Love at Goon Park (24 page)

Authors: Deborah Blum

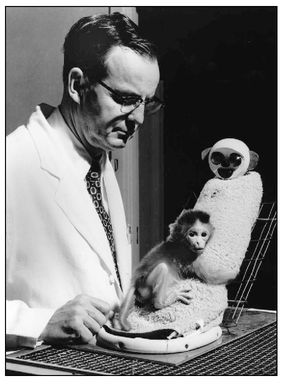

In this 1958 publicity photo, Harry surveys one of his most famous results, the union of cloth mother and a baby monkey in her care.

Photo courtesy of the University of Wisconsin Archives

Photo courtesy of the University of Wisconsin Archives

A baby monkey, in the comforting presence of his cloth mother, decides to tackle a previously frightening toy insect.

Photo courtesy of the Harlow Primate Laboratory, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Photo courtesy of the Harlow Primate Laboratory, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Harry, taking a rare moment to relax, during the late 1960s.

Photo courtesy of the Harlow Primate Laboratory, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Photo courtesy of the Harlow Primate Laboratory, University of Wisconsin-Madison

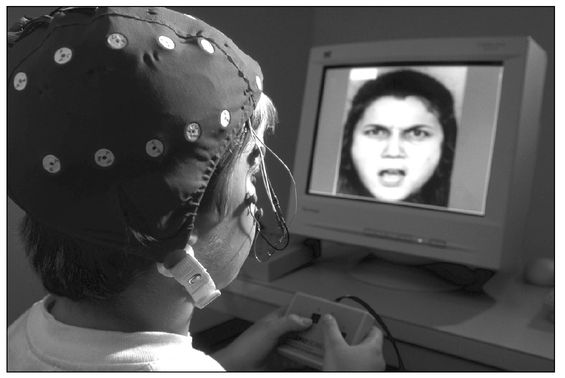

A young boy evaluates an angry face during a recent study of children's emotional relationships at the University of Wisconsin Department of Psychology.

Photo courtesy of University of Wisconsin News and Services

Photo courtesy of University of Wisconsin News and Services

SIX

The Perfect Mother

One cannot ever really give back to a child the love and attention he needed and did not receive when he was small.

John Bowlby,

Can I Leave My Baby?,

1958

Can I Leave My Baby?,

1958

Â

Â

Â

STILL, HARRY DID NOT STEP directly into love; there was no triumphant flourish of research trumpets. In 1955, he had to tackle a different problem, more pragmatic, more urgent. It had to do with importing monkeys: He was beginning to hate that process. The animals were hard to find. They were expensive. They were often in terrible shape. Monkeys routinely turned up starving, battered in passage, seething with “ghastly diseases.” The hot-tempered, tropical viruses spread easily. The incoming macaques infected their cage mates. Playmates sickened alongside monkey playmates. Macaque mothers passed diseases to their infants. A laboratory with a new shipment of monkeys could more easily resemble a hospital than a research laboratory.

Harry began to ponder raising his own animals. It was this decision that would, indirectly, lead him into the science of affection. When it didâwhen he first started wondering whether you can raise a healthy child, even a monkey child, without loveâthe people

working with him would think he'd gone crazy. Of course, they were used to Harry Harlow's crazy ideas. Starting a breeding colony in Madison, Wisconsin, struck plenty of people as evidence enough of lunacy. The Midwestern climate, almost the polar opposite of the balmy seasons of India, seemed an unlikely place to start raising tropical species. But Harry had been accommodating monkeys for many winters. He figured that they'd just continue bundling the monkeys inside. That would keep the colony small, only what he could house indoors. He could live with that.

working with him would think he'd gone crazy. Of course, they were used to Harry Harlow's crazy ideas. Starting a breeding colony in Madison, Wisconsin, struck plenty of people as evidence enough of lunacy. The Midwestern climate, almost the polar opposite of the balmy seasons of India, seemed an unlikely place to start raising tropical species. But Harry had been accommodating monkeys for many winters. He figured that they'd just continue bundling the monkeys inside. That would keep the colony small, only what he could house indoors. He could live with that.

There was another, bigger, challenge. No one really knew how to do what he wanted. There were no self-sustaining colonies of monkeys in the United States. The domestic breeding of primates was a brand new, barely simmering idea. Other people were talking about it; indeed, researchers from California to Connecticut were equally frustrated. But no one had any experience at breeding monkeys on the scale Harry imagined. Only a few American scientists had even tried hand-raising the animals in any systematic way and that had been on a monkey-by-monkey kind of scale. Did this faze Harry? Not really. Once you've built a laboratory out of a box factory, starting a breeding colony from scratch just isn't that big a deal.

Still, he first consulted with his friends at Wisconsin. Harry and his university colleagues decided to approach the problem like the scientists they were. What does one feed a baby monkey? William Stone, from the university's biochemistry department, spent countless hours testing formulas. As he remarked years later, “I can still smell the monkeys as I recall sleeping at the primate lab on a four-hour schedule” to try out different recipes on the baby monkeys. Stone eventually had so much data that he published a paper on the immune effects of feeding cattle serum to newborn monkeys. He began with a baby formula of sugar, evaporated milk, and water. He recruited students to hold doll-sized bottles to feed the monkeys. Every bottle was sterilized. The monkeys received vitamins every day. Their daily doses included iron extracts, penicillin and other antibiotics, glucose, and “constant, tender, loving care.” The baby monkeys

were washed, weighed, and watched over constantly. As the monkeys grew older, lab caretakers mixed fresh fruit and bread into their diet. And always, always, the caretakers kept the animals apart from each other. Every monkey in a separate cage. Every baby taken from his mother, which is why someone needed to hold those baby bottles. Harry wanted no chances taken on the spread of those ghastly diseases. Everything was polished and cleaned and disinfected and wiped to a glittering cleanliness.

were washed, weighed, and watched over constantly. As the monkeys grew older, lab caretakers mixed fresh fruit and bread into their diet. And always, always, the caretakers kept the animals apart from each other. Every monkey in a separate cage. Every baby taken from his mother, which is why someone needed to hold those baby bottles. Harry wanted no chances taken on the spread of those ghastly diseases. Everything was polished and cleaned and disinfected and wiped to a glittering cleanliness.

There was a model for such practices in human medicine, in the frantic efforts of early pediatricians to control disease in orphanages and hospitals. The Wisconsin researchers mimicked perfectly, had they realized it, the very hospital policies that Harry Bakwin had been so furiously trying to undo in the 1940s. Harlow and his colleagues were inadvertently recreating those isolationist pediatric wards.

By the end of 1956, the lab managers had taken more than sixty baby monkeys away from their mothers, tucked them into a neatly kept nursery, usually within six to twelve hours after a monkey's birth. Lab staffers fed the infant animals meticulously, every two hours, with the carefully researched formula from the tiny dolls' bottles. And the monkeys looked good. The little animals gained weight on that formula. They were bigger than usual, heftier and healthier looking. And they were purified of infection, “disease-free without any doubt,” wrote Harry. But their appearance, he added, turned out to be deceptive: “In many other ways they were not free at all.”

The monkeys seemed dumbfounded by loneliness. They would sit and rock, stare into space, suck their thumbs. When the monkeys were older and the scientists tried to bring them together for breeding, the animals backed away. They might stare at each other. They might even make a few tentative gestures, as if each primate vaguely wished to encourage something. But the nursery-raised monkeys had no idea what to do with each other. They seemed startled by the appearance of other animals, intimidated by the sight of such odd, furry strangers. The monkeys were so unnerved by each other that many of them would simply stare at the floor of the cage, refusing to

look up. “We had created a brooding, not a breeding colony,” Harry once commented.

look up. “We had created a brooding, not a breeding colony,” Harry once commented.

How could the monkeys look so healthy and yet be so completely unhealthy in their behavior? The researchers had a growing colony of sturdy, bright-eyed, bizarre animals in their cages. Not all the animals were so unstable. But enough were to keep the researchers up at night. Harry was driven to making lists of possibilities. What was he doing wrong? Could it be the light cycleâwas the lab not dark enough at night? The antibiotics? Perhaps the medicines were skewing normal development. The formula? It might be that evaporated milk wasn't such a good thing. Maybe the baby monkeys were being given too much sugarâor not enough.

Harry and his students and colleagues talked it over as the coffee steamed, the bridge cards shuffled, and the nights burned away in the lab. Harry's research crew was still growing and, on the recommendation of his old professor, Calvin Stone, he'd brought another Stanford graduate into his lab. The latest young psychologist to venture into the box factory was named William Mason. His Stanford Ph.D. barely off the presses, Mason found himself immediately plunged into the problem of the not-quite-right baby monkeys.

Shortly after arriving, Bill Mason was put in charge of raising six newborn animals. These were all lab-made orphans: taken away from their mothers some two hours after birth. In Harry's lab, the monkeys were often given names instead of the numbers that are standard in primate labs today. The oldest of Mason's orphans was Millstone, named by a lab tech because the little monkey was such a noisy, clingy pest. The other five infants also joined the Stone family: Grindstone, Rhinestone, Loadstone, Brimstone, and Earthstone. A research assistant at the lab, Nancy Blazek, had feeding duties. Exhausted by the two-hour schedule, she took to bringing the little monkeys home with her for their nighttime bottles.

Mason and Blazek spent hours with those monkeys, and they got to know them well. They wanted the babies to grow strong and healthy. Mason planned to continue some of the earlier studies on

curiosity. Harry had established that monkeys were naturally curious, and Mason wondered how early that trait showed up. When did monkeys start to wonder about the world around them? Were they born asking questions or did they pick it up later? When it came to puzzles, at least, Mason and Blazek found that the Stone babies were naturals. As soon as they were coordinated enough to work a puzzle, the little creatures were busy trying to solve it. The results reinforced a strong suspicion that curiosity was fundamental to the way these small primates approached the world.

curiosity. Harry had established that monkeys were naturally curious, and Mason wondered how early that trait showed up. When did monkeys start to wonder about the world around them? Were they born asking questions or did they pick it up later? When it came to puzzles, at least, Mason and Blazek found that the Stone babies were naturals. As soon as they were coordinated enough to work a puzzle, the little creatures were busy trying to solve it. The results reinforced a strong suspicion that curiosity was fundamental to the way these small primates approached the world.

Something else about the Stone monkeys caught the lab workers' attention. The researchers had been lining the cages with cloth diapers to provide a little softness and warmth against the floor. All the little monkeys, including those in the Stone family, were absolutely, fanatically attached to those diapers; they not only hugged the diapers fiercely but also wrapped themselves in the white cloth, clutched at it desperately if someone picked them up. Around the lab, an observer might be struck by the appearance of baby monkeys in transit, cloth streaming out behind them like kite tails.

There was already a hint about this cloth-obsession from the nineteenth century, in the diaries of a British naturalist named Alfred Russel Wallace. The adventurous Wallace is best remembered now because he so nearly published a theory of evolution before Charles Darwin. As with Darwin, it was traveling that made the theory come to life. Exploring the oddly different and beautifully adapted species of each country also made Wallace think about the way nature tucks us into our niches. During a visit to Indonesia, Wallace had been given an orphaned baby orangutan. He wrote in his journal that the little animal seemed to constantly reach for and cuddle soft material, including (painfully) Wallace's beard. Trying to help the baby and himself, Wallace made what he called a “stuffed mother” out of a roll of buffalo skin. He noted that the little ape clung happily to the fat, fuzzy roll, no longer interested in random beards and shirts.

Other books

Back Home Again by Melody Carlson

Negotiation: A Mafia Love Story (Triple Threat Book 1) by Kit Tunstall, R. E. Saxton

I'll Mature When I'm Dead by Dave Barry

Arielle Immortal Awakening by Lilian Roberts

Unlocking the Spell by Baker, E. D.

The Magnificent Showboats by Jack Vance

Brotherly Love in College: Book 2 by Kelsey Charisma

Watched by Warlocks by Hannah Heat

(Blue Notes 2)The Melody Thief by Shira Anthony

Razor's Edge by Sylvia Day