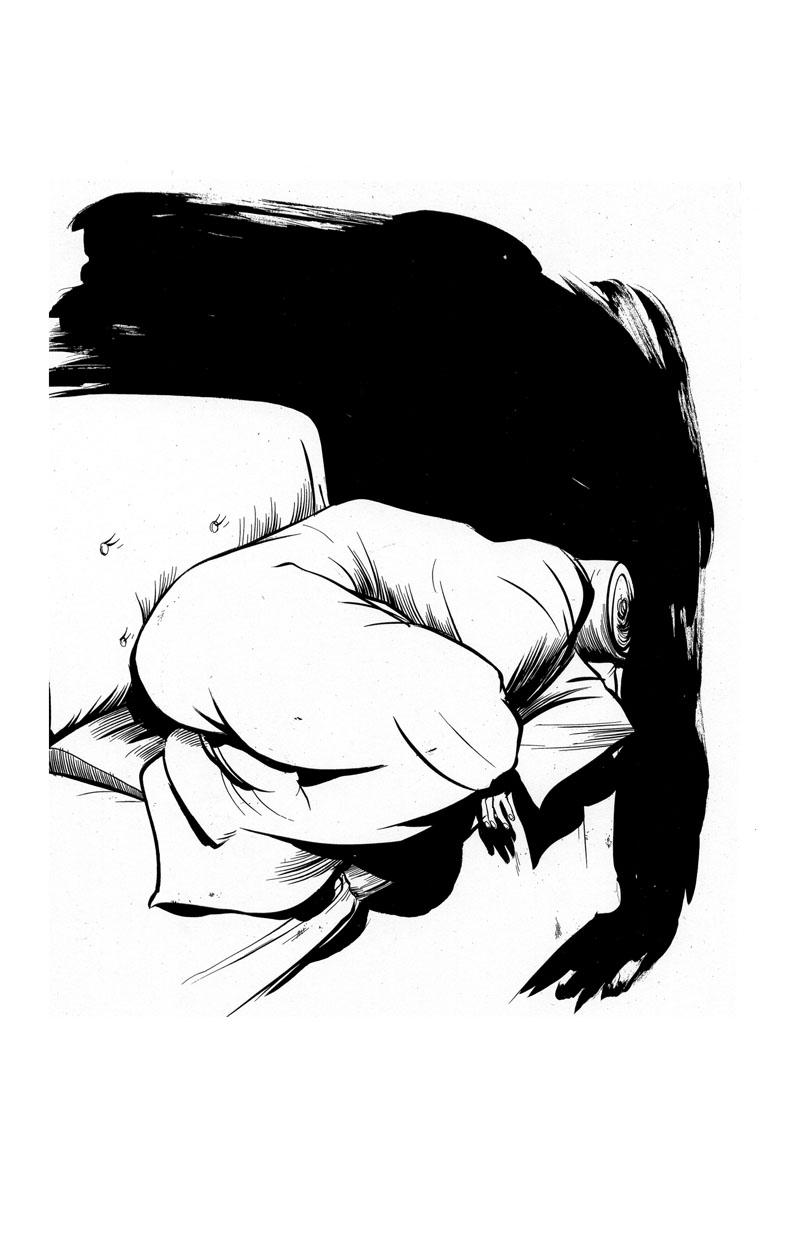

J.P. pulled the sheet all the way off her, exposing the oversize Mickey Mouse T-shirt she wore. A pair of pink underpants were visible through the well-loved white cotton shirt. A few small bruises dotted her legs and ankles. Strands of drool hung between her teeth and the pillow, colourless as fishing wire. She didn’t move.

Chris and J.P. could only guess that the girl was sixteen or seventeen. Her skin was like a boiled egg. She was smeary-eyed, black eyeliner Halloweening beneath her closed lids. She had baby-fat cheeks. Under Mickey’s smiling face her breasts seemed larger than those of the girls they knew. These were their only clues. They didn’t know her. All of this they determined quickly and without speaking. Her body was bent half-sideways and half face-down. They couldn’t tell if she had collapsed there or been thrown.

“Touch her,” J.P. said, his chest rising and falling quickly under his T-shirt.

“You do it.”

J.P. didn’t move.

“You

do it,” Chris said again.

J.P. stared back at him.

Tentatively, Chris reached out. The distance between hand and girl became immense as the two boys watched its journey. Chris made contact, brushing the bangs back from her forehead.