Life in a Medieval Castle (19 page)

Read Life in a Medieval Castle Online

Authors: Joseph Gies

At another Round Table in 1256, held at Blyth, the seventeen-year-old Prince Edward fought in armor of linen cloth and with light weapons; but the meeting, like the mass melees, ended in turmoil, with the participants beaten and trampled on. According to Matthew Paris, a number of nobles, including Earl Marshal Roger Bigod of Chepstow, “never afterwards recovered their health.” Prince Edward, as Edward I, sought to regulate rather than ban tournaments and Round Tables. His statute of 1267 aimed at preventing riots by limiting the number of squires and specifying the weapons carried by knights, squires, grooms, footmen, heralds, and spectators. At Edward’s own royal tourneys, there were no casualties.

In France the melee gave way to the joust even earlier. Tournaments of the later type are depicted by the authors

of the romances as brave and colorful pageants. In the

Castellan of Coucy

, the heralds appeared at an early hour to awaken the many guests who had arrived at the castle:

Mass sung and the ladies installed in the pavilions, the jousts began without delay. The first was between the Duke of Limbourg and a bachelor named Gautier de Soul, who broke three lances apiece without losing the stirrups…The seventh was one of the most powerful shows of arms and the most pleasant to see: the first champion wore a sleeve [a token of his lady] on his right arm, and when he went to his station, the heralds cried, “Coucy, Coucy, the brave man, the valiant bachelor, the Castellan of Coucy!” Against him appeared successively Gaucher of Chatillon and Count Louis of Blois…Two more jousts took place; then night fell and the assembly separated to La Fère and Vendeuil…The next day the jousts continued [until] only three knights were left, the others all being wounded…At the first pass the Castellan knocked down his adversary’s helmet into the dust, and blood ran from his mouth and nose…On the third try both men were disarmed and fell unconscious to the ground. Valets, sergeants and squires laid them on their shields and carried them from the field…But it was only, thank God, a passing unconsciousness; neither man was dead. Everyone thanked God and the saints.

Then the Sire de Coucy invited the knights and ladies to dine…More than twenty tents were set up between the Oise and the forest, in fields full of flowers. The Sire de Coucy and all the Vermandois were dressed in green samite studded with golden eagles; they came to the tents leading by the finger the ladies of their country. The men of Hainaut and their ladies were dressed in gold embroidered with black lions; they arrived singing, two by two. The Champenois, the Burgundians, the men of Berri, were also in uniform, scarlet samite decorated with golden leopards.

The tournament gave an impetus to one of the best-known traditions of feudalism and knighthood—the art of heraldry, which took its name from the fact that tournament

heralds became experts in the design of heraldic devices. Symbols on banners and shields to distinguish leaders in the melee of a feudal battle were common as early as the eleventh century. The Bayeux Tapestry shows such devices for both Harold and William. In the twelfth century the custom grew of passing on the device from father to son, like the shield with the golden lions which Geoffrey of Anjou received at his knighting from his father-in-law, Henry I, an emblem inherited by Geoffrey’s grandson William Longespée, earl of Salisbury. Another early device was that of the Clare family, lords of Chepstow; in about 1140 Gilbert de Clare adopted three chevrons, similar to those later used in military insignia. The Clare arms appeared on the lord’s shield, and probably flew from Chepstow to signal the owner’s presence in his castle. Crests, in the form of three-dimensional figures—a boar, a lion, a hawk—were added to the helmet as early as the end of the twelfth century.

In the thirteenth century, the functional value of the heraldic device, or coat of arms, as it came to be called from its use on surcoats, was strongly reinforced as chivalric ideology became popular and affluence encouraged the decorative arts. Even more important was its character as a badge of nobility, visually setting its owner apart from the common people (although wealthy townsmen continued to acquire knightly status and coats of arms to authenticate it). From art, heraldry progressed to become a science, with its own rigid rules and its own jargon. Shields could be partitioned into segments only in certain specified ways, such as

tierced in fesse

(divided into three horizontally) or

in saltire

(cut into four portions by a diagonal cross). Dragons, lions, leopards, eagles, fish, and many other animals, including mythological ones, were used, besides stars, moons, trees, bushes, flowers, and other objects both natural and man-made. The addition of a motto came into fashion, like the French kings’

Montjoye

, the rallying cry and

standard of Charlemagne in the

Chanson de Roland.

All the elements of the arms—crest, helmet, shield, and motto—were finally assembled in a standardized form of heraldic device.

A custom of English nobles that may date to the thirteenth century, that of hanging their heraldic banners outside inns where they were staying, led to the inn sign of later times: the White Hart from the badge of Richard II, the Swan from that of the earls of Hereford, the Rose and Crown from the badge of England.

In the thirteenth century the institution of knighthood, closely related to the life of the castle, was perhaps at its zenith. Already, in fact, signs of decadence were evident in the growing sophistication of attitudes. The

Chanson de Roland

, written at about the time of the First Crusade, and in which the word “chivalrous” makes its first appearance, breathes a spirit of rugged Christian naiveté. Roland brings disaster on Charlemagne’s rear guard by refusing to sound his horn and let Charlemagne know the Saracens are attacking, because to call for help would be cowardly. “Better death than dishonor,” is Roland’s view. His strategy is simple: “Strike with your lance,” he tells Oliver, “and I will smite with Durendal, my good sword which the emperor gave me. If I die, he who shall inherit it will say: it was the sword of a noble vassal.” Durendal contains in its hilt, among other sacred relics, a scrap of the Virgin’s garment. After a terrific battle in which Saracens are cut down in windrows while the French knights drop one by one, the dying Roland is left alone on the corpse-strewn field, his last thoughts of his two lords. Charlemagne and God, to whom he holds his glove aloft as he expires.

The chivalric ideal of the

Chanson de Roland

, developed and celebrated by the poets of the twelfth century, embraced generosity, honor, the pursuit of glory, and contempt for hardship, fatigue, pain, and death.

But by the thirteenth century it was possible to write a

totally different kind of book on the same theme of crusading against the Saracens. The

Histoire de Saint-Louis

, by the Sieur de Joinville, seneschal of Champagne, presents a striking contrast to

Roland.

The chronicle of the ill-fated crusade of Louis IX to Egypt tells in honest prose a story not dissimilar to that of

Roland

—Christian French knights fighting bravely against heavy odds and in the end nearly all dying. But the difference in tone is vast: Joinville’s knights are real, they suffer from their wounds and disease, and death seems more miserable than glorious. And even though Joinville cherishes and admires the saintly Louis much as Roland loved Charlemagne, his attitude is very different. St. Louis asks Joinville, “Which would you prefer: to be a leper or to have committed some mortal sin?” The honest seneschal reports, “I, who had never lied to him, replied that I would rather have committed thirty mortal sins than become a leper.”

Common sense has intruded on chivalry.

The Castle at War

W

ARFARE IN THE

M

IDDLE

A

GES

centered around castles. The clumsy, disorganized feudal levies, called out for a few weeks’ summer service, rarely met in pitched battles. Their most efficient employment was in sieges, a condition that fitted neatly into the capital strategic value of the castle.

Medieval warfare was not as incessant as some of the older historians have pictured it. The motte-and-bailey stronghold of the ninth and tenth centuries was frequently embroiled, either with Viking, Saracen, and Hungarian marauders or with neighboring barons, but by the eleventh century the marauders had been discouraged and private warfare was on the wane. In England it was outlawed by William the Conqueror and effectively suppressed by his successors. To take its place there were the Crusades, including those against Spanish Moors and French Albigensians; international wars, such as those waged by Richard the Lionhearted, John and Henry III in France,

and the wars of conquest in Wales, Scotland, and Ireland; and civil wars, such as that fought by Stephen of Blois and the Empress Matilda over the throne, and the numerous rebellions of barons against royal authority. Despite all these, many twelfth- and thirteenth-century castles were rarely besieged, and Chepstow was unusual but by no means unique in passing entirely through the Middle Ages without ever seeing an enemy at its gates.

Nevertheless, when war broke out, it inevitably revolved around castles. Enemy castles were major political-military objectives in themselves, and many were sited specifically to bar invasion routes. Typically the castle stood on high ground commanding a river crossing, a river confluence, a stretch of navigation, a coastal harbor, a mountain pass, or some other strategically important feature. The castle inside a city could be defended long after the city had been taken, and an unsubdued castle garrison could sally out and reoccupy the town the moment the enemy left. Even a rural castle could not safely be bypassed, because its garrison could cut the invader’s supply lines. The mobility of the garrison—nearly always supplied with horses—conferred a large strategic radius for many purposes: raiding across a border, furnishing a supply base for an army on the offensive, interrupting road or river traffic at a distance. For all these reasons, medieval military science was the science of the attack and defense of castles.

The castle’s main line of resistance was the curtain wall with its projecting towers. The ground in front of the curtain was kept free of all cover; if there was a moat, the ground was cleared well beyond it. Where the approach to the castle was limited by the site, and especially where it was limited to one single direction, the defenses on the vulnerable side multiplied, with combinations of walls, moats, and towers masking the main curtain wall. At Chepstow the eastern end was protected by the Great

Gatehouse, with its arrow loops, portcullises, and machicolations. The barbican built by the Marshals to protect the western end consisted of a walled enclosure a hundred feet wide by fifty deep, with a powerful cylindrical tower at the southwest corner and a fortified gatehouse on the northwest. The barbican was separated from the west curtain wall by a broad ditch, or dry moat, crossed by a bridge with a draw span and overlooked by a strong rectangular tower on the inner side. The ditch ended at the south wall in an inconspicuous postern which, even if forced, would admit the enemy only to a trap, enfiladed by the towers and the wall parapet. The long sides of the castle had strong natural defenses: the river with its high bluff on the north, and the steep slope of the ridge on the south toward the town.

Such a castle as Chepstow was practically proof against direct assault, while its size provided ample facilities for storing provisions. Some castles kept a year’s supply of food or even more on hand, and the relatively small size of a thirteenth-century garrison often meant that in a prolonged siege the assailants rather than the besieged were confronted with a supply problem. A garrison of sixty men could hold out against an attacking force ten times its number, and feeding sixty men from a well-stocked granary supplemented by cattle, pigs, and chickens brought in at the enemy’s approach might be far easier than feeding 600 men from a war-ravaged countryside.

By the late thirteenth century, castle logistics were on a sophisticated basis, with supplies often purchased from general contractors, such as the consignments ordered from one John Hutting in June 1266 to supply the castle of Rochester, used as a base by Henry III’s general Roger Leyburn: 251 herrings, 50 sheep, 51 salted pigs, and quantities of figs, rice, and raisins. More commonly a single commodity was bought from an individual merchant or group of merchants; for Rochester, Roger Leyburn bought fish from merchants of Northfleet and Strood; oats from

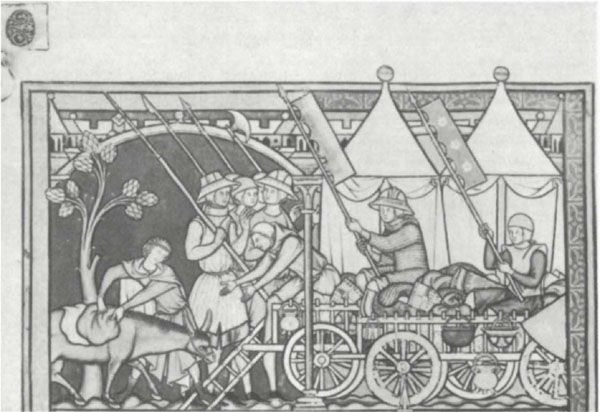

Military provision carts carrying helmets and hauberks, cooking pots hung along the sides. (Maciejowski Bible, Pierpont Morgan Library. MS. 638, f. 27v)

Maidstone, Leeds, and Nessindon; rye from a merchant of Colchester, and wine from Peter of London and Henry the Vintner of Sittingbourne.

A castle’s water supply frequently offered a more vulnerable target than its food supply. Although a reliable well, in or near the keep, was one of the basic necessities of a castle, wells sometimes failed, and when they did the results were disastrous. In the First Crusade, when the Turks besieged the Crusaders in the castle of Xerigordo near Nicaea and cut off their water supply, the beleaguered Christians suffered terrific hardships, drinking their horses’ blood and each other’s urine, and burying themselves in damp earth in hope of absorbing the moisture. After eight days without water the Christians surrendered, and were killed or sold as slaves. Two decades later Count Fulk of Anjou, besieging

Henry I’s castle of Alençon, managed to locate and destroy an underground conduit from the river Sarthe, and the garrison was forced to surrender. In 1136, when King Stephen was besieging a rebellious baron, Baldwin of Redvers, in the castle of Exeter, the castle’s two wells suddenly went dry. The garrison drank wine as long as it lasted, also using it to make bread, to cook, and to put out fires set by the attackers. In the end the rebels yielded, and, in the words of the chronicler of the

Gesta Stephani

, “when they finally came forth you could have seen the body of each individual wasted and enfeebled with parching thirst, and once they were outside they hurried rather to drink a draught of any sort than to discharge any business whatsoever.”

Hunger and thirst aside, no defensive fortification was proof against all attack, and even the strongest castles of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries could be, and were, captured. The castle had few vulnerable points, but what few it had were assiduously exploited by its enemies.

A frequent structural weakness of castles lay in their subsoil. Unless a castle was founded wholly on solid rock, some part of its walls could be undermined by digging. The procedure was to drive a tunnel beneath the wall, preferably under a corner or tower, supporting the tunnel roof with heavy timbers as the sappers advanced. When they reached a point directly under the wall, the timbering was set ablaze, collapsing earth and masonry above. The process was not as easy as it sounds. In 1215, when King John laid siege to Rochester Castle, a vast twelfth-century square keep defended by about a hundred rebel knights and a number of foot soldiers and bowmen, he ordered nearby Canterbury to manufacture “by day and night as many picks as you are able.” Six weeks later the digging had progressed to the point when John commanded justiciar Hubert de Burgh to “send to us with all speed by day and night forty of the fattest pigs of the sort least good for eating

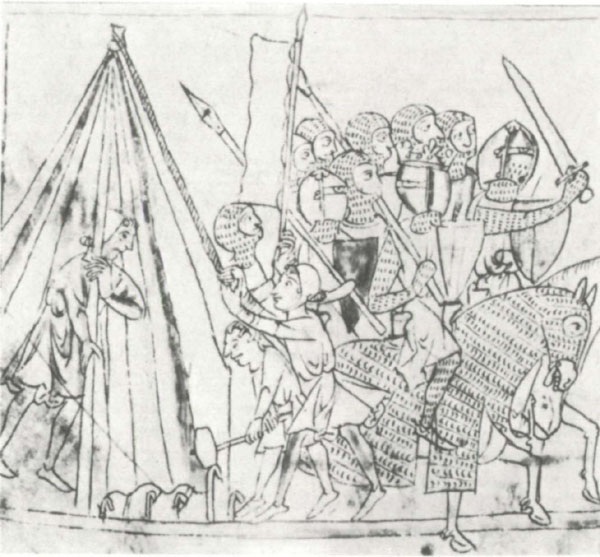

Erecting a tent. On the left, a foot-soldier raises a pole, while another drives in the stakes and a third holds the rope. (Trustees of the British Museum. MS. Lans. 782, f. 34v)

to bring fire beneath the tower.” The lard produced a sufficient blaze in the mine to destroy the timbering and bring down a great section of the wall of the keep.

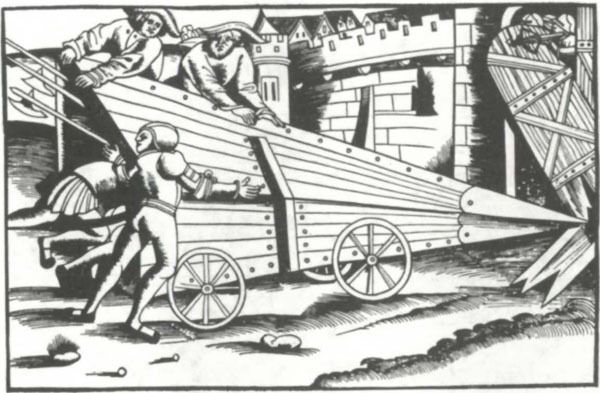

A castle built on a solid rock foundation, such as Chepstow, had to be attacked with two other main devices inherited by medieval military engineers from ancient predecessors: the mobile assault tower and the siege engine or catapult artillery. The assault tower, usually called a cat, but sometimes a bear or other figurative term, was normally assembled from components brought to the site. The aim of all the many designs was to provide the storming party with cover and height, neutralizing the advantages of the

defenders. The tower might be employed to seize a section of the rampart or to provide cover for sappers or a battering ram. The immense gates of the powerful castles of the High Middle Ages were rarely forced by ramming, though a small castle might be vulnerable to the heavy beam or tree trunk, fronted with an iron or copper head (sometimes literally a ram’s head), either grasped directly by its crew or swung from leather thongs. Before any form of direct assault, the moat defense had first to be dealt with, usually by filling it in with brush and earth. The assault tower, containing both archers and assault troops to engage the defenders hand-to-hand, could then be wheeled forward to the castle wall. A large besieging army could build and man several such towers and by attacking different points of the wall exploit its numerical advantage. Since the towers were wooden, the castle’s defenders tried to set them afire by hurling torches or fire-bearing arrows.

Medieval engineers used the ancient tension and torsion engines, in the commonest form of which a tightly wound horizontal skein, its axis parallel to the wall under attack, was wound still tighter by an upright timber arm fixed to its shaft at right angles, and drawn back to ground level. The timber arm, or firing beam, now under great tension, was charged with a missile at its extreme end and released. At the upright position the arm’s leap forward was halted by a padded crossbar, causing the missile to fly on. Data on ranges are scarce, but modern experiments have achieved a distance of 200 yards with 50-pound rocks.

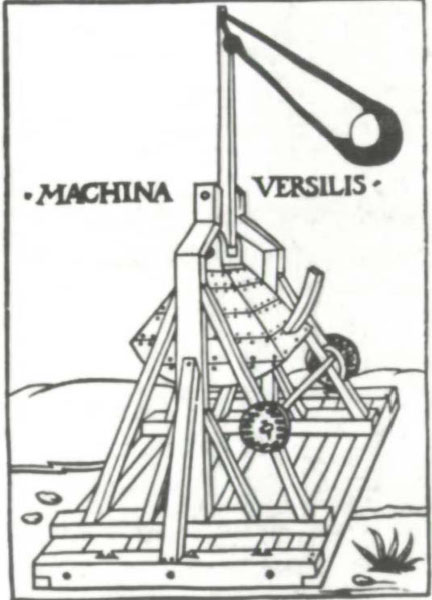

Medieval engineers devised another form, the trebuchet, driven by a counterweight, an invention also used for castle drawbridges. The Arabs had used a catapult in which the beam was pulled down by a gang of men and released. European military engineers introduced a decisive improvement. In the trebuchet, the firing beam was pivoted on a crosspole about a quarter of its length from its butt end, which was pointed at the enemy castle. The butt end was

A battering ram.

A trebuchet.