Liars and Outliers (10 page)

Read Liars and Outliers Online

Authors: Bruce Schneier

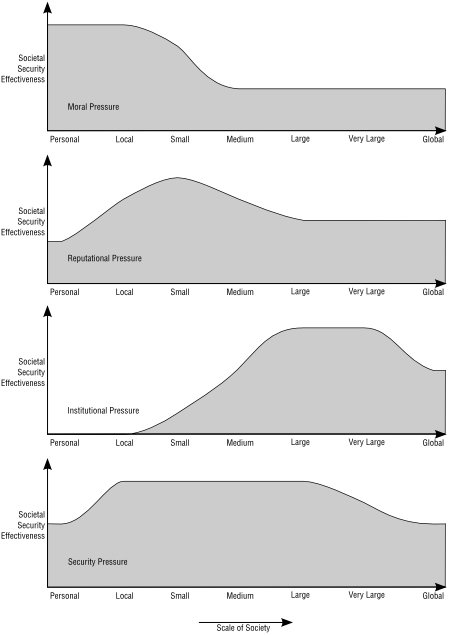

Figure 6:

Societal Pressure Knobs

Think back to the Hawk-Dove game, and the knobs society can use to set the initial parameters. The categories in that figure are all individual knobs, and societal pressures provide a mechanism for the group to control those knobs. In theory, if the knobs are calibrated perfectly, society will get the exact scope of defection it's willing to tolerate.

There are many ways to sort societal pressures. The system I'm using sorts them by origin: moral pressures, reputational pressures, institutional pressures, and security systems.

10

These are categories you've certainly felt yourself. We feel moral pressure to do the right thing or—at least—to not do the wrong thing. Reputational pressure is more commonly known as peer pressure, but I mean any incentives to cooperate that stem from other people. Institutional pressure is broader and more general: the group using rules to induce cooperation. Security systems comprise a weird hybrid: it's both a separate category, and it enhances the other three categories.

The most important difference among these four categories is the scale at which they operate.

- Moral pressure works best in small groups

. Yes, our morals can affect our interactions with strangers on the other side of the planet, but in general, they work best with people we know well. - Reputational pressure works well in small- and medium-sized groups

. If we're not at least somewhat familiar with other people, we're not going to be able to know their reputations. And the better we know them, the more accurately we will know their reputations. - Institutional pressure works best in larger-sized groups

. It often makes no sense in small groups; you're unlikely to call the police if your kid sister steals your bicycle, for example. It can scale to very large groups—even globally—but with difficulty. - Security systems can act as societal pressures at a variety of scales

. They can be up close and personal, like a suit of armor. They can be global, like the systems to detect international money laundering. They can be anything in between.

I'm being deliberately vague about group sizes here, but there definitely is a scale consideration with societal pressures. And because the increasing scale of our society is one of the primary reasons our societal pressure systems are failing, it's important to keep these considerations in mind.

Another difference between the categories of societal pressure is that they operate at distinct times during a security event. Moral pressure can operate either before, during, or after an individual defects. Reputational, as well as most institutional, pressure operates after the defection, although some institutional pressure operates during. Security can operate before, during, or after.

Any measures that operate during or after the event affect the trade-off through a feedback loop. Someone who knows of the negative outcome—perhaps ostracism due to a bad reputation, or a jail sentence—either through direct knowledge or through seeing it happen to someone else, might refrain from defecting in order to avoid it. This is deterrence.

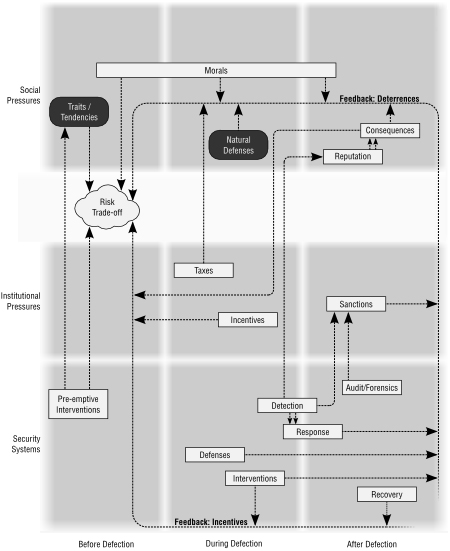

All of this, and more, is illustrated in the complicated block diagram below. Along the bottom axis is the timeline: before, during, and after defection. Along the left are the different categories of societal pressure: moral and reputational (considered together), institutional, and security systems. The traits/tendencies box represents the physical and emotional aspects of people that make them more or less likely to defect. Natural defenses are aspects of targets that make them more or less difficult to attack. Neither of these are societal pressure systems, but I include them for the sake of completeness.

An example might be useful here. Alice is deciding whether to burglarize a house. The group interest is for her not to burglarize the house, but she has some competing interest—it doesn't matter what it is—that makes her want to burglarize the house. Different pressures affect her risk trade-off in different ways.

- Traits/tendencies. If Alice is afraid of heights, she won't try to break in through a second-story window. If she has a broken leg, she probably won't try to break in at all. These considerations operate before defection, at the point of the risk trade-off, when she's deciding whether or not to burglarize the house. (Note that this is not societal pressure.)

- Natural defenses operate during the burglary. Maybe the owner of the house is home and might tackle Alice. (Again, note that this is not societal pressure.)

- Most moral pressures operate at the point of the risk trade-off, or decision: Alice's sense of fairness, sense of right and wrong, and desire to obey the law. Some operate during the actual burglary: feelings of empathy, for example. Some operate after she's committed her crime: guilt, shame, and so on.

- Reputational pressures, assuming she's caught, operate after she's done burglarizing the house. They stem from the reactions and responses of others.

- Institutional pressures also operate after she's done burglarizing the house. Think of laws and mechanisms to punish the guilty in this case.

- Security systems can operate before, during, or after. Preemptive interventions, including incarcerating Alice before she commits the crime or forcing her to take some mood-altering medication that makes her not want to burglarize houses, operate before. Defenses operate during: door locks and window bars make it harder for her to burglarize the house. Detection systems can operate during or after: a burglar alarm calls a response that may or may not come in time. Interventions, like camouflage and authentication systems, operate during as well. Forensic systems operate afterwards, and may identify Alice as the burglar. There's one more type of security system: recovery systems that operate after a burglary can provide a perverse incentive to those aware that the consequences of their misbehavior can be mitigated at no cost to themselves. If Alice knows the house owner can easily recover from a burglary—maybe he has a lot of money, or good insurance—she's more likely to burglarize him.

Figure 7:

The Scale of Different Societal Pressures

Figure 8:

How Societal Pressures Influence the Risk Trade-Off

Systems that work during or after the burglary usually have a deterrence effect. Alice is less likely to burglarize a house if she knows the police are diligent and jail sentences are severe. Or if she knows there's a homeowner who is skilled at karate, or has a burglar alarm.

These categories are not meant to be rigid. There are going to be societal pressures that don't fit neatly into any one category. That's okay; these categories are more meant to be a way of broadly understanding the topic as a whole than a formal taxonomy.

In the next four chapters, I'll outline each type of societal pressure in turn. I'll talk about how they work, and how they fail.

Societal pressure failures occur when the scope of defection is either too high or too low: either there are too many burglaries, or we're spending too much money on security to prevent burglary. This is not the same as individual burglaries; if someone's house was burglarized, it's not necessarily a societal security failure. Remember, we can never get the number of hawks down to zero; and sooner or later, further reducing their number becomes prohibitively expensive.

In some ways, societal pressures are like a group's immune system. Like antibodies, T cells, and B cells, they defend society as a whole against internal threats without being particularly concerned about harm to individual members of the group. The protection is not perfect, but having several different mechanisms that target different threats in different ways—much as an immune system does—makes it stronger.

Chapter 7

Moral Pressures

Looking back at all the elections I've had the opportunity to vote in, there has never been one whose outcome I affected in any way. My voting has never even changed the vote percentages in any perceptible way. If I decided to never vote again, democracy wouldn't notice. It would certainly be in my best interest

not to vote

. Voting is a pain. I have to drive to the polling place, stand in line, then drive home.

1

I'm a busy guy.

Voting is a societal dilemma. For any single individual, there are no benefits to voting. Yes, your vote counts—it just doesn't matter. The rare examples of small elections decided by one vote don't change the central point: voting isn't worth the trouble. But if no one voted, democracy wouldn't work.

Still,

people vote

. It makes sense if 1) the voters see a difference between the two candidates, and 2) they care at least a little bit about the welfare of their fellow citizens. Studies with

actual voters

bear this out.

2

| Societal Dilemma: Voting. | |

| Society: Society as a whole. | |

| Group interest: A robust democracy. | Competing interest: Do what you want to do on election day. |

| Group norm: Vote. | Corresponding defection: Don't bother voting. |

| To encourage people to act in the group interest, society implements these societal pressures: Moral: People tend to feel good when they vote and bad when they don't vote, because they care about their welfare and that of their fellow citizens. |

Caring about the welfare of your fellow citizens is an example of a moral pressure.

3

To further increase voter turnout, society can directly appeal to morals. We impress upon citizens the importance of the issues at stake in the election; we even frame some of the issues in explicitly moral terms. We instill in them a sense of voting as a civic duty. We evoke their sense of group membership, and remind them that their peers are voting. We even scare them, warning that if they don't vote, the remaining voters—who probably don't agree with them politically—will decide the election.

Murder is another societal dilemma. There might be times when it is in our individual self-interest to kill someone else, but it's definitely in the group interest that murder not run rampant. To help prevent this from happening, society has evolved explicit moral prohibitions against murder, such as the Sixth (or Fifth, in the Roman Catholic and Lutheran traditional number) Commandment, “Thou shalt not kill.”

Morality is a complex concept, and the subject of thousands of years' worth of philosophical and theological debate. Although the word “moral” often refers to an individual's values—with “moral” meaning “good,” and “immoral” meaning “bad”—I am using the term “morals” here very generally, to mean any innate or cultural guidelines that inform people's decision-making processes as they evaluate potential trade-offs.

4

These encompass conscious and unconscious processes, explicit rules and gut feelings, deliberate thoughts, and automatic reactions. These also encompass internal reward mechanisms, for both cooperation and defection. Looking back at

Figure 8

in Chapter 6, there is going to be considerable overlap between morals and what I called “traits/tendencies”—I hope to ignore that as well. As we saw in Chapter 3, all sorts of physiological processes make us prone to prosocial behaviors like cooperation and altruism. I'm lumping all of these under the rubric of morals.

And while morals can play a large part in someone's risk trade-off, in this chapter I am just focusing on how morals act as a societal pressure system to reduce the scope of defection. In Chapter 11, I'll discuss how morals affect the decision to cooperate or defect more broadly.

Beliefs that voting is the right thing to do, and that murdering someone is wrong, are examples of moral pressure: a mechanism designed to engage people's sense of right and wrong. Natural selection has

modified our brains

so that trust, altruism, and cooperation feel good, but—as we well know—that doesn't mean we're always trustworthy, altruistic, and cooperative. In both of the above examples, voting and murder, morals aren't very effective. With voting, a large defection rate isn't too much of a problem. U.S. presidential elections are decided by about half the pool of eligible voters.

5

Elections for lesser offices are decided by an even smaller percentage. But while this is certainly a social issue, the harm non-voters cause is minimal.

With murder, the number of defectors is both smaller and more harmful. In 2010,

the murder rate

in the U.S. was 5.0 per 100,000 people.

Elsewhere in the

world, it ranges from 0.39 per 100,000 in the relatively murder-free nation of Singapore, to an astonishing 58 per 100,000 in El Salvador.

Morals affect societal dilemmas in a variety of ways. They can affect us at the time of the risk trade-off, by making us feel good or bad about a particular cooperate/defect decision. They can affect us after we've made the decision and during the actual defection: empathy for our victims, for example. And they can affect us after the defection, through feelings of guilt, shame, pride, satisfaction, and so on. Anticipating moral feelings that may arise during and after defection provides either an incentive to cooperate or a deterrent from defection.

At the risk of opening a large philosophical can of worms, I'll venture to say that morals are unique in being the only societal pressure that makes people “want to” behave in the group interest. The other three mechanisms make them “have to.”

There are two basic types of morals that affect risk trade-offs, one general and the other specific. First, the general. The human evolutionary tendencies toward trust and cooperation discussed in Chapter 3 are reflected in our moral, ethical, and religious codes. These codes vary wildly, but all emphasize prosocial behaviors like altruism, fairness, cooperation, and trust. The most general of these is the Golden Rule: “Do unto others what you would have them do unto you.” Different groups have their own unique spin on the

Golden Rule

, but it's basically an admonition to cooperate with others. It really is the closest thing to a universal moral principle our species has.

6

Moral reminders don't have to be anything formal. They can be as informal as the proverbs—which are anything but simplistic—that we use to teach our children; and cultures everywhere have proverbs about altruism, diligence, fidelity, and being a cooperating member of the community.

7

The models of the world we learn sometimes have moral components, too.

This can go several ways. You might learn not to defecate upstream of your village because you've been taught about cholera, or because you've been taught that doing so will make the river god angry. You might be convinced not to throw down your weapon and leave your fellow pikemen to face the charge alone either by a love for your comrades-at-arms like that for your brothers, or by knowledge that pikemen who run from charging horsemen get lanced in the back—not to mention what happens to deserters.

Traditionally, religion was the context where society codified and taught its moral rules. The Judeo-Christian tradition has the Ten Commandments, and Buddhism the Four Noble Truths. Muslims have the Five Pillars of Islam. All of these faiths call for the indoctrination of children in their teachings. Religion even exerts a subtle influence on the non-religious. In one experiment, theists and atheists alike gave more money away—to an anonymous stranger, not to charity—when they were first asked to unscramble a jumbled sentence containing words

associated with religion

than when the sentence contained only religion-neutral words. Another found less cheating when they were asked to recall the

Ten Commandments

. A third experiment measured cheating behavior as a function of belief in a deity. They found no difference in cheating behavior between believers and non-believers, but found that people who conceived of a loving, caring, and forgiving God were much more likely to cheat than those who conceived of a

harsh, punitive, vengeful

, and punishing God.

8

Often, morals are not so much prescriptions of specific behaviors as they are meta rules. That is, they are more about intention than action, and rarely dictate actual behaviors. Is the Golden Rule something jurors should follow? Should it dictate how soldiers ought to treat enemy armies? Many ethicists have long argued that the Golden Rule is

pretty much useless

for figuring out what to do in any given situation.

Our moral decisions are contextual. Even something as basic as “Thou shalt not kill” isn't actually all that basic. What does it mean to kill someone? A more modern translation from the original Hebrew is “Thou shalt not murder,” but that just begs the question. What is the definition of murder? When is killing not murder? Can we kill in self-defense, either during everyday life or in wartime? Can we kill as punishment? What about abortion? Is euthanasia moral? Is assisted suicide? Can we

kill animals

? The devil is in the details.

This is the stuff

that philosophers and moral theologians grapple with, and for the most part, we can leave it to them. For our purposes, it's enough to note that general moral reminders are a coarse societal pressure.

Contextualities are everywhere. Prosocial behaviors like altruism and fairness may be universal, but they're expressed differently at different times in each culture. This is important. While morals are internal, that doesn't mean we develop them naturally, like the ability to walk or grasp. Morals are taught. They're memes and they do evolve, subject to the rules of natural selection, but they're not genetically determined.

Or maybe some are. There's a theory that we have a

moral instinct

that's analogous to our language instinct. Across cultures and throughout history, all moral codes have rules in common; the Golden Rule is an example.

Others relevant

to this book include a sense of fairness, a sense of justice, admiration of generosity, prohibition against murder and general violence, and punishment for wrongs against the community. Psychologist and animal behaviorist Marc Hauser even goes so far as to propose that humans have

specific brain functions

for morals, similar to our language centers.

9

And psychologist Jonathan Haidt proposes

five fundamental systems

that underlie human morality.

- Harm/care systems

. As discussed in Chapter 3, we are naturally predisposed to care for others. From mirror neurons and empathy to oxytocin, our brains have evolved to exhibit altruism. - Fairness/reciprocity systems

. Also discussed in Chapter 3, we have natural notions of fairness and reciprocity. - In-group/loyalty systems

. Humans have a

strong tendency

to divide people into two categories, those in our group (“us”) and those not in our group (“them”). This has serious security ramifications, which we'll talk about in the section on group norms later in the chapter, and in the next chapter about group membership. - Authority/respect systems

. Humans have a tendency to

defer to authority

and will follow orders simply because they're told to by an authority. - Purity/sanctity systems

. This is probably the aspect of morality that has the least to do with security, although patriarchal societies have used it to police all sorts of female behaviors. Mary Douglas's

Purity and Danger

talks about how notions of

purity and sanctity

operate as stand-ins for concepts of unhealthy and dangerous, and this certainly influences morals.

You can think of these systems as moral receptors, and compare them to taste and touch receptors. Haidt claims an evolutionary basis for his categories, although the evidence is scant. While there may be an innate morality associated with them, they're also strongly influenced by culture. In any case, they're a useful partitioning of our moral system, and they all affect risk trade-offs.

These five fundamental systems are also influenced by external events.

Spontaneous cooperation

is a common response among those affected by a natural disaster or other crisis. For example, there is a marked

increase in solidarity

during and immediately after a conflict with another group, and the U.S. exhibited that solidarity after the terrorist attacks of 9/11. This included a general

increase in prosocial

behaviors such as spending time with children, engaging in religious activities, and donating money.

Crime in New York

dropped. There was also an increase in

in-group/out-group

divisions, as evidenced by an

increase in hate crimes

against Muslims and other minorities throughout the country.