Liars and Outliers (32 page)

Read Liars and Outliers Online

Authors: Bruce Schneier

What's going on here is that the definition of “society” is changing. “Society as a whole” has less meaning in a polarized political climate such as the one in the U.S. in the early 21st century. People are defining their society as those who agree with them politically, and the other political side as “traitors,” people who “hate America,” or people who “want the terrorists to win.” It's no surprise that there's widespread defection: with regard to the new, more restrictive, definition of “society,” it's not defection at all.

15

Chapter 16

Technological Advances

Scale is one of the critical concepts necessary to understand societal pressures. The increasing scale of society is what forces us to shift from trust and trustworthiness based on personal relationships to impersonal trust—predictability and compliance—in both people and systems. Increasing scale is what forces us to augment our social pressures of morals and reputation with institutional pressure and security systems. Increasing scale is what's requiring more—and more complicated—security systems, making overall societal pressures more expensive and less effective. Increasing scale makes the failures more expensive and more onerous. And it makes our whole societal pressure system less flexible and adaptable.

This is all because increasing scale affects societal pressures from a number of different directions.

- More people.

Having more people in society changes the effectiveness of different reputational pressures. It also increases the number of defectors, even if the percentage remains unchanged, giving them more opportunities to organize and grow stronger. Finally, more defectors makes it more likely that the defecting behavior is perceived as normal, which can result in a Bad Apple Effect. - Increased complexity.

More people means more interactions among people: more interactions, more often, over longer distances, about more things. This both causes new societal dilemmas to arise and causes interdependencies among dilemmas. Complex systems need to rely on technology more. This means that they

have more flaws

and can

fail in surprising

and catastrophic ways. - New systems.

As more and different technology permeates our lives and our societies, we find new areas of concern that need to be addressed, new societal dilemmas, and new opportunities for defection. Airplane terrorism simply wasn't a problem before airplanes were invented; Internet fraud requires the Internet. The job of the defenders keeps getting bigger. - New security systems.

Technology gives certain societal pressure systems—specifically, reputational and institutional—the ability to scale. Those systems themselves require security, and that security can be attacked directly. So online reputation systems can be poisoned with fake data, or the computers that maintain them can be hacked and the data modified. Our webmail accounts can be hacked, and scammers can post messages asking for money in our name. Or our identities can be stolen from information taken from our home computers or centralized databases. - Increased technological intensity.

As society gets more technological, the amount of damage defectors can do grows. This means that even a very small defection rate can be as bad as a greater defection rate would have been when society was less technologically intense. This holds true for the sociopath intent on killing as many people as possible, and for a company intent on making as much profit as possible, regardless of the environmental damage. In both cases, technology increases the actor's potential harm. Think of how much damage a terrorist can do today versus what he could have done fifty years ago, and then try to extrapolate to what upcoming technologies might enable him to do fifty years from now.

1

Technology also allows defectors to better organize, potentially making their groups larger, more powerful, and more potent. - Increased frequency.

Frequency scales with technology as well. Think of the difference between someone robbing a bank with a gun and a getaway car versus someone stealing from a bank remotely over the Internet. The latter is much more efficient. If the hacker can automate his attack, he can steal from thousands of banks a day—even while he sleeps.

This aspect of scale

is becoming much more important as more aspects of our society are controlled not by people but by automatic systems. - Increased distance.

Defectors can act over both longer physical distances and greater time intervals. This matters because greater distances create the potential for more people, with weaker social ties, to be involved; this weakens moral and reputational pressure. And when physical distances cross national boundaries, institutional pressure becomes less effective as well. - Increased inertia and resistance to change.

Larger groups make slower decisions; and once made, those decisions persist and may be very difficult to reverse or revise. This can cause societal pressures to stagnate.

In prehistoric times, the scale was smaller, and our emergent social pressures—moral and reputational—worked well because they evolved for the small-scale societies of the day. As civilization emerged and technology advanced, we invented institutions to help deal with societal dilemmas on the larger scales of our growing societies. We also invented security technologies to further enhance societal pressures. We needed to trust both these institutions and the security systems that increasingly affected our lives.

We also developed less tolerance for risk. For much of our species' history, life was dangerous. I'm not just talking about losing 15–25% of males to warfare in primitive societies, but infant mortality, childhood diseases, adult diseases, natural and man-made accidents, and violence from both man and beast. As technology, especially medical technology, improved, life became safer and longer. Our tolerance for risk diminished because there were fewer hazards in our lives. (Large, long-term risks like nuclear weapons, genetic engineering, and global warming are much harder for us to comprehend, and we

tend to minimize

them as a result.)

Today, societal scale continues to grow as global trade increases, the world's economies link up, global interdependencies multiply, and international legal bodies gain more power. On a more personal level, the Internet continues to bring distant people closer. Our risk tolerance has become so low that we have a fetish for eliminating—or at least

pretending to eliminate

—as much risk as possible from our lives.

Let's get back to societal pressures as a series of knobs. Technology is continuously improving, making new things possible and existing things easier, cheaper, better, or more reliable. But these same technological advances result in the

knobs being twiddled

in unpredictable ways. Also, as scale increases, new knobs get created, more people have their hands on the knobs, and knobs regulating different dilemmas get interlinked.

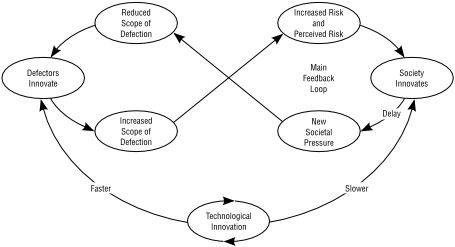

New technologies, new innovations, and new ideas increase the scope of defection in several dimensions. Defectors innovate. Attacks become easier, cheaper, more reliable. New attacks become possible. More people may defect because it's easier to do so, or their defections become more frequent or more intense.

This results in a security imbalance; the knob settings that society had deemed acceptable no longer are. In response, society innovates. It implements new societal pressures. Perhaps they're based on new laws or new technology, perhaps there is some new group norm that gets reflected in society's reputational pressure, or perhaps it's more of what used to work. It's hard to get right at first, because of all the feedback loops we discussed, but eventually society settles on some new knob settings, and the scope of defection is reduced to whatever new level society deems tolerable. And then society is stable until the next technological innovation.

Figure 14:

Societal Pressure Red Queen Effect

If

Figure 14

looks familiar, it's because it's almost the same as

Figure 3

from Chapter 2. This is a Red Queen Effect, fueled not just by natural selection but also by technological innovation. Think of airport security, counterfeiting, or software systems. The attackers improve, so the defenders improve, so the attackers improve, and so on. Both sides must continuously improve just to keep pace.

But it's not a normal Red Queen Effect; this one isn't fair. Defectors have a natural advantage, because they can make use of innovations to attack systems faster than society can use those innovations to defend itself. One of society's disadvantages is the delay between new societal pressures, and a corresponding change in the scope of defection, which we talked about in the previous chapter. In fact, the right half of

Figure 14

is the same as the main feedback loop of

Figure 13

, but with less detail.

More generally, defectors are quicker to use technological innovations. Society has to implement any new security technology as a group, which implies agreement and coordination and—in some instances—a lengthy bureaucratic procurement process. Unfamiliarity is also an issue. Meanwhile, a defector can just use the new technology. For example, it's easier for a bank robber to use his new motorcar as a getaway vehicle than it is for the police department to decide it needs one, get the budget to buy one, choose which one to buy, buy it, and then develop training and policies for it. And if only one police department does this, the bank robber can just move to another town. Corporations can make use of new technologies of influence and persuasion faster than society can develop resistance to them. It's easier for

hackers to find

security flaws in phone switches than it is for the phone companies to upgrade them.

Criminals can form

international partnerships faster than governments can. Defectors are more agile and more adaptable, making them much better at being early adopters of new technology.

We saw it in law enforcement's initial inability to deal with Internet crime.

Criminals were simply

more flexible. Traditional criminal organizations like the Mafia didn't move immediately onto the Internet; instead, new Internet-savvy criminals sprung up. They established websites like CardersMarket and DarkMarket, and established new crime organizations within a decade or so of the Internet's commercialization. Meanwhile, law enforcement simply didn't have the organizational fluidity to adapt as quickly. They couldn't fire their old-school detectives and replace them with people who understood the Internet. Their natural inertia and their tendency to sweep problems under the rug slowed things even more. They had to spend the better part of a decade playing catch-up.

There's one more problem. Defenders are in what the 19th-century military strategist Carl von Clausewitz called “the

position of the interior

.” They have to defend against every possible attack, while the defector just has to find one flaw and one way through the defenses. As systems get more complicated due to technology, more attacks become possible. This means defectors have a first-mover advantage; they get to try the new attack first. As a result, society is constantly responding: shoe scanners in response to the shoe bomber, harder-to-counterfeit money in response to better counterfeiting technologies, better anti-virus software to combat the new computer viruses, and so on. The attacker's clear advantage increases the scope of defection further.

Of course, there are exceptions. Sometimes societal pressures improve without it being a reaction to an increase in the scope of defection. There are technologies that immediately benefit the defender and are of no use at all to the attacker. Fingerprint technology allowed police to identify suspects after they left the scene of the crime, and didn't provide any corresponding benefit to criminals, for example. The same thing happened with immobilizing technology for cars, alarm systems for houses, and computer authentication technologies. Some technologies benefit both, but still give more advantage to the defenders. The radio allowed street policemen to communicate remotely, which makes us safer than criminals communicating remotely endangers us.

Still, we tend to be reactive in security, and only implement new measures in response to an increased scope of defection.

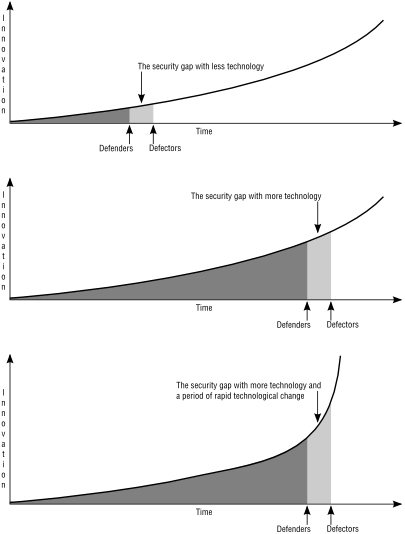

Because the attackers generally innovate faster than the defenders, society needs time to get societal pressures right. The result of this is a security gap: the difference between the scope of defection that society is willing to tolerate and the scope of defection that exists. Generally, this gap hasn't been an insurmountable problem. Sure, some defectors are able to get away with whatever it is they're doing—sometimes for years or even decades—but society generally figures it out in the end. Technology has progressed slowly enough for the Red Queen Effect to work properly. And the slowness has even helped in some situations by minimizing overreactions.

The problem gets worse as technology improves, though. Look at

Figure 15

. On the top, you can see the difference between the defectors' use of technological innovation to attack systems and the defenders' use of technological innovations in security systems and other types of societal pressures. The security gap arising from the fact that the attackers are faster than the defenders is represented by the area under the technology curve between the two lines.

Figure 15:

The Security Gap