Liars and Outliers (20 page)

Read Liars and Outliers Online

Authors: Bruce Schneier

In this way, our traditional intuition of trust and security fails. There's a fundamental difference between handing a friend your photo album and allowing him to look through it and giving her access to your Flickr account. In the latter case, you're implicitly giving her permission to make copies of your photos that she can keep forever or give to other people.

Our intuitions about trust are contextual. We meet someone, possibly introduced by a mutual friend, and grow to trust her incrementally and over time. This sort of process happens very differently in online communities, and our intuitions aren't necessarily in synch with the new reality. Instead, we are often forced to set explicit rules about trust—whom we allow to see posts, what circles different “friends” are in, whether the whole world can see our photos or only selected people, and so on. Because this is unnatural for people, it's easy to get wrong.

Science is about to give us a completely new way security-augmented reputational pressure can fail. In the next ten years, there's going to be an explosion of results in genetic determinism. We are starting to learn which genes are correlated with which traits, and this will almost certainly be misreported and misunderstood. People may use these genetic markers as a form of reputation. Who knows how this will fall out—whether we'll live in a world like that of the movie

Gattaca

, where a person's genes determine his or her life, or a world where this sort of research is banned, or somewhere in-between. But it's going to be interesting to watch.

I don't mean to imply that it is somehow wrong to use technological security systems to scale societal pressures, or wrong to use security to protect those technological systems. These systems provide us with enormous value, and our society couldn't have grown to its present size or complexity without them. But we have to realize that, like any category of societal pressure, security systems are not perfect, and will allow for some scope of defection. We just need to watch our dependence on the various categories of societal pressure, and ensure that by scaling one particular system and implementing security to protect it, we don't accidentally make the scope of defection worse.

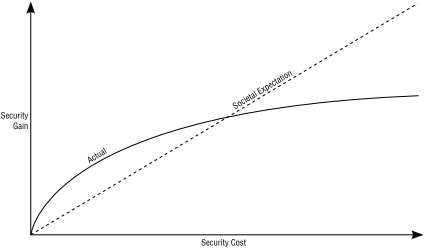

Expenditures on security systems can outweigh the benefits

. Security systems can get very expensive, and there's a point of diminishing returns where you spend increasingly more money and effort on security and get less and less additional security in return.

8

Given a choice between a $20 lock and a $50 lock, the more expensive lock will probably be more secure, and in many cases worth the additional cost. A $100 lock will be even more secure, and might be worth it in some situations. But a $500 lock isn't going to be ten times more secure than a $50 lock. There's going to be a point where the more expensive lock will only be slightly more secure, and not worth the additional cost. There'll also be a point where the burglar will ignore the $500 lock and break the $50 window. But even if you increase the security of your windows and everything else in your house, there's a point where you start to get diminishing returns for your security dollar.

The same analysis works more generally. In the ten years since 9/11, the U.S. has

spent about $1 trillion

fighting terrorism. This

doesn't count the wars

in Iraq and Afghanistan, which total well over $3 trillion. For all of that money, we have not increased our security from terrorism proportionally. If we double our security budget, we won't reduce our terrorism risk by another 50%. And if we increase the budget by ten times, we won't get anywhere near ten times the security. Similarly, if we halve our counterterrorism budget, we won't double our risk. There's a point—and it'll be different for every one of us—where spending more money isn't worth the risk reduction. A

cost-benefit analysis

demonstrates that it's smart to allow a limited amount of criminal activity, just as we observed that you can never get to an all-dove population.

There can be too much security

. Even if technologies were close to perfect, all they could do would be to raise the cost of defection in general. Note that this cost isn't just money, it's freedom, liberty, individualism, time, convenience, and so on. Too much security system pressure lands you in a police state.

Figure 9:

Security's Diminishing Returns

It's impossible to have enough security that every person in every circumstance will cooperate rather than defect. Everybody will make an individual risk trade-off. And since these trade-offs are subjective, and there is so much variation in both individuals and individual situations, the defection rate will never get down to zero. We might possibly, in some science-fiction future, raise the cost of defecting in every particular circumstance to be so high that the benefit of cooperating exceeds that of defecting for any rational actor, but we can never raise it high enough to dissuade all irrational actors. Crimes of passion, for example, are ones where the cost of the crime far outweighs the benefits, so they occur only when

passion overrides rationality

.

Part III

The Real World

Chapter 11

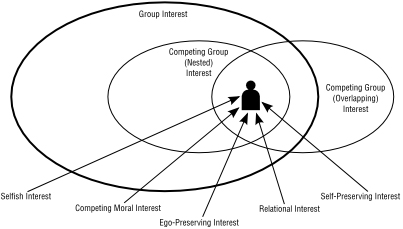

Competing Interests

In a societal dilemma, an individual makes a risk trade-off between the group interest and some competing interest. Until now, we've ignored those competing interests: it's been mostly selfish interests, with the occasional competing moral interest. It's time to fully explore those competing interests.

In general, there are a variety of competing interests that can cause someone to defect and not act according to the group norm:

- Selfish self-interest

. This is the person who cheats, defrauds, steals, and otherwise puts his own selfish interest ahead of the group interest. In extreme cases, he might be a sociopath. - Self-preservation interest

. Someone who is motivated by self-preservation—fear, for example—is much more likely to behave according to her own interest than to adhere to the group norm. For instance, someone might defect because she's being blackmailed. Or she might have a drug addiction, or heavy debts. Jean Valjean from

Les Miserables

, stealing food to feed himself and his family, is a very sympathetic defector. - Ego-preservation interest

. There are a lot of things people do because they want to preserve a vision of who they are as a person. Someone might defect because he believes—rightly or wrongly—that others are already defecting at his expense and he can't stand being seen as a sucker. Broker

Rhonda Breard embezzled

$11.4 million from her clients, driven both by greed and the need to appear rich. - Other psychological motivations

. This is a catch-all category for personal interests that don't fit anywhere else. It includes fears, anxieties, poor impulse control, genuine laziness, and temporary—or permanent—insanity.

Envy can motivate

deception.

1

So can greed or sloth. People do

things out of anger

that they wouldn't otherwise do. Some pretty

heinous behavior

can result from a chronic deprivation of basic human needs. And there's a lot we're still learning about how people make risk trade-offs, especially in

extreme situations

. - Relational interest

. Remaining true to another person is a powerful motivation. Someone might defect from a group in order to protect a friend, relative, lover, or partner. - Group interest of another group

. It's not uncommon for someone to be in two different groups, and for the groups' interests—and norms—to be in conflict. The person has to decide which group to cooperate with and which to defect from. We'll talk about this extensively later in this chapter. - Competing moral interest

. A person's individual morals don't always conform to those of the group, and a person might be morally opposed to the group norm; someone might defect because he believes it is the right thing to do. There are two basic categories here: those who consider a particular moral rule valid in general but believe they have some kind of special reason to override it, and those who believe the rule to be invalid per se. Robin Hood is an example of a defector with a competing moral interest. An extreme example of people with a competing moral interest are suicide bombers, who are convinced that their actions are serving some greater good—one paper calls them “

lethal altruists

.” - Ignorance

. A person might not even realize he's defecting. He might take something, not knowing it is owned by someone. (This is somewhat of a special case, because the person isn't making a risk trade-off.)

An individual might have several simultaneous competing interests, some of them pressuring him towards the group norm and some away from it. In 1943,

Abraham Maslow

ordered human needs in a hierarchy, from the most fundamental to least fundamental: physiological needs, safety, love and belonging, self-esteem, self-actualization, and self-transcendence. Some of those needs advocate cooperation, and others advocate defection.

Figuring out whether to cooperate or defect—and then what norm to follow—means taking all of this into account. I'm not trying to say that people use some conscious calculus to decide when to cooperate and when to defect. This sort of idea is the basis for the

Rational Choice Theory

of economics, which holds that people make trade-offs that are somehow optimal. Their decisions are “rational” not in the sense that they are based solely on reason or profit maximization, but in the much more narrow sense that they minimize costs and maximize benefits, taking risks into account. For example, a burglar would trade off the prospective benefits of robbing a home against the prospective risks and costs of getting caught. A homeowner would likewise trade off the benefits of a burglar alarm system against the costs—both in money and in inconvenience—of installing one.

This mechanistic view of decision making is crumbling in the face of new psychological research into the psychology of decision making. It's being replaced by models of what's called

Bounded Rationality

, which provide a much more realistic picture of how people make these sorts of decisions. For example, we know that much of the

trade-off process

happens in the unconscious part of the brain; people decide in their gut and then construct a conscious rationalization for that decision. These gut decisions often have strong biases shaped by evolution, but we know that a lot of assessment goes into that gut decision and that there are all sorts of contextual effects.

Figure 10:

Competing Interests in a Societal Dilemma

This all gets very complicated very quickly. In 1958, psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg outlined six stages of moral development. Depending on which stage a person is reasoning from, he will make a

different type of trade-off

. The stage of moral reasoning won't determine whether a person will cooperate or defect, but instead will determine what moral arguments he is likely to use to decide.

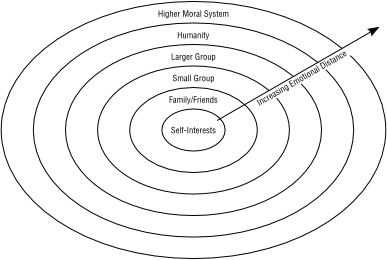

2

More generally, there are several counterbalancing pressures on a person as she makes her trade-off. We can organize pressures from the person outwards: self, kith and kin, less intimate friends, various larger and potentially overlapping groups, society as a whole (however we define that), all of humanity (a special case of society as a whole), and some higher moral system (religion, political or life philosophy, or whatever). Sometimes the pressures come entirely from a person's own head, as with the various self-interests. The rest of the time, they come from other people or groups.

| Kohlberg's Stages of Morality 3 | |

| Level 1: Preconventional Morality | Stage 1: Punishment-avoidance and obedience |

| Right and wrong determined by rewards/punishment. | Makes moral decisions strictly on the basis of self-interest. Disobeys rules, if possible without getting caught. |

| Stage 2: Exchange of favors | |

| Recognizes that others have needs, but makes satisfaction of own needs a higher priority. | |

| Level 2: Conventional Morality | Stage 3: Good boy/good girl |

| Other's views matter. Avoidance of blame; seeking of approval. | Makes decisions on the basis of what will please others. Concerned about maintaining interpersonal relations. |

| Stage 4: Law and order | |

| Looks to society as a whole for guidelines about behavior. Thinks of rules as inflexible, unchangeable. | |

| Level 3: Postconventional Morality | Stage 5: Social contract |

| Abstract notions of justice. Rights of others can override obedience to laws/rules. | Recognizes that rules are social agreements that can be changed when necessary. |

| Stage 6: Universal ethical principles | |

| Adheres to a small number of abstract principles that transcend specific, concrete rules. Answers to an inner moral compass. |

This is important, because the stronger the competing pressure is, the easier it becomes to defect from the group interest. Self-preservation interests can be strong, as can relationship interests. Moral interests can be strong in some people and not in others. Psychological motivations like fears and phobias can be very strong. The group interests of other groups can also be strong, especially if those groups are smaller and more intimate.

4

Scale and emotional distance matters a lot. The diagram gives some feel for this, but—of course—it's very simplistic. Individuals might have different emotional distances to different levels, or a different ordering.

Figure 11:

Scale of Competing Interests

Emily Dickinson

wrote that people choose their own society, then “shut the door” on everyone else.

Competing interests, and therefore competing pressures, can get stronger once defectors start to organize in their own groups. It's one thing for Alice to refuse to cooperate with the police because she believes they're acting immorally. But it's far easier for her to defect once she joins a group of activists who feel the same way. The group provides her with moral arguments she can use to justify their actions, a smaller group she can personally identify with as fellow defectors, advice on how to properly and most effectively defect, and emotional support once she decides to defect. And scale matters here, too. Social pressures work better in small groups, so it's more likely that the morals of a small group trump those of a larger one than the other way round. In a sense, defectors are organizing in a smaller subgroup where cooperating with them means defecting from the larger group.

Depending on their competing interests, people may be more or less invested in the group norm. The selfish interests tend to come from people who are not invested in the group norm, and competing moral interests can come from people who are strongly invested in the group norm while also strongly invested in other norms. Because of these additional investments, they have to explicitly wrestle with the corresponding competing interests, and the trade-offs can become very complicated.

Someone with criminal tendencies might have a simple risk trade-off to make: should I steal or not? But someone who is both moral and invested in the group norm—Jean Valjean or Robin Hood—has a much harder choice. He has to weigh his self-preservation needs, the morality of his actions, the needs of others he's helping, the morality of those he's stealing from, and so on. Of course, there's a lot of individual variation. Some people consider their

morality to be central

to their self-identity, while others consider it to be more peripheral. René Girard uses the term “

spiritual geniuses

” to describe the most moral of people. We also describe many of them as martyrs; being differently moral can be dangerous.

5

Society, of course, wants the group interest to prevail.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

wrote:

Society is a joint-stock company, in which the members agree, for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater. The virtue in most request is conformity. Self-reliance is its aversion. It loves not realities and creators, but names and customs.

Henry David Thoreau

talks about how he went along with the group norm, despite what his morals told him:

The greater part of what my neighbors call good I believe in my soul to be bad, and if I repent of anything, it is very likely to be my good behavior. What demon possessed me that I behaved so well?

When historian

Laurel Thatcher Ulrich

wrote “Well-behaved women seldom make history,” she was referring to defecting.

Socrates's morals

pointed him in the other direction, choosing to cooperate and drink poison rather than defect and escape, even though he knew his sentence was unjust.

We accept that people absorb and live according to the morals of their culture—even to the point of absolution from culpability for actions we now consider immoral—because we examine culpability in light of the commonly available moral standards within the culture

at that

time.

6