Life in a Medieval Castle (7 page)

Read Life in a Medieval Castle Online

Authors: Joseph Gies

In the thirteenth century the castle kitchen was still

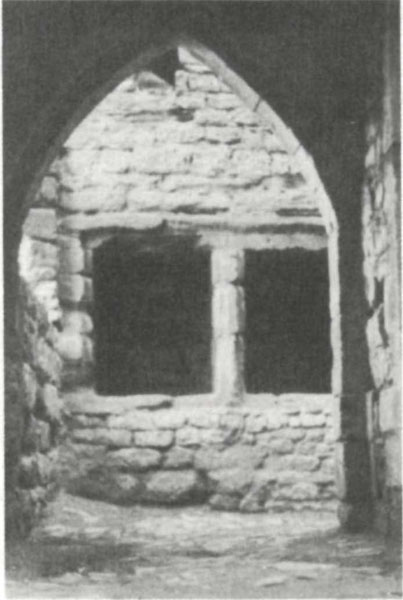

Chepstow Castle: Cupboards built into the wall of the passageway between the Great Hall and the Lesser Hall of the thirteenth-century domestic range.

generally of timber, with a central hearth or several fireplaces where meat could be spitted or stewed in a cauldron. Utensils were washed in a scullery outside. Poultry and animals for slaughter were trussed and tethered nearby. Temporary extra kitchens were set up for feasts, as for the coronation of Edward I in 1273 when a contemporary described the “innumerable kitchens…built” at Westminster Palace, “and numberless leaden cauldrons placed outside them, for the cooking of meats.” The kitchen did not normally become part of the domestic hall until the fifteenth century.

In the bailey near the kitchen the castle garden was usually planted, with fruit trees and vines at one end, and plots for herbs, and flowers—roses, lilies, heliotropes, violets, poppies, daffodils, iris, gladioli. There might also be a fishpond, stocked with trout and pike.

Both the interior and exterior stonework of medieval castles were often whitewashed. Interiors were also plastered,

paneled, or ornamented with paintings or hangings. Usually these interior decorations, like most of the comforts of the castle, began with the dais area of the hall, often the only part to be wainscoted and painted. A favorite embellishment was to paint a whitewashed or plastered wall with lines, usually red, to represent large masonry blocks, each block decorated with a flower. The queen’s chamber at the Tower of London in 1240 was wainscoted, whitewashed, given such sham “pointing” or “masoning,” and painted with roses. Wainscoting was of the simplest kind, vertical paneling painted white or in colors. In England the wood was commonly fir imported from Norway. In the halls of Henry III’s castles, the color scheme was frequently green and gold, or green spangled with gold and silver, and many of the chambers were decorated with murals: the hall at Winchester with a map of the world, a lower chamber at Clarendon with a border of heads of kings and queens, an upper chamber with paintings of St. Margaret and the Four Evangelists and, as described in the king’s building instructions, “heads of men and women in good and exquisite colors.” Wall hangings of painted wool or linen that were the forerunners of the fourteenth-century tapestries were not merely adornments, but served the important purpose of checking drafts.

In the earliest castles the family slept at the extreme upper end of the hall, beyond the dais, from which the sleeping quarters were typically separated only by a curtain or screen. Fitz Osbern’s hall at Chepstow, however, substituted for this temporary division a permanent wooden partition. In the thirteenth century William Marshal’s sons removed the partition, making the old chamber part of the hall. They constructed a masonry arcade to support a new chamber above, with access by a wooden stair. In the last decade of the thirteenth century the new third-story chamber was extended over the entire hall.

The Great Hall of the domestic range at Chepstow had

its own chamber on the floor above, while the Lesser Hall was equipped with a block of chambers at the upper end, on three levels. Sometimes castles with ground-floor halls had their great chamber, where the lord and lady slept, in a separate wing at the dais end of the hall, over a storeroom, matched at the other end, over the buttery and pantry, by a chamber for the eldest son and his family, for guests, or for the castle steward. These second-floor chambers were sometimes equipped with “squints,” peepholes concealed in wall decorations by which the owner or steward could keep an eye on what went on below.

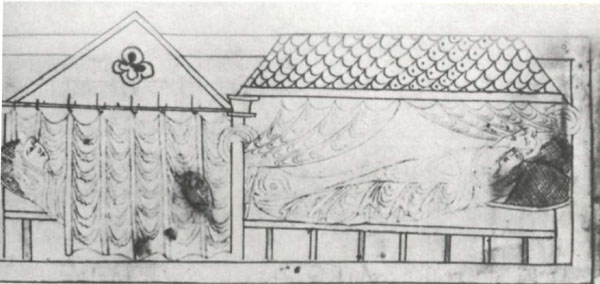

The lord and lady’s chamber, when situated on an upper floor, was called the solar. By association, any private chamber, whatever its location, came to be called a solar. Its principal item of furniture was a great bed with a heavy wooden frame and springs made of interlaced ropes or strips of leather, overlaid with a feather mattress, sheets, quilts, fur coverlets, and pillows. Such beds could be dismantled and taken along on the frequent trips a great lord made to his other castles and manors. The bed was curtained, with linen hangings that pulled back in the daytime and closed at night to give privacy as well as protection from drafts. Personal servants might sleep in the lord’s chamber on a pallet or trundle bed, or on a bench. Chests for garments, a few “perches” or wooden pegs for clothes, and a stool or two made up the remainder of the furnishings.

The greatest lords and ladies might occupy separate bedrooms, the lady in company with her attendants. One night in 1238, Henry III of England had a narrow escape, reported by Matthew Paris, when an assassin climbed into his bedchamber by the window, knife in hand, but found him not there. “The king was, by God’s providence, then sleeping with the queen.” One of the queen’s maids, who was awake and “singing psalms by the light of a candle.” saw the man and alerted the household.

Sometimes a small anteroom called the wardrobe adjoined

Curtained beds. (Trustees of the British Museum. MS. Claud. B.iv, f. 27v)

the chamber—a storeroom where cloth, jewels, spices, and plate were stored in chests, and where dressmaking was done.

In the thirteenth century, affluence and an increasing desire for privacy led to the building of small projecting “oriel” rooms to serve as a secluded corner for the lord and his family, off the upper end of the hall and accessible from the great chamber. Often of timber, the oriel might be a landing at the top of external stairs, built over a small room on the ground floor. It usually had a window, and sometimes a fireplace. In the fourteenth century, oriels expanded into great upper-floor bay windows. An example for an extraordinary purpose was added to Stirling Castle during the siege by Edward I in 1304 in order to provide the queen of Scotland and her ladies with a comfortable observation post.

In the early Middle Ages, when few castles had large permanent garrisons, not only servants but military and administrative personnel slept in towers or in basements, or in the hall, or in lean-to structures; knights performing castle guard slept near their assigned posts. Later, when castles were manned by larger garrisons, often of mercenaries,

separate barracks, mess halls, and kitchens were built.

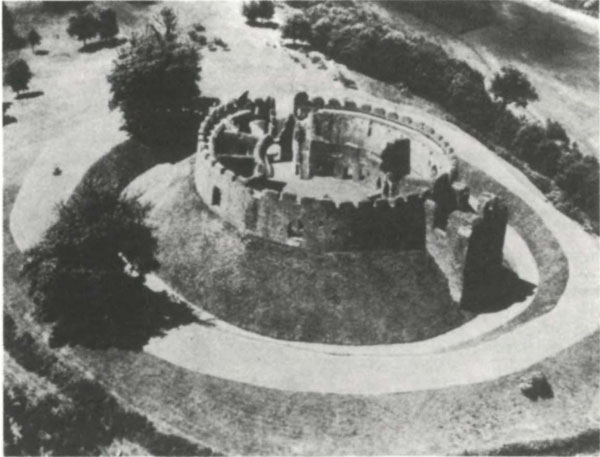

An indispensable feature of the castle of a great lord was the chapel where the lord and his family heard morning mass. In rectangular hall-keeps this was often in the forebuilding, sometimes at basement level, sometimes on the second floor. By the thirteenth century, the chapel was usually close to the hall, convenient to the high table and bed chamber, forming an L with the main building or sometimes projecting opposite the chamber. A popular arrangement was to build the chapel two stories high, with the nave divided horizontally; the family sat in the upper part, reached from their chamber, while the servants occupied the lower part.

Except for the screens and kitchen passages, the domestic quarters of medieval castles contained no internal corridors. Rooms opened into each other, or were joined by spiral

Restormel Castle, Cornwall: Twelfth-century shell keep with domestic buildings and barracks added in thirteenth century around inside of wall, with a central court. Projecting building at right is the chapel. (Department of the Environment)

staircases which required minimal space and could serve pairs of rooms on several floors. Covered external passageways called pentices joined a chamber to a chapel or to a wardrobe and might have windows, paneling, and even fireplaces.

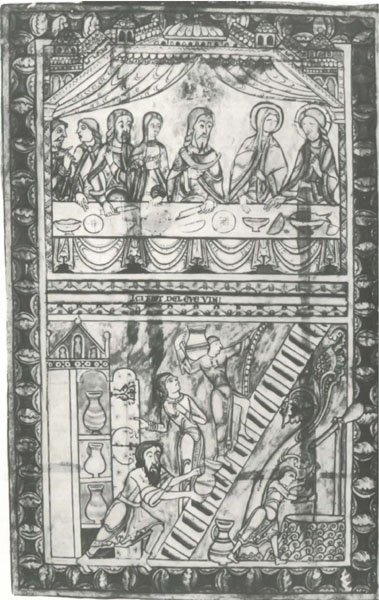

Water for washing and drinking was available at a central drawing point on each floor. Besides the well, inside or near the keep, there might be a cistern or reservoir on an upper level whose pipes carried water to the floors below. Hand washing was sometimes done at a laver or built-in basin in a recess in the hall entrance, with a projecting trough. Servants filled a tank above, and waste water was carried away by a lead pipe below, inflow and outflow controlled by valves with bronze or copper taps and spouts.

Baths were taken in a wooden tub, protected by a tent or canopy and padded with cloth. In warm weather, the tub was often placed in the garden; in cold weather, in the chamber near the fire. When the lord traveled, the tub accompanied him, along with a bathman who prepared the baths. In some important thirteenth-century castles and palaces there were permanent bathrooms, and in Henry III’s palace at Westminster there was even hot and cold running water in the bath house, the hot water supplied by tanks filled from pots heated in a special furnace. Edward II had a tiled floor in his bathroom, with mats to protect his feet from the cold.

The latrine, or “garderobe,” an odd euphemism not to be confused with wardrobe, was situated as close to the bed chamber as possible (and was supplemented by the universally used chamber pot). Ideally, the garderobe was sited at the end of a short, right-angled passage in the thickness of the wall, often in a buttress. When the chamber walls were not thick enough for this arrangement, a latrine was corbeled out from the wall over either a moat or river, as in the domestic range at Chepstow, or with a long shaft reaching nearly to the ground. This latter arrangement

In a scene from the story of the Marriage at Cana, servants draw water from a well with a dipping beam. (Trustees of the British Museum. MS. Nero Civ, f. 17)

sometimes proved dangerous in siege, as at Château Gaillard, Richard the Lionhearted’s castle on the Seine, where attackers obtained access by climbing up the latrine shaft. As a precaution, the end of the shaft was later protected by a masonry wall. Often several latrines were grouped together into a tower, sometimes in tiers, with a pit below, at the angle of the hall or solar, making them easier to clean. In some castles rainwater from gutters above or from a cistern or diverted kitchen drainage flushed the shaft.

Henry III, traveling from one of his residences to another, sent orders ahead:

Since the privy chamber…in London is situated in an undue and improper place, wherefore it smells badly, we command you on the faith and love by which you are bounden to us that you in no wise omit to cause another privy chamber to be made…in such more fitting and proper place that you may select there, even though it should cost a hundred pounds, so that it may be made before the feast of the Translation of St. Edward, before we come thither.