Languages In the World (42 page)

Read Languages In the World Online

Authors: Julie Tetel Andresen,Phillip M. Carter

- Greenberg, Joseph (1963)

The Languages of Africa

. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. - Greenberg, Joseph (1987)

Language in the Americas

. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. - Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003)

The Dravidian Languages

. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. - Ladefoged, Peter and Ian Maddieson (1996)

The Sounds of the World's Languages

. Oxford: Blackwell. - Osborne, Milton (1975)

River Road to China: The Mekong River Expedition 1866â1873

. New York: Liveright.

Postcolonial Complications

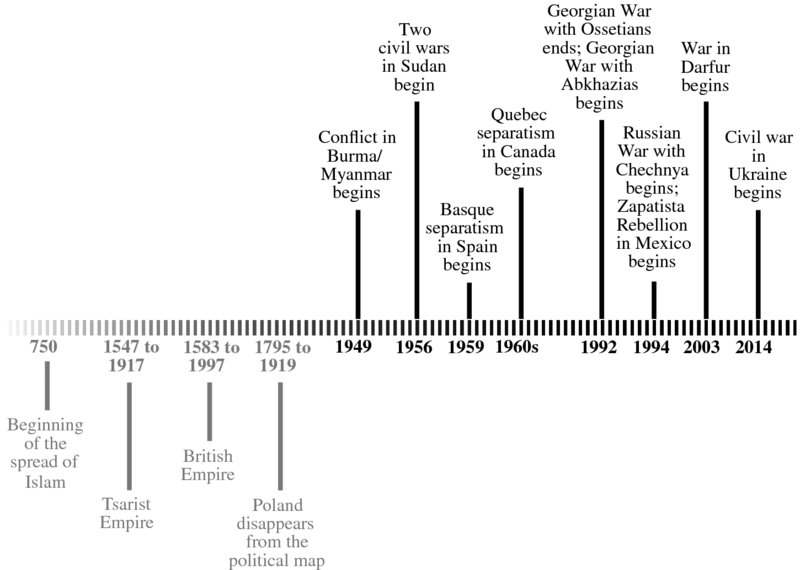

Violent Outcomes

In the Indian Ocean off the south coast of India is the island nation of Sri Lanka. The majority population is the Sinhalese, an ethnogroup who tend to be Buddhists and who speak Sinhala, an Indo-European language. They share the island with the

minority Tamils, who tend to be Hindu. Their language, Tamil, is Dravidian. In the 1980s, the people of Sri Lanka began to suffer the experience of terrorist bombings in their capital city, Colombo, and surrounding countryside, perpetrated by Tamil Tiger separatists who wanted their own state. Earlier in that decade, one Tamil Tiger, Shankar Rajee (pseudonym), on a trip to London met up with Palestinian militants, traveled with them to Beirut, and imported from the Palestinian Liberation Organization the practice of terrorist bombings. In return, here is what Rajee

exported

to the Middle East: the wearable detonation device known as the suicide belt, suicide bombing itself, the use of women in suicide attacks, and the idea of tying together terrorists and financiers into an international network of militant uprisings (Meadows 2010).

What could have been the impetus behind Rajee's desperate need to create the techniques of modern terrorism? The answer is: issues surrounding language and its social-psychological cousin, religion, that swirled into the vacuum created when the British colonialists left Ceylon in 1948.

1

Suddenly the island became an independent nation and eventually renamed itself The Republic of Sri Lanka. One of the seemingly simple, natural, and yet most disastrous moves the new government made was the passage of the Sinhala Only Act in 1956,

2

which ended the status of English as the official language and barred Tamil from the schools and government institutions. Overnight, more than a million Tamils became officially illiterate, and all of them were now at a severe disadvantage in obtaining jobs in the civil service. Violence broke out in Tamil communities, which in turn provoked a Sinhalese backlash.

Over the next 15 years, more language laws and other pro-Sinhalese reforms were enacted, and government troops were regularly deployed in agitated Tamil communities. By the 1970s, interest in a separate Tamil nation evolved into a bona fide separatist movement with militant leanings. In 1975, the group Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (âhomeland') was formed to fight for Tamil freedom in Sri Lanka. The group came to be known as the Tamil Tigers, and their violence eventually escalated into outright terrorism, which continued nearly unabated for the next two decades. Finally, in 2002, the war-fatigued nation decided upon a ceasefire agreement between the Tamil Tigers and the Sinhalese-led government. The issue of Tamil separatism came to an end.

The Tamils are one of the sad epilogues to the intertwined stories of the eighteenth-century nation-state and post-Columbian European colonialism. When Europeans left their colonies during the twentieth century, interethnic conflicts not in play prior to the colonial era often split along linguistic lines as former colonies struggled to establish themselves as nation-states. The logic used to construct the state became the same logic used to challenge it, and separatist movements began to arise all around the world, always splitting along linguistic lines. They continue to do so, because the one nation, one language ideology gives any ethnogroup the sense of a right to their own nation, to their own political border. Among the many things that move, then, in these postcolonial times are national borders, as do money and weapons, and with them, people. When money and weapons are in the hands of a militant minority ethnogroup, guerilla and/or terrorist tactics become the order of the day, as we saw for Sri Lanka. When they are in the hands of a militant majority ethnogroup and/or recognized government, an unfortunate trend of mass murder can be traced around the world.

The term

final solution

was used by the Nazis during World War II to refer to the eradication of the Jews from Nazi Germany either by expulsion or by extermination. During the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s, the term

ethnic cleansing

entered international discourse. Unfortunately, mass murders have not been confined to Nazi Germany and the former Yugoslavia. The International Criminal Court in The Hague can and does prosecute individuals for genocide and crimes against humanity.

In this chapter, we review postcolonial separatist movements around the world, all with profiles of violence and all tethered to issues of language.

In 1989, the military dictatorship in power in the Southeast Asian country then known as Burma established a language committee charged with regularizing the spelling of Burmese place names in English. The committee's primary work was to replace or modify the often haphazard spellings given to Burmese cities by the British authorities in the nineteenth-century colonial period, bringing those English spellings closer in line with actual Burmese pronunciations. Accordingly, the English name for the capital Rangoon was changed to Yangon. The committee finished its work by recommending one final change: the renaming of the country from Burma to Myanmar. The diverse ethnolinguistic minority groups in the country reacted with anger, and the event became another moment of volatility in what is the world's longest running armed geopolitical conflict, now in its seventh decade.

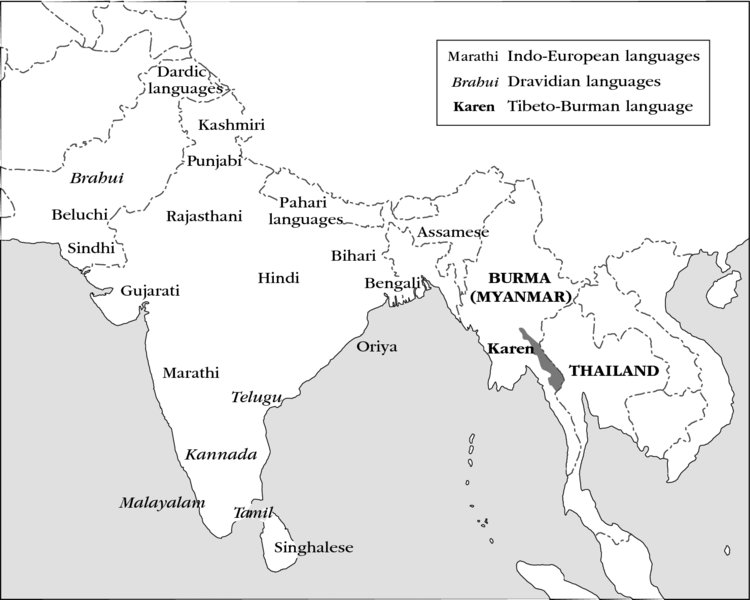

Burmese is the language spoken by the Burmans, the largest ethnic group in the country. Like many languages of Southeast Asia (see

Map 9.1

), Burmese marks strict lexical and grammatical distinctions between registers, which are styles of language used for specific purposes. It is therefore not unusual that in Burmese, two names for the country exist:

Myanma

, used in the written literary register, and

Bama

, used in the colloquial spoken register. The two names for the country have existed alongside one another for several centuries. The government's language committee argued that

Myanma

was the official name of the country in written Burmese, and therefore recommended the English name Myanmar.

3

The military dictatorship, ever suspicious of the colloquial varieties of Burmese in which

Bama

was the preferred country name, agreed. For their part, ethnic minority groups, which number more than 100 in Burma, argued that both terms were ultimately of Burmese origin and were therefore exclusionary to other language groups, and they were therefore opposed.

Map 9.1

Languages of South Asia (Dravidian languages italicized), Tibeto-Burman language bolded.

Among the most vocal opponents of the name change were an ethnogroup known as the Karens. In reality,

Karen

is a cover term for a variety of loosely related ethnic groups numbering more than four million in Burma, nine million in the region. The Karen peoples speak a number of related languages, sometimes referred to collectively as

the Karen languages

, which include Pa'O, Red Karen (Karenni), and S'gaw Karen. Though linguists agree that Karen languages are part of the Tibeto-Burman branch of Sino-Tibetan, there is not yet agreement about whether the so-called Karen languages form their own subbranch. The fact that the Karen languages are not

mutually intelligible has contributed to the underestimation of the Karen population within Burma. From the perspective of the Karen people, this underestimation contributes to their marginalization within Burmese society.

The Karens have been engaged in continuous armed conflict with the Burmans since 1949. The nature of the violence, however, cannot be reduced to Karen versus Burman, Karenni language versus Burmese language, or other such posings. The violence is instead triangulated against two more sets of related conditions: the nature of colonial intervention by the British from 1824 to 1948, and the postcolonial conditions established by the hasty British exit from the region.

In the midnineteenth century, the British Empire was at a high tide with colonies stretching from Hong Kong to Bombay. By midcentury, the fertile Irrawaddy Delta in Southeast Asia was still unclaimed by Europeans, and the British wanted it for rice production. They had already set up colonies in the interior of Burma, where they controlled the production of timber, oil wells, and mines. In 1852, they also seized control of the Irrawaddy. The draining of the delta for paddy land sent some people out of the region. Others, who wanted to work the paddies, came into the region. Burma was being transformed from the outside, and people began to scatter, disrupting long-term settlement patterns.

In the midst of this movement, colonial administrators began to play favorites with local groups, the two factors leading to British favoritism being willingness to convert to Christianity and willingness to learn English. In British Burma, it was the Karens, who already felt dominated by the Burmans, who collaborated most closely with the British. The British encouraged Karen groups to convert to Christianity, and many did. The Burmans, who felt marginalized, displaced, and exploited by the British, accused the Karens of sympathizing with Imperialists. The Burman and Karen groups were already at odds, and the preconditions for postcolonial violence were thus already in place during the colonial era.

Throughout the 100-year period of British rule, the Karens developed a keen sense of national consciousness, led at first by those who converted to Christianity. Language was an important theme in Karen nationalism, and the first Karen-language newspaper was printed in 1841. By 1928, with the British still in power, calls were issued for a state uniting the various Karen-speaking groups. In 1942, when the Japanese occupied British Burma as a part of World War II, the Burmans sided with the Japanese, while the Karens sided immediately with the British.

When the British left the region in 1948, the colonial structure immediately collapsed, and the Karens lost their ties to power. While many other ethnic groups agreed to join the independent Burma that emerged in the postcolonial period, the Karens disagreed, instead forming the Karen National Union. They took up arms and for a time even took control of large parts of the country, although eventually their control waned, and they were relegated further and further to the border with Thailand. By the 1990s, the Burman government had labeled the Karens

terrorists

, and some Karen groups did in fact take up guerilla tactics as they watched their influence wane. Others, as many as 100,000, crossed the border to seek refuge in Thailand, thus illustrating a common story for many ethnogroups in the postcolonial era: violence begets emigration.

Today, the Karen question in Burma is still unanswered, and Burma is one of the most militarized countries in the world. The Karen National Union remains suspicious of the central government, whom they perceive as wanting to Burmanize ethnic minority groups. Therefore, the maintenance of Karen ethnic identity is seen as a strategy for ongoing self-government. Language is of course everywhere at issue and at stake. While the Burmese language is the medium of instruction in most schools, the Karens advocate that their languages should be the medium of instruction in Karen-majority areas of the country, an issue we saw in Chapter 6 and the curricular status of Tibetan in Western and the Autonomous Region of Tibet.

The history of violence in Burma over the past seven decades sadly shows that one effect of colonialism in the postcolonial era is often violence and that this violence causes people to move, thereby dislocating and dispersing ethnic groups and their languages. This history also highlights the role of language in ethnic identity. For many ethnogroups, certainly the Karens, language and ethnic identity are worth fighting for. Conflict over the country's name â Burma or Myanmar â is not superficial political wrangling among differing political parties. Rather, it is deeply symbolic of the larger tensions at play involving language, ethnic identity, and national sovereignty in the postcolonial era.