Liars and Outliers (8 page)

Read Liars and Outliers Online

Authors: Bruce Schneier

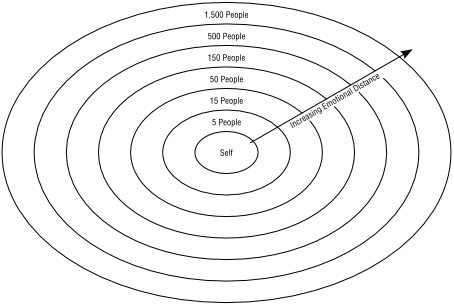

Remember the Dunbar number? Actually, Dunbar proposed several natural human group sizes that increase by a factor of approximately three: 5, 15, 50, 150, 500, and 1,500—although, really, the numbers aren't as precise as all that. The layers relate to both the intensity and intimacy of relationships, and the frequency of contact.

The smallest, three to five, is a

clique

: the number of people from whom you would seek help in times of severe emotional distress. The 12-to-20 person group is the

sympathy group

: people with whom you have a particularly close relationship. After that, 30 to 50 is the typical size of hunter-gatherer overnight camps, generally drawn from a single pool of 150 people. The 500-person group is the

megaband

, and the 1,500-person group is the

tribe

; both terms are common in ethnographic literature. Fifteen hundred is roughly the number of faces we can recognize, and the typical size of a hunter-gatherer society.

9

Evolutionary psychologists are still debating Dunbar's findings, and whether there are as

many distinct levels

as Dunbar postulates. Regardless of how this all shakes out, for our purposes it's enough to notice that as we move from smaller group sizes to larger ones, our informal social pressures

begin to fail

, necessitating the development of more formal ones. A family doesn't need formal rules for sharing food, but a larger group in a communal dining hall will. Small communities don't need birth registration procedures, marriages certified by an authority, laws of inheritance, or rules governing real-estate transfer; larger communities do. Small companies don't need employee name badges, because everyone already knows everyone else; larger companies need them and many other rules besides.

To put it another way, our trust needs are a function of scale. As the number of people we dealt with increased, we no longer knew them well enough to be able to trust their intentions, so our prehistoric trust toolbox started failing. As we developed agriculture and needed to trust more people over increased distance—physical distance, temporal distance, emotional distance—we needed additional societal pressures to elicit trustworthiness at this new scale. As the number of those interactions increased, and as the potential damage the group could do to the individual increased, we needed even more. If humans were incapable of developing these more formal societal pressures, societies either would have stopped growing or would have disintegrated entirely.

Figure 5:

Dunbar Numbers

Agriculture required protecting resources, through violence if necessary. Luckily, two things happened. We invented institutions—government, basically—and we developed technology. Both of them allowed for human societies to grow larger without tearing themselves apart.

Institutions formalized reputational pressure. With government came laws, enforcement, and formal punishment. I'm not implying that the original purpose of government was facilitating trust, only that part of what these formal institutions did was codify the existing societal norms. This codification is a trust mechanism.

History has forgotten all of these early institutions. Some were undoubtedly civil. Some were religious.

10

No one knows the details of how our ancestors made the transition from an extended family to a tribe of several extended families, because they happened thousands of years before anyone got around to inventing writing. Certainly there's overlap between formal reputational and early institutional pressures. It's enough to say that we made the transition, and that we augmented moral and reputational pressures with institutional pressures.

11

This was a critical development, one that gives us the ability to trust people's actions, even if we can't trust their intentions. We reinforced our informal recognition of pair bonds with formal marriage through religious and civil institutions. We added laws about theft, and prescribed specific punishments. A lot of this, at least initially, is formalizing reputational mechanisms so that they scale to larger groups. But something important happens in the transition: institutional pressures require institutions to implement them. Society has to designate a subset of individuals to enforce the laws. Think of elders, guards, police forces, and judicial systems; priests also take on this role.

Institutions also enabled the formation of groups of groups, and subgroups within groups. So small tribes could become part of larger political groupings. Individual churches could become part of a larger religious organization. Companies could have divisions. Government organizations could have departments. Empires could form, and remain stable over many generations. Institutions scale in a way that morals and reputation do not, and this has allowed societies to grow at a rate never before seen on the planet.

The second force that allowed society to scale was technology—both technology in general and security technology specifically. Security systems are the final way we induce trust. Early security mechanisms included building earthen berms, wearing animal skins as camouflage, and digging pit traps. In one sense, security isn't anything new; we learned in Chapter 2 that it's been around almost as long as life itself. That primitive sort of security is what you might call natural defenses, focused on the individual. But when societies got together and realized they could, as a group, implement security systems, security became a form of societal pressure. In a sense, security technologies allow natural defenses to scale to protect against intra-group defection.

Technology also allowed informal social pressures to scale and become what I call societal pressures. Morals could be written down and passed from generation to generation. Reputation could similarly be recorded, and transferred from one person to another. This sort of thing depends a lot on technology: from the Bible and letters of introduction, to online debates on morality, to entries on the Angie's List database.

A good way to think about it is that both institutional pressure and security systems allow us to overcome the limitations of the Dunbar numbers by enabling people to trust systems instead of people. Instead of having to trust individual merchants, people can trust the laws that regulate merchants. Instead of having to evaluate the trustworthiness of individual borrowers, banks and other lending institutions can trust the credit rating system. Instead of trusting that people won't try to rob my house, I can trust the locks on my doors and—if I want to turn it on—my burglar alarm.

Technology changes the efficacy of societal pressures in another way as well. As soon as the different systems of societal pressure themselves need to be secured, it becomes possible for a defector to attack those security systems directly. Once there's a technologically enhanced system of reputational pressure, that system needs to be protected with security technology. So we need signet rings and wax seals to secure letters of introduction, and computer security measures that keep the Angie's List database from being hacked. Similarly, once forensic measures exist to help enforce laws, those forensic measures can be directly targeted. So burglars wear gloves to keep from leaving fingerprints, and file down VINs to prevent stolen cars from being tracked.

There's a bigger change that results from society's increased scale. As society moved from informal social pressures to more formal societal pressures—whether institutional pressures and security systems, or technologically enhanced moral and reputational pressures—the nature of trust changed. Recall our two definitions of trust from Chapter 1: trust of intentions and trust of actions. In smaller societies, we are usually concerned with trust in the first definition. We're intimately familiar with the people we're interacting with, and have a good idea about their intentions. The social pressures induce cooperation in specific instances, but are also concerned with their overall intentions. As society grows and social ties weaken, we lose this intimacy and become more concerned with trust in the second definition. We don't know who we're interacting with, and have no idea about their intentions, so we concern ourselves with their actions. Societal pressures become more about inducing specific actions: compliance.

Compliance isn't as good as actual trustworthiness, but it's good enough. Both elicit trust.

Also through history, technology allowed specialization, which encouraged larger group sizes. For example, a single farmer could grow enough to sustain more people, permitting even greater specialization. In this and other ways, general technological innovations enabled society to grow even larger and more complex. Dunbar's numbers remain constant, but postal services, telegraph, radio, telephone, television, and now the Internet have allowed us to interact with more people than ever before. Travel has grown increasingly fast and increasingly long distance over the millennia, and has allowed us to meet more people face-to-face. Countries have gotten larger, and there are multinational quasi-governmental organizations. Governments have grown more sophisticated. Organizations have grown larger and more geographically dispersed. Businesses have gotten larger; now there are multinational corporations employing hundreds of thousands of people controlling assets across several continents. If your Facebook account has substantially more than 150 friends, you probably only have a superficial connection with many of them.

12

Technology also increases societal complexity. Automation and mass distribution mean one person can affect more people and more of the planet. Long-distance communication, transport, and travel mean that people can affect each other even if they're far away. Governments have gotten larger, both in terms of geographical area and level of complexity. Computer and networking technology mean that things happen faster, and information that might once have been restricted to specialists can be made available to a worldwide audience. These further increases in scale have a major effect on societal pressures, as we'll see in Chapter 16.

None of this is to say that societal pressures result in a fair, equitable, or moral society. The

Code of Hammurabi

from 1700 BC, the first written code of laws in human history, contains some laws that would be considered barbaric today: if a son strikes his father, his hands shall be hewn off; if anyone commits a robbery and is caught, he shall be put to death; if anyone brings an accusation of any crime before the elders, and does not prove what he has charged, he shall, if a capital offense is charged, be put to death. And world history is filled with governments that have oppressed, persecuted, and even massacred their own people. There's nothing to guarantee that the majority actually approves of these laws; societal interest and societal norms might be dictated by an authoritarian ruler. The only thing societal pressures guarantee is that, in the short run at least, society doesn't fall apart.

Furthermore, societal pressures protect a society from change: bad, good, and indeterminate. Cooperators are, by definition, those who follow the group norm. They put the group interest ahead of any competing interests, and by doing so, make it harder for the group norm to change. If the group norm is unsustainable, this can fatally harm society in the long run.

Remember that society as a whole isn't the only group we're concerned about here. Societal pressures can be found in any group situation. They're how a group of friends protect themselves from greedy people at communal dinners. They enable criminal organizations to protect themselves from loose cannons and potential turncoats within their own ranks. And they're how a military protects itself from deserters and insubordinates, and how corporations protect themselves from embezzling employees.

Chapter 5

Societal Dilemmas

Here are some questions related to trust:

- During a natural disaster, should I steal a big-screen TV? What about food to feed my family?

- As a kamikaze pilot, should I refuse to kill myself? What if I'm just a foot soldier being ordered to attack a heavily armed enemy bunker?

- As a company employee, should I work hard or slack off? What if the people around me are slacking off and getting away with it? What if my job is critical and, by slacking off, I harm everyone else's year-end bonuses?

There's a

risk trade-off

at the heart of every one of these questions. When deciding whether to cooperate and follow the group norm, or defect and follow some competing norm, an individual has to weigh the costs and benefits of each option. I'm going to use a construct I call a societal dilemma to capture the tension between group interest and a competing interest.

What makes something a societal dilemma, and not just an individual's free choice to do whatever he wants and risk the consequences, is that there are societal repercussions of the trade-off. Society as a whole cares about the dilemma, because if enough people defect, something extreme happens. It might be bad, like widespread famine, or it might be good, like civil rights. But since a societal dilemma is from the point of view of societal norms, by definition it's in society's collective best interest to ensure widespread cooperation.

Let's start with the smallest society possible: two people. Another model from game theory works here. It's called the Prisoner's Dilemma.

1

Alice and Bob are partners in crime, and they've both been arrested for burglary.

2

The police don't have enough evidence to convict either of them, so they bring them into separate interrogation rooms and offer each one a deal. “If you betray your accomplice and agree to testify against her,” the policeman says, “I'll let you go free and your partner will get ten years in jail. If you both betray each other, we don't need your testimony, and you'll each get six years in jail. But if you cooperate with your partner and both refuse to say anything, I can only convict you on a minor charge—one year in jail.”

3

Neither Alice nor Bob is fully in charge of his or her own destiny, since the outcome for each depends on the other's decision. Neither has any way of knowing, or influencing, the other's decision; and they don't trust each other.

Imagine Alice evaluating her two options: “If Bob stays silent,” she thinks, “then it would be in my best interest to testify against him. It's a choice between no jail time versus one year in jail, and that's an easy choice. Similarly, if Bob rats on me, it's also in my interest to testify. That's a choice between six years in jail versus ten years in jail. Because I have no control over Bob's decision, testifying gives me the better outcome, regardless of what he chooses to do. It's obviously in my best interest to betray Bob: to confess and agree to testify against him.” That's what she decides to do.

Bob, in a holding cell down the hall, is evaluating the same options. He goes through the same reasoning—he doesn't care about Alice any more than she cares about him—and arrives at the same conclusion.

So both Alice and Bob confess. The police no longer need either one to testify against the other, and each spends six years in jail. But here's the rub: if they had both remained silent, each would have spent only one year in jail.

| Societal Dilemma: Prisoners confessing. | |

| Society: A group of two prisoners. | |

| Group interest: Minimize total jail time for all involved. | Competing interest: Minimize individual jail time. |

| Group norm: To cooperate with the other prisoner and remain silent. | Corresponding defection: Testify against the other. |

The Prisoner's Dilemma encapsulates the conflict between group interest and self-interest. As a pair, Alice and Bob are best off if they both remain silent and spend only one year in jail. But by each following his or her own self-interest, they both end up with worse outcomes individually.

The only way they can end up with the best outcome—one year in jail, as opposed to six, or ten—is by acting in their group interest. Of course, that only makes sense if each can trust the other to do the same. But Alice and Bob can't.

Borrowing a term from economics, the other prisoner's jail time is an

externality

. That is, it's an effect of a decision not borne by the decision maker. To Alice, Bob's jail time is an externality. And to Bob, Alice's jail time is an externality.

I like the prisoner story because it's a reminder that cooperation doesn't imply anything moral; it just means going along with the group norm. Similarly, defection doesn't necessarily imply anything immoral; it just means putting some competing interest ahead of the group interest.

Basic commerce is another type of Prisoner's Dilemma, although you might not have thought about it that way before. Cognitive scientist

Douglas Hofstadter

liked this story better than prisoners, confessions, and jail time.

Two people meet and exchange closed bags, with the understanding that one of them contains money, and the other contains a purchase. Either player can choose to honor the deal by putting into his or her bag what he or she agreed, or he or she can defect by handing over an empty bag.

It's easy to see one trust mechanism that keeps merchants from cheating: their reputations as merchants. It's also easy to see a measure that keeps customers from cheating: they're likely to be arrested or at least barred from the store. These are examples of societal pressures, and they'll return in the next chapters.

This example illustrates something else that's important: societal dilemmas are not always symmetrical. The merchant and a customer have different roles, and different options for cooperating and defecting. They also have different incentives to defect, and different competing norms.

Here's a societal dilemma involving two companies. They are selling identical products at identical prices, with identical customer service and everything else. Sunoco and Amoco gasoline, perhaps. They are the only companies selling those products, and there's a fixed number of customers for them to divvy up. The only way they can increase their market share is by advertising, and any increase in market share comes at the expense of the other company's. For simplicity's sake, assume that each can spend either a fixed amount on advertising or none at all; there isn't a variable amount of advertising spending that they can do. Also assume that if one advertises and the other does not, the company that advertises gains an increase in market share that more than makes up for the advertising investment. If both advertise, their investments cancel each other out and market share stays the same for each. Here's the question: advertise or not?

It's the same risk trade-off as before. From Alice's perspective, if she advertises and Bob does not, she increases her market share. But if she doesn't advertise and Bob does, she loses market share. She's better off advertising, regardless of what Bob does. Bob makes the same trade-off, so they both end up advertising and see no change in market share, when they would both have been better off saving their money.

| Societal Dilemma: Advertising. | |

| Society: Two companies selling the same product. | |

| Group interest: Maximize profits. | Competing interest: Maximize profits at the expense of the other company. |

| Group norm: To not engage in a costly and fruitless advertising arms race, and not advertise. | Corresponding defection: Advertise. |

This is your basic arms race, in which the various factions expend effort just to stay in the same place relative to each other. The USA and the USSR did this during the Cold War. Rival political parties do it, too.

If you assume the individuals can switch between strategies and you set the parameters right, the Hawk-Dove game is a Prisoner's Dilemma. When pairs of individuals interact, they each have the choice of cooperating (being a dove) or defecting (being a hawk). Both individuals know that cooperating is the best strategy for them as a pair, but that individually they're each better off being a hawk.

Not every interaction between two people involves a Prisoner's Dilemma. Imagine two drivers who are both stuck because a tree is blocking the road. The tree is too heavy for one person to move on his own, but it can be moved if they work together. Here, there's no conflict. It is in both their selfish interest and their group interest to move the tree together. But Prisoner's Dilemmas are common, and once you're primed to notice them, you'll start seeing them everywhere.

4

The basic Prisoner's Dilemma formula involves two people who must decide between their own self-interest and the interest of their two-person group. This is interesting—and has been studied extensively

5

—but it's too simplistic for our purposes. We are more concerned with scenarios involving larger groups, with dozens, hundreds, thousands, even millions of people in a single dilemma.

Here's a classic societal dilemma: overfishing. As long as you don't catch too many fish in any area, the remaining fish can breed fast enough to keep up with demand. But if you start taking too many fish out of the water, the remaining fish can't breed fast enough and the whole population collapses.

If there were only one fisher, she could decide how much fish to catch based on both her immediate and long-term interests. She could catch all the fish she was able to in one year, and make a lot of money. Or she could catch fewer fish this year, making less money, but ensuring herself an income for years to come. It's a pretty easy decision to make—assuming she's not engaged in subsistence fishing—and you can imagine that in most instances, the fisher would not sacrifice her future livelihood for a short-term gain.

But as soon as there's more than one boat in the water, things become more complicated. Each fisher not only has to worry about overfishing the waters herself, but whether the other fishers are doing the same. There's a societal dilemma at the core of each one of their decisions.

| Societal Dilemma: Overfishing. | |

| Society: A group of fishers all fishing out of the same waters. | |

| Group interest: The productivity of the fishing waters over the long term. | Competing interest: Short-term profit. |

| Group norm: To limit individual catches. | Corresponding defection: Take more than your share of fish. |

Fisher Alice's trade-off includes the same elements as Prisoner Alice's trade-off. Alice can either act in her short-term self-interest and catch a lot of fish, or act in the group interest of all the local fishers and catch fewer fish. If everyone else acts in the group interest, then Alice is better off acting in her own selfish interest. She'll catch more fish, and fishing stocks will remain strong because she's the only one overfishing. But if Alice acts in the group interest while others act in their self-interest, she'll have sacrificed her own short-term gain for nothing: she'll catch fewer fish, and the fishing stocks will still collapse due to everyone else's overfishing.

Her analysis leads to the decision to overfish. That makes sense, but—of course—if everyone acts according to the same analysis, they'll end up collapsing the fishing stocks and ruining the industry for everyone. This is called a

Tragedy of the Commons

, and was first described by the ecologist Garrett Hardin in 1968.

6

A Tragedy of the Commons occurs whenever a group shares a limited resource: not just fisheries, but grazing lands, water rights, time on a piece of shared exercise equipment at a gym, an unguarded plate of cookies in the kitchen. In a forest, you can cut everything down for maximum short-term profit, or selectively harvest for sustainability. Someone who owns the forest can make the trade-off for himself, but when an unorganized group together owns the forest there's no one to limit the harvest, and a Tragedy of the Commons can result.

A Tragedy of the Commons is more complicated than a two-person Prisoner's Dilemma, because the other fishers aren't making this decision collectively. Instead, each individual fisher decides for himself what to do. In the two-person dilemma, Alice had to try to predict what Bob would do. In this larger dilemma, many more outcomes are possible.

Assume there are 100 fishers in total. Any number from 0 through 100 could act in their selfish interest and overfish. Harm to the group would increase as the scope of overfishing increases, regardless of what Alice does. Alice would probably not be harmed at all by 1 fisher overfishing, and she would be significantly harmed if all 99 chose to do the same. Fifty overfishers would cause some amount of harm; 20, a lesser amount. There are degrees of overfishing. Twenty fishers who each overfish by a small amount might do less damage to the fish stocks than 5 who take everything they can out of the water. What matters here is the scope of defection: the number of overfishers, but also the frequency of overfishing, and the magnitude of each overfishing incident.