Long-Ago Stories of the Eastern Cherokee (6 page)

Read Long-Ago Stories of the Eastern Cherokee Online

Authors: Lloyd Arneach

The Nunnehi lifted up the townhouse with its mound to carry it away. They were surprised by the screaming and let some of it drop to the ground. They recovered, and took the rest of the townhouse, with the people in it, to Lone Peak. Today, near the head of the Cheowa River, there is a huge rock. This is the townhouse with the people in it that was changed long ago into solid rock. The people are inside of it, invisible and immortal.

There was another town where the people also prayed and fasted. This was on the Hiwassee River, near where Shooting Creek flows into it. At the end of seven days the Nunnehi took the people down into the waters. It is said that on a summer's day, when the wind blows across the water, if you have good hearing and listen quietly, you can hear the people talking under the water. When the Cherokee fish the deep water in this area, their lines will stop and they know it is their fellow tribesmen who are holding the line and do not want to be forgotten.

At the time of the Removal in 1838, the Cherokee who lived along the Valley and Hiwassee Rivers were especially grief-stricken, for they were also forced to leave their relatives who had gone to the Nunnehi.

S

EQUOYAH

A long time ago, the Cherokee saw the white man doing many things that they had never seen before. They would see a white man open up what looked like a leaf. He would look at it and know what another white man far away had said. At first the Cherokee did not know what they were doing. We did not have a word for “letter.” The closest thing we had that looked like a letter was a leaf, and because whoever read the leaf knew what someone else far away had said, the “leaf” talked. We called letters “talking leaves.”

There was one man of our people who decided to try and duplicate the “talking leaves” of the white man. He was a skilled silversmith, but had suffered an injury that left him lame. He studied our language and found that we had eighty-six separate and distinct sounds. He started writing down symbols for each of the sounds. Using the English alphabet for symbols, he quickly ran out of letters to use.

His people made fun of him and told him he couldn't make the things of the white man. His wife was always after him to do some silverwork to help bring in food for the family. It was a very difficult time for him. One day, after he had been working on the symbols for several years, he was out of the cabin and his wife took everything he had been working on and threw it in the fireplace. He came home, saw what his wife had done and said, “Gosh darn it! I wish you hadn't done that!”

Since we don't have any curse words in our language he was very limited in what he could say. Once again, he started working with the symbols.

Finally the alphabet was finished. He took it to his tribal council and showed them that it worked. The council adopted his alphabet as the official written language of the Cherokee. The man's name was Sequoyah. If you spoke the Cherokee language, all you had to do was learn what symbol stood for what sound. In two to three weeks a person could read and write in Cherokee. It did not matter what came before the symbol or what came after; it was always pronounced the same. Because it is written, our language will never die out. Sequoyah could not read or write in any language. He took another culture's model and made it a reality for his people.

T

HE

S

MOKY

M

OUNTAINS

Before Selfishness came into the world a long time ago, the Cherokee were happy using the same hunting and fishing lands as their neighbors. But all this changed when Selfishness came into the world and men began to quarrel.

The first quarrel of the Cherokee was with a tribe from the east. Finally, the chiefs of the two tribes met in council to settle the quarrel. They smoked the pipe and quarreled for seven days and seven nights.

The Great Spirit was displeased because people are not supposed to smoke the pipe until they make peace. As He looked down on the old men sitting with their heads bowed, He decided to do something to remind all people to smoke the pipe only when making peace.

The Great Spirit turned the old men into grayish flowers, which we now call “Indian Pipes,” and made them grow wherever friends and relatives have quarreled. He made the smoke hang over the mountains until all people all over the world learn to live together in peace.

S

PEARFINGER

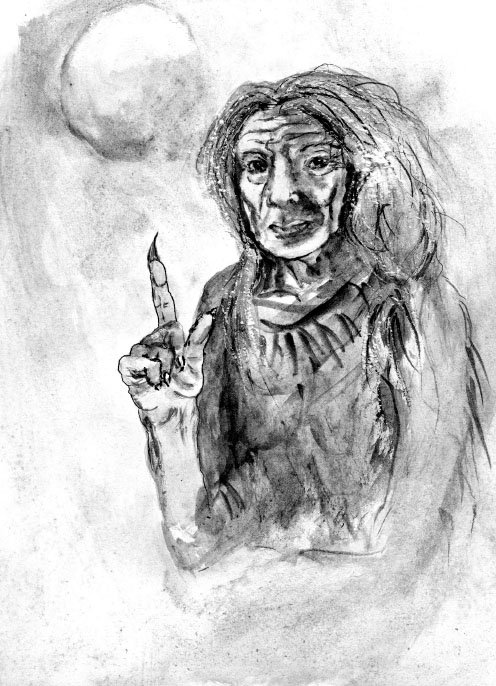

We had monsters in our culture. Some of these were shape-shifters, or those who could change their shapes to look like anybody they wanted to. This shape-shifter looked like a little old lady in her normal shape. Her skin looked like regular skin, but it was as hard as stone. Arrows would hit her and bounce off; spears would hit her and break. She could change her entire shape except for her right index finger. This finger was a little longer than normal. This was how she got her name: “Spearfinger.” She was a monster because she lived on human livers. She always kept her finger hidden with a robe over her right wrist, or a basket over her right wrist and her finger hidden down in the basket so no one could see it.

If she could get close to people she would stab them with her finger and they would seem to go to sleep. She would open the bodies, take out the livers and cause the bodies to heal up. In a little while the people would wake up. They would feel no pain and wouldn't know what had happened. In a few days, they would take sick and die. Everyone would know that Spearfinger had taken their livers.

Spearfinger was always roaming the woods looking for her next meal. If she saw young people in the woods, she might say, “Come here little ones. I have some honey in this basket and you can eat it while I comb your hair.” If the children had been properly trained by their parents not to talk to strangers in the woods, they would run away.

In the fall of the year, the Cherokee would burn the leaves off the mountains to get at the nuts underneath. When Spearfinger saw the smoke rising into the sky, she would know the Cherokee were out on the mountains and she had a chance for another meal. When someone went into the woods by himself, the others never knew if the person coming back was the same one or if it was Spearfinger who had taken his shape.

Spearfinger killed so many of the Cherokee that finally they held a great council. All of the Wise Men and Warriors met for days trying to figure out a way to stop Spearfinger. After a long while they came up with a plan they thought would work.

They made sure all the people stayed in their villages, and then the Warriors went far back into the mountains. They selected a path that led far back into the Great Smoky Mountains. They dug a deep pit and covered it with branches and leaves so it looked like a part of the path. They built a large fire by the side of the path and hid themselves in the bushes.

Spearfinger looked out of her lair from far back in the Great Smoky Mountains and saw the smoke. She started down the path, looking for another meal. She carried her basket over her right wrist.

Soon the Warriors heard someone coming down the path singing a song. Around a bend in the path came a little old woman with a basket over her right wrist. They quietly watched as she walked down the path and stepped out on the branches. The branches broke and dropped her into the pit. When Spearfinger hit the bottom of the pit, she jumped to her feet and started screeching and yelling and clawing at the side of the pit.

The Warriors quickly surrounded the pit and looked down on Spearfinger. When Spearfinger looked up and realized that it was the Cherokee who had tricked her, she became more enraged and clawed even harder at side of the pit. The Warriors realized she would be able to claw her way out of the pit in a short while. They started shooting arrows and throwing their spears down at her.

The arrows would bounce off and the spears would break when they hit her. Spearfinger laughed and told them what she would do to them when she got out of the pit. Then a little bird flew over the pit and sang a song that sounded like the Cherokee word for heart. They took this as a sign to aim at her heart. Again, the arrows bounced off and the spears broke.

They caught the bird and clipped his tongue. The Cherokee know this bird as a liar. When it sings near a home it doesn't mean a loved one is coming home. Then another bird flew down into the pit and landed on Spearfinger's right hand next to her index finger. They took this as a sign to aim at her right hand. When they did, they saw Spearfinger's face change from anger and rage to fear and terror because her heart was contained in the palm of her right hand and she always kept her right fist tightly closed to protect it.

Finally, an arrow struck her at the base of her index finger and she fell over dead. And that is the story of Spearfinger.

T

HE

T

RAIL

OF

T

EARS

In the late 1820s gold was discovered in north Georgia near a town called Dahlonega. At that time, the Cherokee were living in north Georgia. It was thought that there was more gold on Cherokee lands. The governor of Georgia was trying to get the Cherokee moved out of Georgia, and he asked the government in Washington for help. Andrew Jackson was president at the time. He signed into law the Indian Removal Act, which called for the removal of all of the Indians who lived east of the Mississippi to the West.

White settlers started moving onto Cherokee lands. They claimed the land for themselves and started charging Cherokee rent for their own land. The Cherokee appealed to the state of Georgia for help and the governor refused to help them. They then turned to the Department of Justice in Washington for help. The U.S. Supreme Court Justice Marshall ruled that Georgia was wrong and that U.S. government troops should be sent in to help the Cherokee.

President Jackson refused. He said, “Justice Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it!” No U.S. troops were sent in.

The Cherokee refused to move to the West. The government in Washington sent in an Indian agent, whose specialty was getting treaties signed by Indian tribes. He was called Reverend Schermerhorn. His assignment was to get a treaty signed by the Cherokee agreeing to move to the West. He went among the Cherokee telling them that the Great White Father in Washington wanted to give them all of this level land west of the Big Muddy, which is what we called the Mississippi. They wouldn't have to try and farm the steep mountainsides anymore. They needed to come to a meeting at New Echota, Georgia, and sign a piece of paper to get their land.

The Cherokee leaders realized what Schermerhorn was trying to do. They went among their people telling them not go to this meeting. They tried to tell them that they didn't know what Schermerhorn was really trying to get them to do. But, as always, there was a small group of people who did not listen. This group went to the meeting and signed their names to the paper.

Schermerhorn immediately sent the paper to Washington. Cherokee Chief John Ross left for Washington also. He talked to everyone who would listen. He told them that the majority of his people did not sign this paper, that none of their major leaders had signed the paper and that it had been signed by only a handful of people who didn't know what they were signing.

But the paper was sent to the U.S. Senate and they voted to accept it as being signed by the Cherokee Nation by only one vote. When word reached the Cherokee that the treaty had been accepted, a group of Cherokee immediately left for Indian Territory in Oklahoma. The rest stayed where they were.

Six months passed, and then a year passed, and nothing happened. The Cherokee thought Washington had forgotten about them. Washington was still having trouble with Indians out West.

Then, in the spring of 1838, federal troops showed up in Cherokee country. They built stockades and then started rounding up the Cherokee. The troops learned that if they came in the early morning they could catch all of the family at home before they went out to do their chores. They moved so quickly that a father might have been milking the cow when the troops showed up and he would only have time to turn the cow out into the pasture and grab what he could carry in his hands. Then he and his family would be driven down the trail. Sometimes, before they were taken out of sight of their home, other whites would enter to ransack the house, drive the livestock out of the pasture and set fire to the house.