Life in a Medieval Castle (2 page)

Read Life in a Medieval Castle Online

Authors: Joseph Gies

Either because of the rocky site or the strategic location, or both, Fitz Osbern determined to build his castle of stone. The rectangular keep that rose on the narrow ridge above the Wye was consequently one of the strongest in Norman England, its menacing bulk suggesting not merely a barrier to contain the Welsh but a base for aggression against them.

Dover Castle: Rectangular keep built in the 1180s. (Department of the Environment)

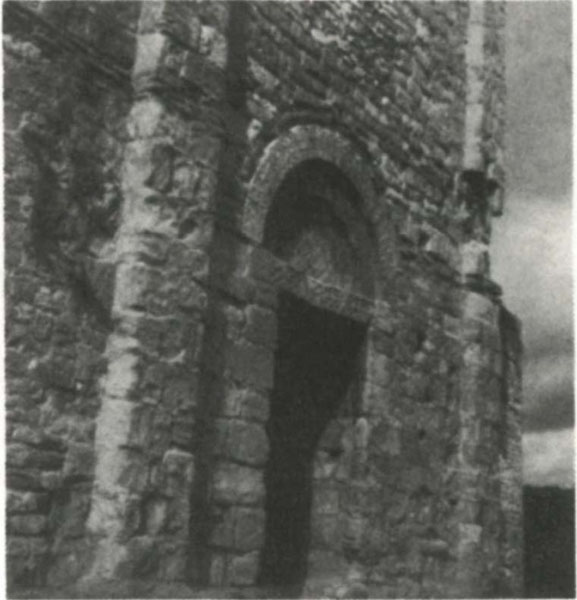

Chepstow Castle: Entrance to the Great Tower, with round-headed doorway decorated with Norman sawtooth carving. Below, the Great Tower from the east. The River Wye is on the right, while the towers of the barbican can be seen beyond and to the left. (Department of the Environment)

Chepstow was one of the few Anglo-Norman castles not sited to command an important town. Sometimes instead of a city causing a castle to be built, the reverse was true, as craftsmen and merchants settled close by for protection and to serve the castle household. One English example of such a castle-originated city is Newcastle-on-Tyne, which grew up around the stronghold built by William the Conqueror’s son Robert to command the Tyne crossing. Several of the chief cities of Flanders were castle-derived: Ghent, Bruges, Ypres.

By 1086, when at William’s orders the elaborate survey of his conquered territory known as

The Domesday Book

was compiled, the iron grip of the invading elite was beyond shaking. Only two native Englishmen held baronies as tenants-in-chief of the king in the whole of England from Yorkshire south. English chronicler William of Malmesbury commented, “Perhaps the king’s behavior can be excused if he was at times quite severe with the English, for he found scarcely any of them faithful. This fact so irritated his fierce mind that he took from the greater of them first their wealth, then their land, and finally, in some instances, their lives.”

William died the following year, 1087, bequeathing to his elder son, Robert, the rich old domain of Normandy, and to his younger son, William Rufus, the family’s new realm of England. But though the English were now docile under their immense bridle of castles, the castles were now showing another aspect. Unchallenged centers of local power, they corrupted the loyalty of their Norman owners, who threw off their feudal obligations to assert the rights of petty sovereigns. In 1071 loyal William Fitz Osbern had been killed fighting in Flanders and his estates divided between his sons, the younger, Roger de Breteuil, inheriting his father’s English lands, including Chepstow Castle. In 1074 Roger and his brother-in-law, the Breton Ralph de Guader, earl of Norfolk, had organized a rebellion, “fortifying

their castles, preparing arms and mustering soldiers.” King William crushed this rebellion of his Norman followers like so many previous English outbreaks, and made an effort to conciliate its leaders. To the captive lord of Chepstow he sent an Easter box of valuable garments, but sulky Roger threw the royal gifts into the fire. Roger was then locked up for life and Chepstow Castle confiscated.

By the turn of the twelfth century the half dozen English castles of 1066 had grown to the astounding number of more than five hundred. Most were of timber, but over the next century nearly all were converted to masonry as a revolution in engineering construction swept Europe. New techniques of warfare and the increasing affluence of the resurgent West, giving kings and nobles augmented revenues from taxes, tolls, markets, rents, and licenses, brought a proliferation of stone fortresses from the Adriatic to the Irish Sea.

A major contributor to the sophistication of the new castles was the extraordinary event known to the late eleventh century as the Crusade, and to subsequent generations as the First Crusade. Of the peasants and knights who tramped or sailed to the Holy Land and survived the fighting, most soon returned home. The defense of the conquered territory was therefore left to a handful of knights—primarily the new military brotherhoods, the Templars and the Hospitallers. Inevitably their solution was the same as that of William the Conqueror, but the castles they built were from the start large, of complex design, and of stone. The Crusaders made use of the building skills of their sometime Greek allies and their Turkish enemies, improved by their own experience. The results were an astonishing leap forward to massive, intricately designed fortresses of solid masonry. The new model of castle spread at once to western Europe, including England.

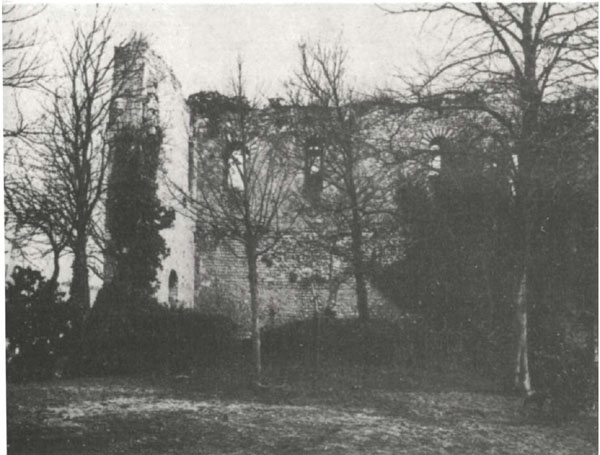

Langeais: Ruins of the rectangular keep built on the Loire by Fulk Nerra of Anjou around

A.D.

1000, the earliest stone keep extant in northern Europe. (Archives Photographiques)

On the Continent, even before the Crusade, where conditions were favorable, powerful keeps were sometimes built of stone, like that constructed by Fulk Nerra at Langeais on the Loire about

A.D.

1000 or Brionne Castle in Normandy (early eleventh century), or like the keeps built by the Normans after their conquest of southern Italy and Sicily in the eleventh century. The baileys that accompanied such stone keeps were probably defended by timber stockades. Between the Conquest and the Crusade a few stone castles appeared in England.

Some of the new structures were conversions of motte-and-bailey castles to “shell keeps” by the erection of a stone wall to replace the timber stockade atop the motte. Within

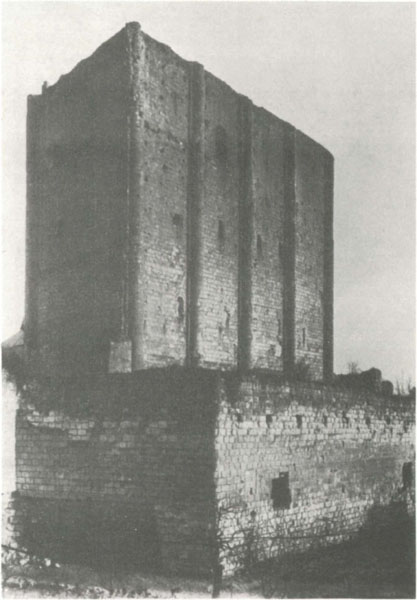

Loches: Rectangular keep built about 1020, on the Indre River, France. (Archives Photographiques)

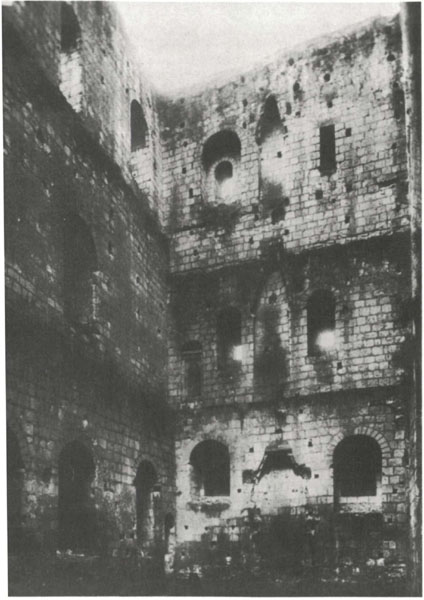

Loches, interior of rectangular keep. (Archives Photographiques)

this new stone wall, living quarters were built, usually of timber, either against the wall to face a central courtyard or as a free-standing tower or hall.

In many cases the mound was too soft to support a heavy stone wall, and the new stronghold had to be erected on the lower, firmer ground of the bailey. These new keeps were usually rectangular in plan. Sometimes they were built on high or rocky ground, but site was still not a significant factor. All over northern France in the eleventh century new rectangular stone keeps rose on low or high ground, while in England William Fitz Osbern’s castle at Chepstow was joined by the White Tower of London and the keeps at Canterbury and Colchester. The old wooden palisades of the bailey were now replaced by a heavy stone “curtain wall,” made up of cut stone courses enclosing a rubble core and “crenelated,” that is, crowned with battlements of alternating solid parts (merlons) and spaces (crenels), creating a characteristic square-toothed pattern. The curtain wall was further strengthened with towers.

In the twelfth century rectangular stone keeps continued to multiply—in England at Dover, Kenilworth, Sherborne, Rochester, Hedingham, Norwich, Richmond, and elsewhere, with thick walls rising sixty feet or more. Usually entrance was on the second story, reached by a stairway built against the side of the keep and often contained in and protected by a forebuilding. The principal room, the great hall, was on the entrance floor, with chambers opening off it; the ground floor, windowless or with narrow window slits, was used for storage. A postern or alternate gate, protected by towers, frequently opened on another side of the curtain. A well, often descending to a great depth, was an indispensable element of a keep, its water pipe carried up through two or three floors, with drawing places at each floor.

Gradually experience revealed a disadvantage in the rectangular keep. Its corners were vulnerable to the sapper.

Gisors, Normandy: Early twelfth-century shell keep built on an artificial motte 45 feet high, with a four-story octagonal tower added by Henry II of England.