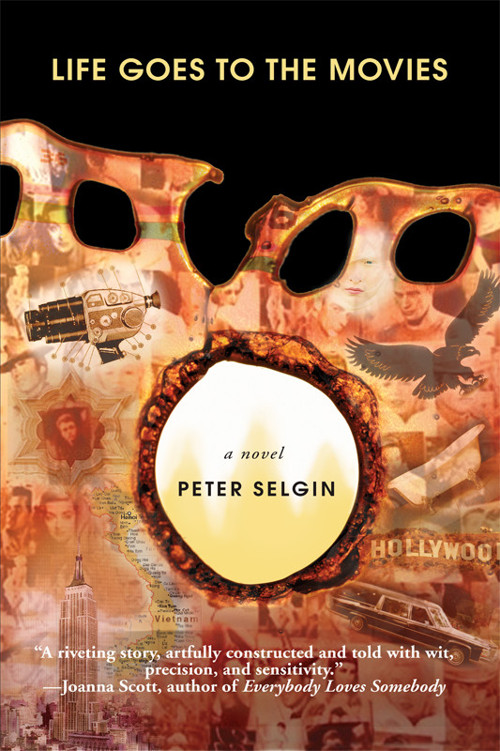

Life Goes to the Movies

Read Life Goes to the Movies Online

Authors: Peter Selgin

a novel

PETER SELGIN

1334 Woodbourne Street

1334 Woodbourne Street

Westland, MI 48186

Copyright © 2011, Text by Peter Selgin

All rights reserved, except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews. No part of this book

may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publisher.

Published 2011 by Dzanc Books

A Dzanc Books r

E

print Series Selection

eBooksISBN-13: 978-1-936873-84-5

Printed in the United States of America

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or

dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

for Paulette

“God’s will be done,” said Sancho. “I’ll believe all your worship says; but straighten yourself a bit in the saddle, for you seem to be leaning over on one side, which must be from the bruises you received in your fall.”

This is a love story.

There’s no other way to describe it.

I’m taking your advice, Brother Joseph:

I’m writing everything down.

I

Blacken

the

Space

(Art Film)

“We didn’t exactly believe your story,

Mrs. O’Schaughnessy,”

—Humphrey Bogart, The Maltese Falcon

The Pertinent Movie Quote Wall

W

e were blackening pages, all of us, covering them with charcoal, leaving no traces of white showing, turning them as black as Con Edison smoke, as

abandoned subway station platforms and third rail rats. As black as the vacuum-packed blackness between stars.

According to Professor Crenshaw there was no such thing as the color white. The air that we breathed was black. What we in our barbaric ignorance

thought of as white was in fact an invisible broth of gloomy matter, light turned inside-out, darkness illuminated.

“Do you see this piece of paper?”Crenshaw’s P’s popped, his crab-eyes bristled.

“This piece of paper is pure, it is pristine, it is virginal! I want you to desecrate it! Rape, plunder, and pillage it with your filthy

black charcoal sticks!”

The figure model, a skinny bored-looking redhead, posed on her carpeted wooden platform, oblivious of the dazzling white tampon string that, in

defiance of Professor Crenshaw’s theories, dangled from her rusty pubic bush. Professor Crenshaw, meanwhile, waving his blank newsprint sheet

like a bullfighter’s cape, leapt through clouds of charcoal dust, yelling:

“Blacken the space! Blacken the space!”

2

That’s when I notice him, standing there by the window, smoking a cigarette, blowing smoke out through the cracked casement. I’ve never

seen him before, at least I don’t remember seeing him. He must be a mid-year transfer student, or maybe he just hasn’t been coming to

Crenshaw’s class. My eyes follow his as they gaze out across the winter campus, over grimy buildings and grim brownstones, past the blue rusting

dinosaur-like cranes of the Navy Yard (still decked out in Bicentennial bunting), over the frozen East River, at the island of Manhattan, a gray

battleship sunk to its gunwales.

So far I’ve blackened a dozen newsprint sheets, rubbing fingertips to bone. Talking is prohibited: no sound but the steadyscrape scrape scrape of charcoal on penny paper and the hum of the electric heater squatting at the nude model’s feet. Jimmy Carter is

President, Abe Beame is Mayor. Pay phones cost a dime. Postage stamps need to be licked. A subway token is still a brass coin with a Y-shaped hole in

the center, and will set you back fifty cents. New York City is broke, lawless, bohemian, dissolute and dangerous.

It’s winter, 1977, but in Professor Crenshaw’s Rudimentary Figure Drawing Class it’s always winter, a black winter of carbon

snow. Ghost cauliflowers bloom in front of our faces as we scratch away in scarves, sweaters, coats and jackets, mine a frayed checkered black and red

hunting jacket hot off the half-price rack at Cheap Jack’s Vintage Clothing store, like the one Marlon Brando wears in On the Waterfront.

Marlon’s my hero, the latest in a long line of TV and movie heroes stretching back to second grade when, in emulation of my then-hero Soupy

Sales, on the playground, during recess, having gathered witnesses, I smashed a shaving cream pie in my own face.

“Blacken the space!”

The smoking guy reminds me a bit of Brando, not the flabby-assed Marlon of Last Tango or The Godfather,but the young Marlon ofStreetcar and On the Waterfront. He’s got the same flattened brow and high, bulbous forehead, its skin stretched shiny by whatever

lurks whale-like under the bone. His lips are thinner, though, more like Jimmy Cagney’s, and he’s got a Gary Cooper squint to his eyes. His

skin is dark, darker than my Italian skin: swarthy, I guess you could call it. There’s something altogether dark about him, what exactly I

can’t say, but it’s darker than this sheet of paper I’ve just finished covering with charcoal. But of all his parts that forehead is

most impressive, so big it seems to charge ahead of the rest of him into the world. The eyes may be Gary Cooper’s; the wavy dark hair may be John

Garfield. But the forehead … the forehead is absolutely Brando.

“Blacken the space! Blacken the space!”

Done smoking, he smashes his cigarette out against a cracked pane, walks back to his drawing horse and, with his left hand, picks up a charcoal stick.

But instead of blackening pages, like we’re supposed to, he draws what look to me from across the charcoal-dusty studio like a series of

rectangles. Within the rectangular panels the same hand whips up a storm of crosshatchings from which human figures emerge.

Suddenly Professor Crenshaw looms over him. Maybe it’s these useless old radiators pinging and hissing up a storm, but I can’t hear a word

as Crenshaw chews him out—as least I assumeCrenshaw is chewing him out, though I can’t say for sure, this being a scenemit oud zound. But I see Crenshaw’s nostrils flaring and his chapped lips pulling back against his teeth and his purple tongue flailing

and his crab eyes bristling as flecks of spittle land on that high swarthy forehead.

Having torn the sheet from the smoking student’s pad, Crenshaw rips it to pieces, then tosses the bits into the air, where they fall like

confetti or snow. The smoking student stands there, expressionless, a soldier being branded. He keeps standing there that way as Crenshaw moves on to

terrorize the next student.

After a beat or two he picks up his charcoal stick and starts sketching again, his left arm swinging loose and free, slicing a dozen deft strokes

across his pad. Done, he picks up the duffel bag stowed under his drawing horse. With it hoisted on his shoulder and leaving the sketchpad behind he

walks out the door.

The rest of us put down our charcoal sticks, and, one by one, step over to see what he’s drawn. Our eyes are met not by a picture, but by words:

SCORSESE

RULES

3

After class I found him in the snack bar. The snack bar’s official name was the Pi Shop, as in the ratio of the circumference of a circle to its

diameter, but everyone called it the Pie Shop, as in apple pie. The heat wasn’t working down there either. My breath hung clouds in front of my

face.

Other students huddled in tight cliques, talking Dada, Duchamp, DeKooning, pissing away their parents’ stock portfolios, filling the frigid air

with artistic bonhomie and acrid smoke from their tipless Gaelic cigarettes. Not the new guy. He sat alone at a far table, as far away from everyone

else as possible. He wore no jacket, just a white shirt with the collar torn off, and a thin black vest, as if his solitude came with its own private

heating supply. Between puffs of a Newport he scribbled away in a black hardbound notebook. He was like some foreign country you’re afraid to

visit because you don’t speak the language. I bought two cups of hot chocolate, screwed up my courage and plopped myself down right in front of

him.

“My name’s Nigel,” I said, sitting. “Nigel DePoli. We’re in the same drawing class. Or we were, anyway.”

I hold out my hand. He keeps on scribbling away in his notebook, ignoring me like I’m not even there. Still not looking up from his scribbling,

he says, “Really? Gee, I could have sworn you were Terry Malloy.” Flattening his already flat brow, squeezing his nostrils together, he

does a perfect Marlon Brando. Chahlie, Chahlie, you was my bruddah, you shoulda looked aftuh me. My cheeks swell with warm fresh blood. Seeing me blush

he smiles a sudden smile that eats up the whole bottom part of his face, his teeth glaringly bright compared to his skin and eyes, which are dark gray

with bits of paler gray floating around like aluminum shards in them. One of his front teeth, I notice, is a shade darker than the others, a soldier

out of step.

“Dwaine Fitzgibbon,” he says, shaking my hand. His grip feels warm and friendly. “That’s D for Death, W for War, A for Anarchy,

I for Insane, N for Nightmare, and E for the End of the World. Pleased to meet you.”

(Dwaine, also Dwain or Dwayne or Dewayne or Duane or Duwain or Duwayne or Dwane: an Anglicized form of the Gaelic “Dubhn” or

“Dubhan,” which can mean “swarthy” or “black” or “little and dark and mysterious.”)

4

He wears one of those traditional Irish rings, two silver hands embracing a heart of gold. He asks my name again and I tell him. “Nigel?DePoli?” He makes a face like he smells something funny. “How did your parents ever come up with a combination like that?”

“It was my father’s idea,” I explain. “His invention, I guess you could say. My father”—I’ve trained myself

never to say ‘my Papa’—“is an inventor. He invents machines for measuring color, texture and thickness, for quality control

purposes, you know, to make sure Batch # such-and-such of Whip ‘n’ Chill is the same color and consistency as Batch # so-and-so.”

Dwaine nods. “He’s an Anglophile,” I continue. “He loves all things English, from Chiver’s coarse-cut orange marmalade to

underpowered cars with terrible electrical systems. You’d never guess he was born in Italy,” I say.

“You’re right,” he agrees. “I’d never guess.”

I don’t add that my father is sixty-five years old, or that he pedals a rusty Raleigh three-speed to the post office and back in black socks that

come all the way up to his knees and a frayed deerstalker cap. Nor am I inclined to mention that the neighborhood kids all shout, “Hey,

Sherlock!” or “Hey, Mr. Magoo!” whenever he passes them by. I’m even less disposed to confess to how much I can’t stand

my own name, how given a choice I would gladly trade it in for Bob or Joe or Tim or even Fred or Frank—any plain, All-American sounding name,

only I don’t have a choice. Well, I do, but I won’t exercise it out of an irrational fear of hurting my dear old papa’s feelings:

irrational since dear old papa is so absentminded and egocentric he would probably never notice.

“What about your father?” I change the subject. “What does he do?”

Dwaine blows a smoke ring that swims jellyfish-like up to the ceiling where it obliterates itself. “My father,” he says slowly with no

inflection at all in his voice, “is a drunken black Irish son of a goddamn bitch.” He smiles. “I’ll take that hot chocolate

now, if it’s still up for grabs.”

I hand him the hot chocolate. In exchange he offers me a cigarette. I tell him I don’t smoke. He nods as if that’s very reasonable of me,

then smiles again as if being reasonable is, well, ridiculous.

5

He said he was a filmmaker. I was into movies myself. Not making them, but watching them, old black-and-white ones especially.Best Year of Our Lives, Birdman of Alcatraz, A Night to Remember, The Train. “I haven’t declared my major yet,” I volunteered.

“Though I was thinking of going into advertising design and production, with maybe a minor in painting or illustration. So what are some of your

favorites? Movies, that is?”

But he’s not listening. He’s too busy framing me with his thumbs. “You’ve got a good face,” he says.

“I do?”

“A touch of DeNiro; a hint of Pacino. Ever acted before?”