Languages In the World (45 page)

Read Languages In the World Online

Authors: Julie Tetel Andresen,Phillip M. Carter

In Mexico on New Year's Day, 1994, 3000 members of the newly formed Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN)

10

descended from the jungles in the southern state of Chiapas

11

onto the streets of San Cristóbal de las Casas, an important Spanish colonial town. Dressed in black vests and brandishing a mix of ancient weapons and modern assault rifles, they stormed the town hall of San Cristóbal, burning land deeds, and eventually seizing control of the town, along with five other municipalities in the state. The Mexican government promptly issued a military counteroffensive, and intense fighting ensued for 11 consecutive days.

Between 145 and 1000 people were killed in the rebellion, depending on which side you ask. Although an exact death toll is unknown, what is clear is that the Zapatista Uprising, as the 1994 event in Chiapas has since been named, was successful in disrupting the status quo. First, it sparked a wave of protest and rebellion in Mexico that resulted in greater autonomy for indigenous groups. It also happened to disrupt the Mexican political system, precisely as the federal government was poised to implement policies designed to thrust Mexico â its indigenous communities and all â fully into the global economy. Seeing the writing on the policy wall, the Zapatista Uprising was designed to push back against the people, forms of government, epistemological frameworks, languages, and other forces of assimilation pulling southern Mexico further into the modern, postcolonial nation-state.

For seven consecutive decades beginning in the early twentieth century, Mexico was ruled by a single political party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party, or PRI, as it is known in Mexico. In Chiapas,

campesinos

âfarmers' and peasants, usually indigenous Maya, and speakers of Tzeltal and Tzotzil, were long forced by elite land owners, usually Spanish-speaking

mestizos

, to cast ballots for PRI candidates in national elections. Locally, PRI influence was evident throughout Chiapas, where they kept a stranglehold on local media, schools, and civic organizations. Spanish was the language of the nation-state, and it was likewise the language of the political infrastructure in Chiapas.

In response to these conditions, the Zapatista Army began to take shape in the 1980s. In the beginning, the movement comprised mostly nonindigenous

mestizos

interested in advocating for land reforms, which were guaranteed in the Mexican Constitution of 1917 but mostly ignored by the PRI. Over time and with the help of the Roman Catholic Church, which was also at odds with the PRI, they began organizing in indigenous communities, helping locals learn how to speak up for their own interests, and speak out against the abuses of the nonindigenous political machinery. As the movement gained momentum, the state â led by the PRI â responded with tactics of fear and intimidation in Maya communities. The communities pressed back, as indigenous men joined the Zapatista guerillas in the jungles of Chiapas, this time ready to take up arms.

As the movement became an army, a non-Maya, Spanish-speaking

mestizo

man known to the world by his nom de guerre

Subcomandante Marcos

emerged as the figurehead for the EZLN. Rumored to be a university professor, Marcos provided the Zapatistas with the anticapitalist energy and focus on social and economic

justice that provided the ideological basis for the uprising of 1994, which, in the Zapatista view, was considered war on Mexico. Marcos planned the rebellion to take place on the eve of the start of NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement, an accord that created the world's largest trade bloc between Canada, Mexico, and the United States. The signing of NAFTA happened also to be a signature policy issue for the PRI. For the Zapatistas, however, NAFTA was considered a death sentence, as poor farmers would no longer be able to compete with the commercial farms in the United States. Although NAFTA did move forward, the uprising of 1994 took its toll on the Mexican government. The Zapatistas managed to retain control of indigenous land in Chiapas, and in 2000, PRI was voted out of office for the first time in seven decades.

As violent clashes between

campesinos

, Zapatistas, Mexican military, and paramilitary groups continued for more than a decade after the uprising officially ended, Chiapas became one of the most militarized regions in the Americas. The violence did not deter the Zapatistas from practicing self-government, and by 2003, they initiated

Juntas del Buen Gobierno

, a community-based, cooperative political system in which pre-Columbian forms of governance are observed. In this cooperative political system there are no parties, and community members serve as officeholders on a rotational basis. Most of the languages of Chiapas belong to the Western Maya language group. These include Ch'ol, Chontal, Chuj, Jacaltec, Kanjobal, Motozinlec, Tojolabal, Tzeltal, and Tzotzil. A few non-Mayan languages such as Zoque, a Mixe-Zoquean language, are also spoken in the region. Just as the indigenous cultures of Chiapas have been influenced from colonial influence â Tzotzils are mostly protestant Christians, while Tzeltals are mostly Roman Catholic â the languages have also been influenced from the history of sustained contact with Spanish. Spanish loanwords are easy to identify in Tzotzil â

bino

(

vino

âwine'),

martoma

(

mayordomo

âcustodian'), and

rominko

(

domingo

âSunday') among others. The /r/ sound in ârominko' did not exist in either Ch'ol or Tzotzil prior to contact with Spanish, but entered both languages through Spanish loanwords, and has since spread to some native words. The colonial Tzotzil word

*

kelem âyoung man' became

kerem

âboy' in modern Tzotzil. Structural modifications such as these are normal linguistic consequences of language contact and cannot readily be undone, even with the types of strong political intervention that put parts of Chiapas under Zapatista control.

In the Zapatista strongholds of Chiapas where the uprising of 1994 took place, language maintenance is high. Some communities have been successful in stopping or even reversing the cross-generational language shift to Spanish that has been under way since at least the early nineteenth century when Spanish was promoted as the language of Mexico as set forth in Chapter 6. Some Maya languages â Ch'ol, Tojolabal, Tzeltal, and Tzotzil among them â are even considered to be thriving. The vitality of these languages is due to the Zapatista educational system, in which indigenous languages are the medium of instruction but also inform the whole of the curriculum, which is rooted in the Maya tradition of communal living. Because Chiapas is home to nearly 15% of Mexico's total indigenous population and more than 50 distinctive language groups, the focus on local language and culture in Zapatista schools makes sense. The fate of all of these languages is nevertheless at stake, since the issue of land rights remains far from settled.

In 2012, a communiqué issued by the EZLN reached the international press. It read, “Did you hear that? It is the sound of your world crumbling. It is the sound of ours resurging.” On that day, 50,000 Zapatistas â mostly from Tzeltal, Tzotzil, and Ch'ol indigenous communities â returned to the streets of San Cristóbal de las Casas. This time, wielding no weapons, they marched in silence, black balaclavas (ski masks) covering their faces in the style of Subcomandante Marcos. The march coincided with two significant events in the intertwined cultural and political life of the Maya and the Zapatistas: the end of the creation cycle in traditional Maya scripture and the fifteenth anniversary of the Acetal Massacre of 1997 in which 45 unarmed indigenous people were slain by a paramilitary group while attending a prayer meeting.

In the 2000s, with PRI out of power, the Zapatistas shifted their focus to the cultivation of civic life in the autonomous regions and the preservation of traditional indigenous culture. This emphasis is now in question, since after more than a decade on the sidelines, PRI â the Zapatistas' primary political antagonists â returned to power in 2012. However, the 2012 march through the streets of San Cristóbal may have also been a signal that, 20 years following the original uprising, the Zapatistas still hold sway in Chiapas.

The island of Hispaniola, located dead center in the Caribbean Sea, is divided between the western third, which is occupied by the Kreyòl-and-French-speaking nation of Haiti, and the east two-thirds, which is occupied by the Spanish-speaking Dominican Republic. The two countries are separated by the Massacre River, so named for a bloody struggle between the French and the Spanish during the colonial era. The violent colonial past was matched by an equally violent event in the twentieth century, the infamous Parsley Massacre of 1937.

From 1930 to 1961, the Dominican Republic was ruled by the dictator Rafael Trujillo, known in Spanish as

El Jefe

âThe Boss.' He promoted a cult of personality that, among other things, involved renaming Santo Domingo, the capital city, Ciudad Trujillo âTrujillo City.' Trujillo's story is bound with the raceânationâlanguage triad described in Chapter 4. There is evidence that Trujillo used powder and whitening creams to lighten his face in order to appear more European. Trujillo also initiated a so-called open-door immigration policy, in which certain groups, namely the Japanese, Spanish, and Jews, were allowed to seek citizenship in the Dominican Republic. It seems his goal was to lighten the population. He had an equal desire to rid the Dominican Republic of dark-skinned Haitians.

In 1937, as Haitians were leaving the Dominican Republic en masse, Trijillo called in the military to attack the border region and to kill as many exiting Haitians as possible. However, since it was not possible to discern a Haitian from a Dominican on the spot based on apperance alone, a linguistic test was devised. The test exploited the articulatory difference in the pronuncation of [r] between Kreyòl and Spanish. The [r] of Spanish is an alveolar trill, at the beginning of a word like

rojo

âred' and where a double-r appears in orthography, in a word like

perro

âdog.' Elsewhere, it is an alveolar tap [ɾ]. In contrast, the sound in Kreyòl is pronounced as a uvular trill [Ê]. The chosen

word for the linguistic test was

perejil

âparsley.' On the basis of whether your place of articulation of [r] was the alveolar ridge, or about five centimeters back in the oral cavity at the uvula, you either lived or died. Those who pronounced the word with the Spanish tap were free to go. Those who pronounced it with the uvular trill were killed on the spot. Over the course of a few days, 10,000â30,000 Haitians died. The massacre is known in Spanish as

el corte

and in Kreyòl as

kuoto-a

âthe cutting.' We will say it: there is nothing new under the sun.

Trujillo's Parsley Massacre was not the first of its kind. In Biblical times, the Hebrew word

shibboleth

âear of corn' was used by the Gileadites to distinguish the Ephraimites whose language variety did not have phoneme /Ê/. After the Ephraimites lost a battle to the Gileadites, they went to the River Jordan to return home. As a linguistic test to cross the river, the Gileadites had them say the word for âear of corn,' and 42,000 of them were killed when they replied, “Sibboleth.”

Neither were the language silos created in Eastern Europe at the end of World War II an innovation. In the midnineteenth century, the United States government established similar silos, called Indian Reservations, west of the Mississippi. These reservations were set up on the basis of language difference, partitioning the Cherokee (Iroquois) from the Creek (Muskogean) from the Catawba (Sioux) with delineated boundaries like those separating France from Spain and Germany. In pre-Columbian times, the area of what is now modern-day north Georgia was settled by speakers of Cherokee, Creek, and Catawba who encountered one another frequently.

No one can unscramble an egg. Nor can one reverse the effects of history. Neither do we want to say that pre-World War II Europe or the pre-Columbian Americas were Eden. What we do want to say is that now, going forward, language diversity is not a problem, and it does not need to be resolved, through attempts either to segregate language communities against their will or to eradicate languages deemed undesirable or unnecessary by those in positions of power.

Most speakers of Tamil live in Tamil Nadu, a state on the east coast of India that extends south abutting the Bay of Bengal all the way to the southern tip of the subcontinent, where it meets the Indian Ocean. Tamil Nadu is roughly the size of New York State, but has more than three times the number of people. Most of them, some 60 million, speak Tamil. The language is also spoken by about 4 million people in the northeastern part of the island nation of Sri Lanka, which lies due south of Tamil Nadu, and by a few million others in Malaysia, Singapore, and parts of East Africa. The largest concentration of Tamil speakers is in Chennai (formerly Madras), the capital of Tamil Nadu. Tamil is a language in the Tamil branch of the Dravidian language family.

Speakers of Tamil are invested in beliefs about the antiquity of their language and consider Classical (Old) Tamil to be the most pure form of the language. Contemporary speech varieties vary according to caste (sociolects) and region (varieties). Caste differences in speech are highly recognizable. The varieties spoken by Tamil Brahmins, for example, are known as

Braahmik

and are considered to be highly

Sanskritized. The variety spoken in the central part of Tamil Nadu is said to have changed the least from Classical Tamil. The style of this variety spoken by educated non-brahmins in this region is the basis of contemporary Popular Standard Tamil. The Sri Lankan varieties are less influenced by Sanskrit but have borrowings from Portuguese, Dutch, and English. Sri Lankan Tamil and Tamil of Tamil Nadu are sometimes considered mutually unintelligible, and the Sri Lankan varieties are sometimes said to be more similar to Malayalam, another Dravidian language. The remarkable diversity of the Tamil-speaking regions is further complicated by the diglossic situation we describe at the end of this profile.

In most varieties of English, the word âpop' begins with the bilabial stop /p/, âthrow' with the interdental fricative /θ/, âtake' with the alveolar stop /t/, âchocolate' with the alveo-palatal affricate /tÊ/, âyes' with the palatal approximate /j/, and âgood' with the velar stop /É¡/. In making these consonant articulations, ordered here from the front of the mouth to the back, English skips entirely over the part of the oral cavity between the alveolar ridge and the hard palate known as the postalveolar region. This is the place of articulation for retroflex consonants, which are only found in some 20% of the world's languages but which are especially prominent in the languages of South Asia.

Retroflex consonants are formed when the tip of the tongue curls back and makes some type of contact with the postalveolar region. The type of contact depends on the manner of articulation. In Tamil, there are four retroflex consonants with different manners of articulation:

- voiceless retroflex stop/Ê/, as in [eÊÊɯ] âeight';

- voiced retroflex nasal /ɳ/, as in [aɳal] âneck';

- voiced retroflex lateral approximant /É/, as in [puÉi] âtamarind';

- voiced retroflex approximant /É»/, as in [ÊÉÉ»i] âway.'

Approximant consonants are like fricatives in that the articulators approach each other very closely, but unlike fricatives, no turbulent noise is produced. The retroflex approximate /É»/ can be heard in the pronunciation of the name of the language, âTamil,' as [t̪Émɨɻ]. Retroflex articulations often color neighboring vowels, giving them an r-sounding quality in perception.

In terms of phonology, the Tamil retroflex consonants are contrastive, and minimal pairs are found with consonants of the same manner of articulation and different places of articulation. The retroflex nasal /ɳ/, for example, can contrast with the alveolar nasal /n/, creating meaning distinctions in pairs such as

maɳa

âfrangrance' and

mana

âmind.' The retroflex lateral approximate contrasts with the alveolar lateral, yielding minimal pairs such as

puli

âtiger' and

puÉi

âtamarind.'

If you are an English speaker, you may greet an old friend with a form of the salutation âhey' in which the vowel is elongated several times the

usual length (heeeey). Or to emphatically disagree with an interlocutor, you may likewise elongate the /o/ in âno' (noooo) to emphasize your position. Although you do nuance the meaning of the words âhey' and âno' when you do this, you do not fundamentally change their meaning; âno' in effect still means âno.' This is because English does not make use of differences in vowel length to make lexical or grammatical contrasts.

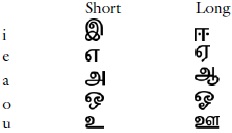

An important characteristic of Tamil phonology is that, in contrast to English, vowel length is used to make phonological meaning contrasts. For each of the five vowel sounds /a, e, i, o, u/, there are phonologically contrastive long variants /aË, eË, iË, oË, uË/. The duration of the long vowels is roughly double that of the short vowels, though the duration varies depending on phonetic environment.

Each of the the 10 vowels is represented in writing with a unique letter.

Lexical minimal pairs illustrate the difference between short and long vowels, for example:

| Short | Long |

| pal âtooth' | paal âmilk' |

| vidi âfate' | viidi âstreet' |

| todu âtouch' | toodu âearring' |

| mudi âhair' | muudi âlid' |

As we mentioned in Chapter 2, some languages group nouns into categories based on what appear to be the natural characteristics that they name. These categories are called noun classes. In many languages of Europe, Africa, and Australia, nouns are classed according to grammatical gender. Grammatical gender is found in about one-fourth of the world's languages, and among them, the masculine/feminine/neuter system of classification found in languages such as German and Polish is especially common. In noun class languages, the classes codetermine, along with case, number, and person, the type of morphology a noun will receive. Adjectives, verbs, and other grammatical elements are also affected in the sense that they must be in grammatical agreement

,

or morphological symmetry, with the noun.

In Tamil, nouns are classed first into one of two semantic âsuperclasses,' known as ârational' and âirrational,' or âhigh caste' and âlow caste.' The rational class aggregates all

uyarthinai

âhumans,'

thevar

âgods,'

naragar

âthe devil,' and other mythical beings. Everything else (abstract nouns, animals, and objects) is grouped together in the irrational class. Grammatical gender, in combination with number, only emerges in the form of subclasses within the superclasses. The rational class comprises

masculine singular, feminine singular, and a plural category that does not distinguish gender. The irrational class comprises subclasses that only distinguish number â singular and plural â and in this respect, irrational nouns can be said to be neuter.

The semantic noun classes in Tamil have morphological and syntactic consequences. First, the classes determine the morphological endings for some of Tamil's 10 cases. The rational feminine noun

penn

âgirl' has a morphology that resembles the irrational noun

maram

âtree' in certain cases (ACC â

penn-ai

,

marath-ai

; DAT â

penn-ukku, marath-ukku

), but for some cases, the endings are distinct (LOC â

penn-idam

,

marath-il

; ABL â

penn-idamirunthu, marath-ilirunthu

). In terms of syntax, two nouns of the same super class can combine in the same noun phrase, while a rational and irrational noun cannot. âMen and women have perished' is a possible utterance because the noun phrase subject comprises two nouns of the same rational class. âMen and tigers have perished' is not possible, since men (rational) and tigers (irrational) come from distinct super classes. In Tamil, this idea is expressed by repeating the predicate, as in âmen have perished and tigers have perished' (Dixon 1982, 170).

In the languages of Europe, subject personal pronouns slot into a familiar pronominal paradigm in which unique forms represent first, second, and third persons in singular and plural number. The Italian pronouns (singular â

io, tu, lui/lei

; plural â

noi, voi, Loro

) is fairly typical of these languages. Each unique subject pronoun (e.g.,

noi

) cooccurs with a unique set of verbal morphology (e.g.,

mangiamo

) in the various verbal tenses. Of note is that Italian, like English and the other languages of Europe, subsumes two senses of the first person plural into a single grammatical form, namely,

noi

or âwe.' The form may mean âwe, you and I' or âwe, I and others but not you.' This means that on occasion, speakers may find themselves in conversations in which it is unclear whether or not the addressee is included as a part of the subject.

In Tamil, these two senses correspond to separate and distinct subject personal pronouns. These forms are known as inclusive, when the addressee is included in the meaning, and exclusive, when the addressee is not included in the meaning. The first-person plural-inclusive is

naam

âwe' (you and I) and the first-person plural-exclusive is

naangal

âwe' (I and others but not you). In some languages that make this distinction, inclusive and exclusive forms cooccur with separate verbal morphology. This is not the case in Tamil, as verbs occurring with both

naam

and

naangal

take the same endings.

Beyond their function in the morphosyntax of Tamil, the inclusive/exclusive distinction also plays an important pragmatic role (Brown and Levinson 1987:203). The inclusive subject pronoun

naam

and the corresponding object and possessive pronouns are used in positive expressions of politeness. In Tamil culture, it is considered rude to refer to âmy mother,' âmy family,' or âmy car.' Instead, inclusive possessives are used to convey a sense of shared ownership. A polite invitation to dinner may invite the addressee to dinner at our (inclusive) home.

Vaanka, namma viiTTlee caappiTalaam.

Come, our-INCL house we eat.

âCome, let's eat at our house.'

As early as the third century BCE, Tamil scholars produced a remarkably sweeping description of the ancient Tamil language, including grammar and phonology, orthography, and the major literary works of the day. This work is known as the

TolkaÌppiyam,

which is derived from the Tamil words

Tonmai

âancient' and

Kappiam

âliterature.' The notions of âlanguage' and âliterature' have therefore been tightly intertwined with one another in the Tamil linguistic imaginary since antiquity, and today the

TolkaÌppiyam

is still considered an important authority on the language.

The Classical literary language, known as

Centamil

, is highly revered in contemporary Tamil culture, and for centuries it has been formally studied by students in schools. No one speaks

Centamil

as a first-language variety. Instead, children learn one of the caste- and regional varieties described earlier in this profile. These varieties are known in general as

Koduntamil.

The functional alternation between these two types of language has created a situation of diglossia similar to that involving Arabic described in Chapter 3. In Tamil Nadu,

Centamil

is the H (high) variety, and

Koduntamil

is the L (low) variety.

In all diglossic situations, the H (high) and L (low) varieties are arranged in complementary distribution, such that in situations where H is used, L is not, and vice versa. H emerges in the formal domains of religion, education, and media, while L is relegated to informal domains, such as in talk between friends. What makes the Tamil diglossic situation unique is that H and L constitute distinct diasystems, or systems of related but distinct language varieties (Britto 1986). In Tamil, the language varieties constituting the H and L diasystems differ in terms of phonology, morphology, and lexicon. The social context and degree of formality determine which variety or varieties within the H or L diasystem continuum will be used. In formal education and religious situations,

Centamil

, the highest of the H varieties, is most commonly spoken. In news media such as television, radio, and newspapers, Popular Standard Tamil is used. This variety is less formal than

Centamil

but still falls within the H diasystem.

The social and pragmatic meanings attached to all H and L varieties are easily understood by Tamil speakers. When a politician begins a speech with formal greetings in one of the H varieties, it is clear that the intent is to establish status, credibility, and authority. When the politician switches to an L variety, listeners appreciate the social meaning: solidarity, warmth, and familiarity. This type of diglossia â constituted by H and L diasystems â has been in place in the Tamil-speaking world for centuries. Full participation in Tamil life requires the ability to command various H and L codes as well as knowledge of the unspoken pragmatic rules for knowing when, where, and how to move between them.