Life in a Medieval Castle (20 page)

Read Life in a Medieval Castle Online

Authors: Joseph Gies

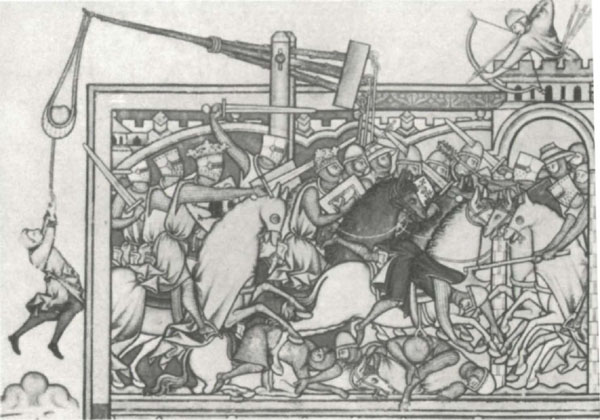

weighted with a number of measured weights calibrated for range, and the long end, pulled down by means of a winch, was loaded with the missile. Released, the beam sprang to the upright position, discharging the missile with a power and accuracy said to be superior to that of the tension and torsion engines. First used in Italy at the end of the twelfth century, the trebuchet was widely employed in the Albigensian Crusade of the early 1200s. It made its appearance

Battle scene from the thirteenth-century Maciejowski Bible. Top left, loading a trebuchet; adjustable counterweights are hidden behind the melee at the center of the picture. (Pierpont Morgan Library. MS. 638, f. 23v)

in England in 1216 during the siege of Dover by Prince Louis of France. The following year a trebuchet was carried on one of Louis’s ships when his fleet, attempting to enter the mouth of the Thames, was decisively defeated in the battle of Sandwich; the machine weighed down the ship “so deep in the water that the deck was almost awash,” and proved a handicap rather than an advantage in the encounter. The effectiveness of the trebuchet in a siege was formidable, however, because of its capacity to hit the same target repeatedly with precision. In 1244 Bishop Durand of Albi designed a trebuchet for the siege of Montségur that hurled a succession of missiles weighing forty kilograms (eighty-eight pounds) at the same point in the wall day and

night, at twenty-minute intervals, until it battered an opening.

Ammunition of the attackers included inflammables for firing the timber buildings of the castle bailey. The effectiveness of stone projectiles depended on the height and thickness of the stone walls against which they were flung. The walls of the early twelfth century could be battered down, and often were. The result was the construction of much heavier walls—in Windsor Castle, for example, reaching a thickness of twenty-four feet.

Defenders of large castles used artillery of their own for counter-battery fire. During Edward I’s Welsh wars, an engineer named Reginald added four

springalds

(catapults) to the towers of Chepstow, one mounted on William Fitz Osbern’s keep. Trebuchets and mangonels, mounted on the towers or even on the broad walls of castles, hurled rocks, frequently the besiegers’ own back at them, with the additional advantage gained from height.

A different principle—that of the crossbow—supplied another form of artillery for both besiegers and besieged. The ancient Roman ballista, easy to mount on castle walls, discharged a giant arrow, or quarrel. The smaller crossbow was the basic hand-missile weapon of besiegers and besieged throughout the Middle Ages. Used but apparently not appreciated by the Romans, the crossbow mysteriously disappeared for several centuries before its reintroduction into Europe, probably in eleventh-century Italy. In the First Crusade it proved a novelty to both Turks and Byzantine Greeks. Apparently a new, stronger trigger mechanism was responsible for the crossbow’s resurgence. In the form best known in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, it was cocked by means of a stirrup at the end of the stock, or crosspiece. Placing the weapon bow down, so that the stock was in a vertical position, the archer engaged the stirrup with his foot while hooking the bowstring to his belt.

He pushed down with his foot to cock the bow, which was caught and held by a trigger mechanism. Unhooking the string from his belt, the archer raised the weapon and fired by squeezing a lever under the stock. A range of up to 400 yards was attainable. The crossbow was exceptionally well suited to castle defense, for which the Welsh-English longbow, effective on the open battlefield, was less successful. The longbow had a shorter range and shot a lighter missile, and its greater portability and rapid rate of fire were of less account in castle defense than on the battlefield.

The chronicle

Annals of Dunstable

gave a vivid description of the capture of Bedford Castle, seat of the unruly lord Falkes de Bréauté, by the forces of Henry III in 1224, in an arduous eight-week siege. Falkes’ castle consisted principally of two stone towers, an old and a new, separated by an inner bailey and surrounded by a broad outer bailey with a gate defended by a strong barbican.

On the eastern side was a stone-throwing machine and two mangonels which attacked the [new] tower every day. On the western side were two mangonels which reduced the old tower. A mangonel on the south and one on the north made two breaches in the walls nearest them. Besides these, there were two wooden machines erected…overlooking the top of the tower and the castle for the use of the crossbowmen and scouts.

In addition there were very many engines there in which lay hidden both crossbowmen and slingers. Further, there was an engine called a cat, protected by which underground diggers called miners…undermined the walls of the tower and castle.

Now the castle was taken by four assaults. In the first the barbican was taken, where four or five of the outer guard were killed. In the second the outer bailey was taken, where more were killed, and in this place our people captured horses and their harness, corselets, crossbows, oxen, bacon, live pigs and other things beyond number. But the buildings with grain and hay in them they burned. In the third assault,

thanks to the action of the miners, the wall fell near the old tower, where our men got in through the rubble and amid great danger occupied the inner bailey. Thus employed, many of our men perished, and ten of our men who tried to enter the tower were shut in and held there by their enemies. At the fourth assault, on the vigil of the Assumption, about vespers, a fire was set under the tower by the miners so that smoke broke through into the room of the tower where the enemy were; and the tower split so that cracks appeared. Then the enemy, despairing of their safety, allowed Falkes’ wife and all the women with her, and Henry [de Braybroke], the king’s justice [whose capture by Falkes’ brother William had caused the siege], with other knights whom they had shut up before, to go out unharmed, and they yielded to the king’s command, hoisting the royal flag to the top of the tower. Thus they remained, under the king’s custody, on the tower for that night.On the following morning they were brought before the king’s tribunal, and when they had been absolved from their excommunication by the bishops, by the command of the king and his justice they were hanged, eighty and more of them, on the gallows.

At the prayers of the leaders the king spared three Templars, so that they might serve Our Lord in the Holy Land in their habit. The chaplain of the castle was set free by the archbishop for trial in an ecclesiastical court…

Falkes himself took the cross and was allowed to leave the country and go to Rome. The castle was dismantled except for the inner bailey, where living quarters were left for the Beauchamp family, earls of Bedford; the stones of the towers and outer bailey were given to local churches (poetic justice, since they had been built with the stones of two churches pulled down for that purpose by Falkes).

Garrisons surrendering at discretion were not usually so harshly dealt with. In ordinary conflict, without the added passion of religious difference or rebellion against authority, the whole garrison might be spared. Or the knights might

be ransomed and the foot-soldiers massacred or mutilated. Often a rebel castle surrendered before it was absolutely necessary, in return for the garrison’s being allowed to depart in freedom.

Even a castle sited on rock, well-provisioned with food and water, and stout-walled against artillery might still be taken by ruse. Usually the ruse was of the Trojan horse variety, that is, designed to effect entry by a small party. A popular trick was the nocturnal “escalade,” a silent scaling of the wall at an inadequately guarded point. Another was a diversion designed to draw defenders away from a secondary gate or weak point that might then be suddenly overwhelmed. A third was penetration by means of a special ingress, such as a mine, a disused well, or a latrine, as in the case of Richard the Lionhearted’s Château Gaillard in 1204. Occasionally the garrison might be lured into a sortie, so that the attackers could penetrate the gates as the defenders fled back into the castle.

Another form of ruse involved disguise. The attacking army might raise the siege and ostentatiously march away, but remain just out of sight. Some of its soldiers, donning the dress of peasants or merchants, might then gain access to the provision-hungry castle and seize the gatehouse. Knights were sometimes smuggled into a castle concealed in wagonloads of grain. The men of Count Baldwin of Flanders rescued their lord from imprisonment in a Turkish castle in 1123 by disguising themselves as peddlers and daggering the gate guards.

The dominant role of the siege helps explain one of the most characteristic aspects of medieval warfare: its stop-and-go, on-again-off-again pattern. Truces were natural between adversaries who might for long periods remain within ready range of communication but safe from each other’s attack. In the war between Prince Louis of France and Henry III, at least five truces were made between

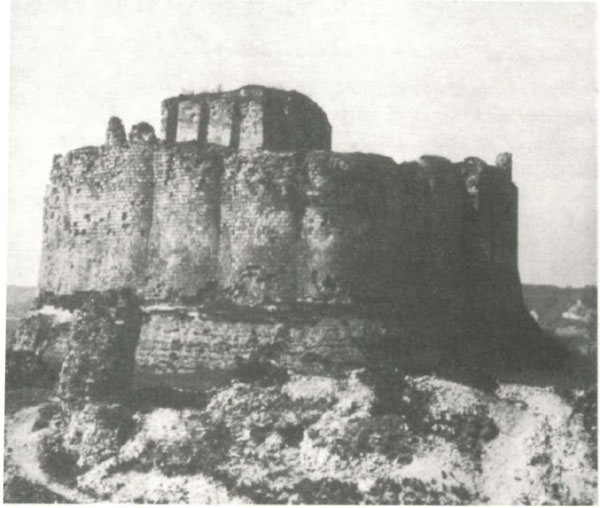

Château Gaillard: The keep of Richard the Lionhearted’s stronghold on the Seine can be seen above the corrugated wall of the inner bailey. (Archives Photographiques)

October 1216 and February 1217, all related to castle sieges.

A shrewd commander besieging a castle might take advantage of a truce to plant a spy or bribe a member of the garrison. He might obtain valuable information, for example on the castle’s supplies, or he might arrange for a postern to be opened at midnight or a rampart to be left unguarded. In 1265, a spy, apparently disguised as a woman, reported to Henry III’s son Edward (later Edward I) that the garrison of Simon de Montfort’s Kenilworth Castle planned to leave the stronghold for the night in order to enjoy baths in the town. According to the

Chronicle of Melrose

, the king’s men surprised Simon’s knights asleep and unarmed, and “some of them might be seen running off

entirely naked, others wearing nothing but a pair of breeches, and others in shirts and breeches only.”

Simon’s son (Simon de Montfort III), in command of the party, regained the castle by swimming the Mere, the castle’s lake, in his nightshirt. His father was killed three days later in the battle of Evesham, and the following spring young Simon had to defend Kenilworth Castle against the royal army. Despite a terrific pounding by siege engines, the castle held out against every assault, beating off a giant cat carrying 200 bowmen, and destroying another with a well-directed mangonel shot. Even the intervention of the archbishop of Canterbury had no effect; when the prelate appeared outside the castle to pronounce excommunication of the garrison, a defender donned clerical robes and jeered from atop the curtain wall. The king offered lenient terms, but Simon turned them down. It was nearly Christmas when Simon, his provisions exhausted, slipped out of the castle with his brothers to escape abroad, permitting his starving and dysentery-ridden garrison to surrender.

Bohemund d’Hauteville captured the powerful Saracen stronghold of Antioch by a combined bribe and ruse. Corrupting Firuz, an emir who commanded three towers, with promises of wealth, honor, and baptism, he had his own Frankish army feign withdrawal. That night the Franks returned stealthily and a picked band scaled the walls of Firuz’ sector, killed resisting guards, and opened the gate. By morning the city was in the hands of Bohemund, who true to knightly tradition, even in a Crusade, had already extracted a promise from his fellow barons that the whole place would be turned over to him.

The chronicler of the

Gesta Stephani

related with relish the story of a ruse that was worked on Robert Fitz Hubert, one of the barons who rebelled against King Stephen and “a man unequaled in wickedness and crime,” at least according to the partisan historian. Fitz Hubert took Stephen’s Devizes Castle by a night escalade and then refused to turn

it over to the earl of Gloucester, on whose side in the civil war he was supposed to be fighting. But Fitz Hubert came a cropper in negotiating with a neighbor baron, none other than John Fitz Gilbert the Marshal, father of William Marshal, whom the chronicler describes as “a man equally cunning and very ready to set great designs on foot by treachery.” John had seized Marlborough, a strong castle belonging to the king. Fitz Hubert sent word to John that he would make a pact of peace and friendship, and that he wanted to parley with him at Marlborough. John agreed, but after admitting him to the castle behaved characteristically; he shut the gates behind him, “put him in a narrow dungeon to suffer hunger and tortures,” then handed him over to the earl of Gloucester, who took him back to his own castle of Devizes and hanged him in sight of the garrison. The knights of the garrison then accepted a bribe and turned over the castle to the earl of Gloucester.