Living Silence in Burma (22 page)

Read Living Silence in Burma Online

Authors: Christina Fink

Soon after, the state media announced that the 1990 election results were no longer valid. Whether the NLD would be allowed to participate in the elections, which were scheduled for 2010, was unclear. The USDA began preparing to set up proxy parties to run in the 2010 elections, however, and cultivating businessmen who would be willing to run as candidates. If the elections go ahead as scheduled, pro-regime parties are likely to take a share of the vote, and with the

tatmadaw

representatives holding 25 per cent of the seats, it will be difficult for other parties to have much influence. The implementation of the constitution will lead to a division of power at the top, however, with the president appointing the commander-in-chief of the defence services. Whether Than Shwe will take the job of president or finally retire is unclear.

Meanwhile, Aung San Suu Kyi continued to be held under house arrest without ever being charged with committing a crime. According to the regime’s laws, a person can be held for five years without being charged. In Aung San Suu Kyi’s case, 30 May 2008 marked the fifth anniversary of her detention, but she was not released. When Ibrahim Gambari, the UN Special Envoy, visited Burma for the fourth time in two years in August 2008, Aung San Suu Kyi refused to meet with him, apparently out of frustration with the lack of any political progress.

The regime wanted to keep Aung San Suu Kyi under detention during the planned 2010 election in order to prevent the re-emergence of a dynamic and united opposition movement. In May 2009, they found a pretext for doing so. On 3 May 2009, a fifty-three-year-old American man named John Yettaw secretly swam across Inya Lake to her house with the hope of talking with her. He had made a previous attempt in late 2008, but Aung San Suu Kyi refused to meet with him. She later asked her doctor to inform the authorities about the incident. When John Yettaw arrived the second time, Aung San Suu Kyi again asked him to leave, but he begged for some food and time to rest, saying he was exhausted. He was arrested on his swim back across the lake early on the morning of 5 May.

On 11 May 2009, the authorities charged Aung San Suu Kyi with violating the terms of her house arrest, as foreigners are not allowed to visit her compound. She was moved to Insein Prison, and informed that she could be imprisoned for up to five years for her ‘crime’. Despite the international outcry, the trial proceeded in a closed courtroom at the prison. Her lawyers argued that she was innocent, as Yettaw was an intruder, not an invited guest. Yettaw claimed in court that he had felt compelled to journey to her compound because he believed she was going to be assassinated and needed to warn her. When this book was finished, she had not yet been sentenced and the authorities had not accepted responsibility for failing to provide adequate security around her compound.

In conclusion, the regime seemed to be fully in control, although not because it had any legitimacy in the eyes of its people. Those who witnessed the brutal crackdown on the September 2007 demonstrations were seething inside, while increasing access to the Internet and outside media, and increasing travel abroad, had made many people realize that few governments in the world were as cruel and incompetent as theirs. Many people sought a better life abroad while others tried to do what they could to make the country a better place.

1 Farmers transplanting rice in Rangoon Division, 1996

2 A procession of boys who are about to be ordained as novice monks and their relatives, Thaton, Mon State, 2000

3 A Karenni mass in a refugee camp on the Thai–Burma border, 2007

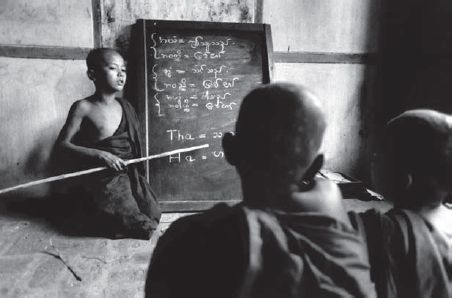

4 Novice monks studying in a monastery near Mandalay, 1996

5 Aung San Suu Kyi speaking from her gate, 1996

6 Armed Forces Day parade in Naypyidaw, 2007

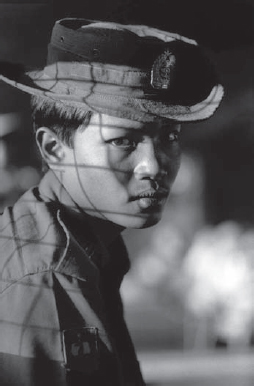

7 A young Burmese soldier at a train station in Kachin State, 1998

8 A policeman watching monks walk by in Nyaung Shwe, Shan State, 2005

6 | Families: fostering conformity

We’re always acting, saying what we think the authorities want to hear. It’s so exhausting. (A pastor)

Individuals in Burma often talk and act in seemingly contradictory ways. When they sense that the political atmosphere is more relaxed, they complain openly about the regime or voice their support for Aung San Suu Kyi and the pro-democracy movement. During periods of greater repression, however, they tend to stay silent or even criticize democracy activists as ineffective. At moments when the democracy struggle seems to have no chance of success, some people even dismiss its validity, as they seek to make peace with their lives under military rule.

Similarly, the public may enjoy reading critiques of the regime or watching movies that indirectly parody military rule, but when family members or neighbours are the ones acting against the government, they may find they have little support. This is because the authorities have been known to harass and arrest the family members and close friends of activists, even if they have done nothing against the regime themselves. By punishing those who surround activists, the authorities can isolate them and discourage activism from spreading. Thus, as much as relatives and neighbours might admire those who are courageous enough to act for change, they can be reluctant to offer any direct support.

The following chapters look more closely at how families, communities and professional groups are torn between protecting themselves and standing up for what they believe. Under military rule in Burma, it seems that doing what is right is often directly opposed to doing what is necessary to survive. As the military’s influence has seeped into virtually every aspect of people’s lives, resistance becomes difficult to imagine. Yet, there are dynamic individuals who have tried to reclaim certain activities, such as education, social work, art and religious practice, from military control or to fend off military involvement.

Collective amnesia