Maggie Cassidy (5 page)

The class filed into school at 7:50

A.M.

, generally things rammed and slammed for the last time in strange antenna'd moments when nobody was saying a word and the edge of the bench was cutting my elbow as I leaned my head on it trying to catch some sleepâin the afternoon I really slept, with great success in homeroom study after one o'clock when not spitballs but love notes were thrown aroundâlate in the school dayâSun morning was orange fire in the un-washed windows, making way for day blue gold as birds whistled in trees, an old man leaned on the canal rail with his pipe in his mouth, and the canal flowedâAll whorly and whirlpools and dense and tragic and to be seen from half a hundred windows of the north side of the high school building, the new one and the old for freshmen. Gigantic, the drownings in that canal would bloat a book, bloat a page, imaginary, dream'd in that clock hour of the rosy jongling lip of kid days in stylish sweaters. Lousy was in his class, all was right with the world. He abhorred and grinned on his end of a bench in the flaming sun atmospheres of the southwest windows, which in the winter received pale tropical flame from old northeastâthe eraser's set out, the personal face-type's got his desk, he hangles and grows frowzy, somebody's got to set him right, the yawning day's just begun. Magazines, peeking at them a minute in his desk box, the lid upâ“Oh there in the hall goes Mr. Nedick the English teacher with the oversized pantsâMrs. Faherty the freshman grade or 9th grade teacher of Shakespearean rhymes'll come among us, there she is, the big important tack-tock of her biglady high heels,” Joycean imaginings fill all our minds as we sit there goofily self-enduring the morning, waiting for the grave to lean our heads in, not knowing. In the cobbles by the factory by the canal I understand future dreams. I'll have them later on of the redbrick mills beyond vacant canals in blue morning, the loss brow-banging, done withâMy birds will twitter on the branch of other things.

Eyes of pretty brunettes, blondes and redheads of the Lowell Prime are all around me. A new day in school, everybody wide-awake looking everywhere; today 17,000 notes will be delivered from shivering hand to hand in this ecstatic mortality. I can already see Stendhalian plots forming in the frowns of pretty girls, “Today, I'll keep that damn Beechly awful innerested in a little idee of mine”âlike Date-with-Judies self-communing monologuesâ“bring my brother into it and then everything'll be set.” Others not plotting, waiting, dreaming the enormous sad dream of high school deaths you die at sixteen.

“Lissen, Jim, tell Bob I didnt

mean

âhe knows it!”

“Sure, I told you I would!”

Running for vice-president of the sophomore class, pinning photos to crucial letters, rounding up a gang, trying to get something on Annie Kloos. They're all talking anxiously their plots, across the aisles, up and down the benches; the hubbub is so fantastic uproar momentous, weird, like sudden roars of Friday Afternoon California High School Football Games over quiet bungalow roofs, like teenagers at a roller derby, the teacher even is amazed and tries to hide behind the New York

Times

bought on Kearney Square at the only place where you can get them. The whole class invincible, the teacher'll get the authority at exactly the time but better not interfere before overtime startsâ“Gonna by gollyâ” “well geeâ” “Heyâ” “What you say there!” “Hi!” “Dotty?âdidnt I tell you that dress would look

divine

?”

“You didnt miss a trick, honey, I was perfect.”

“The girls were wild about it, all of them. You shoulda heard Freda Ann come on! Yerr!”

“Freda Ann?” primping her hair very significantly. “Tell Freda Ann she can go along her own way I can get along without her commentsâ”

“Oh along along. Down in the hall's my brother Jimmy. He's got that little dumb Jones kid with him?” They join and peek, lip to ear. “See Duluoz up there? He's bringing a note from Mag-gie Cassidy.”

“Who?

Mag-gie Cassi-dy?

” And they double and squeal and laugh and everybody turns to look, what are they laughing about, teacher's about to slap for orderâthe girls are laughing. My ears burn. I turn my dreamy inattention on everybody, thinking about my hot date pie with whipped cream last Sundayâthe girls are looking into my blue windows for romance.

“Hmm. Isnt he dreamy?”

“I dont know. He looks sleepy all the time.”

“That's the way I likeâ”

“Oh get awayâhow do you know how you like?”

“Wouldnt you like to know? Askâ”

“Ask

who?

”

“Ask who went with Freda Ann to the Girl Officers' Ball last Thursday and found themselves all tangled up, with Lala Duvalle and her gang of cutthroats and fingernail scratchers and you know who and know what else? I'mâOh, here's the silence.”

Blam, blam, the old teacher bangs her ruler and stands, very matronly, like an old busdriver, surveying the class for absences and then she makes a note and a few quibblings then from next room walks in Mr. Grass for some special news and everybody bends an ear as they whisper up front, a spitball sails funnily in the bright nice sun, and on comes the day. The bell. We all rush off to our first classes. Ah inconceivably lost the corridors of that long school, those long courses, the hours and semesters I missed, I played hooky two times a week on the averageâGuilt. I never got over itâClasses in English . . . reading the very solid poetry of Edwin Arlington Robinson, Robert Frost and Emily Dickinson: a name I never knew to reckon with Shakespeare's. Wonderful classes in some kind of pre-science fiction astronomy, with an old lady with a long stick demonstrating moons at the blackboard. A class in physics, here we were blearily lost trying to spell the word barometer on our gray blue-lined examination paper let alone Galileo. A course in this, that, hundreds of beautiful intelligent young people hung on pursuits of pure mental interest and social jawbones, all they gotta do is get up in the morning, school takes care of the rest of their day, taxpayers support.

Some of them preferred rides to the country in tragic rumble seats, we never saw them again, they were swallowed in reform schools and marriage.

It being winter, I wore my football sweater letter “L”âto show offâit was huge, uncomfortable, too hot, I hung braced in its horrible corset of wool for hours on end day after day. Finally I settled to just my own blue home sweater buttoned down in front.

The second class was the Spanish one where I found the notes from Maggie, two a week. I read it right away:

Well I suppose you thought I would never write a note this week. Well I had a swell time in Boston Saturday with my mother and sister. My little silly sister is a little flirt. I dont know what she will be like when she grows up. Well what have you been up to since I saw you. My brother and June that are getting married in April were here last night. How is school? Roy Walters is at the Commodore Tuesday and I am going. Glenn Miller is coming later on. Did you go to the diner after you left me Sunday? Well I havent any more to say now so

So-Long M

AGGIE

.

Even if I was supposed to see her that night I still had a long way to goâafter school it was track, til 6, 7

P.M.

when it was my custom to walk home one mile with stiff legs. Track was in a low vast building across the street, with steel beams bare in the ceiling, great basketball floors six of them, then drill floor of the High School Regiments and sometimes several indoor football drills and some rainy day March baseball practice and big track meets with crowds sitting in bleachers around. Before going there I hung out at the empty halls, classroomsâsometimes met Pauline Cole under the clock which I'd done every day in December but now it was January. “There you are!” She gave out with a big smile, eyes big, moist, beautifully blue, full big lips over great white teeth, very affectionateâit was all I could doâ“Where you been keepin yourself hey.” Liking her, liking life too, I had to stand there assuming for myself all the gloomy guilts of the soul, out the other end of which my life flowed crying emptying in the dark anywayâweeping for what had been supposedânothing within me to right the wronged, no hope of hope, blear, all sincerity crowded out by world-crowded actual people and events and the slack watery weakness of my own mean resolutionâhungâdeadâlow.

Heirs leap screeching from doctors' laps while the old and the poor die on, and who's to bend over their bed and comfort.

“Oh I have to go to track in a minuteâ”

“Hey can I go see you Saturday night against Worcester?âof course I'm coming anyhow, I'm only asking your permission so you'll talk to me.”

O Wounded Wolfe! (That's what I thought I was, with the reading of a few books later)âAt night I closed my eyes and saw my bones threading the mud of my grave. My eyelashes like an old maid being her most carefully concealed false: “Oh you're coming to a meet?âI bet I'll fall at the start and you wont think I can run.”

“Oh dont worry I read about it in the papers, bigshot.” Poking meâpinching meâ“I'll be watching yerr, heyâ” Then suddenly sadly getting to her girlish point, “I been missin ya.”

“I been missin

you

.”

“How could you!ânot with Maggie Cassidy ya havent!”

“Do you know her?”

“No.”

“Then how can you say that.”

“Oh, I got spies. Not that I care. You know I go with Jimmy McGuire lately. Oh he's nice. Hey you'd like him. He'd make a nice friend for you. He reminds me of you. That nice kid you know, your friend from Pawtucketville . . . Lousy?âa little bit like him too. You all have the same eyes. But Jimmy's Irish, like me.”

I'd stand like a precious being, listening.

“So I get along all right dont you worry I wont knit socks over

you

. . . hey did you hear me sing at the rehearsal for the Paint n Powder show? Know what I sang?”

“What?”

“Remember the night last December we went skating, that pond of yours out by Dracut and comin home in the freezing night with the moon and the frost you kissed me?”

“

Heart and Soul

.”

“That's what I'm goin to singâ” Corridors of time stretched ahead of her, songs, sadnesses, some day she'd sing for Artie Shaw, some day little gangs of colored people would gather around her microphone in Roseland Ballroom and call her the white Billyâthe roommates of her hard-knock singing days would go on to be movie starsâNow at sixteen she sang

Heart and Soul

and had little affairs with bashful sentimental boys of Lowell and pushed them and said “Hey”. . . .

“I'll get you back Mr. Duluoz not that I want you but you'll come crawling, that Maggie Cassidy's only trying to take you away from me to get into the act she wants to have a high school football and track all around athlete if she cant come to high school herself because she was too dumb to graduate from Junior HiâHey Pauline Cole is that nice!” She pushed me, then pulled me to her. “This is the last time I'll meet you under our clock.” It was a big boxlike clock hanging from the wall of the school, donated by some old class when the yellowbricks were newâwe'd had our first trembling meetings under itâWhen she sang

Heart and Soul

in the cold night snow of fields it was the melting of our hearts we thought foreverâThe clock was our big symbol.

“Well I'll see you

some

time.”

“Not under this clock, kid.”

I'd walk home alone, two hours to kill before track practice, up Moody in the wake of all the others long home and already changed for backlot yellings; Iddyboy had led the parade a long time ago with his books and eager eediboy stride (“How there boy?”)âold drunks in the Silver Star and other Moody saloons watching the parade of kidsâNow it was twoâsad walk up through the slums, up the hill, over the bridge into the bright keen cottages and hills of Pawtucketville, perdu, perdu. Far on the Rosemont basin were the afternoon skaters in their blue; over their heads the dreams of clouds long sobbed for and lost.

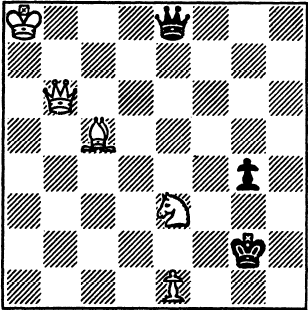

I climbed the stairs to my home on the fourth floor over the Textile Lunchânobody in, gray dismal light filtering through the curtainsâIn gloom I take out my Ritz crackers peanut butter and milk from the pantry with its neat newspaper liningâno housewife of the Plastic Fifties had less dustâThen, kitchen table, the light from the north window, gloom views of grief-stricken birch on hills beyond the white raw roofsâmy chess set and book. The book from the library; Scotch Gambit, Queen's Gambit, scholarly treatises on the combination of openings, the glistening chess pieces palpable to dramatize defeatsâIt was how I'd become interested in old classical-looking library books, tomes, chess critiques some of them falling apart and from the darkest shelf in the Lowell Public Library, found there by me in my overshoes at closing timeâ

I pondered a problem.

The green electric clock in the family since 1933 traveled its poor purring little second-hand around and around the elevated yellow numbers and dotsâthe paint chipping was leaving them half black, half lostâtime herself rolling electrically or otherwise was eating at paints, dust slowly gathering on the hour-hand, in the works inside, in the corners of the Duluoz closetsâThe second-hand kisses the minute-hand sixty times an hour 24 hours a day and still we swallow in hope of life.

Maggie was far away from my thoughts, it was my rest hourâI went to the windows, looked out; looked in the mirror; sad pantomimes, faces; lay in the bed, everything unutterably gloomy, yawning, slow to comeâwhen it would come I wouldnt know the difference. In the bleak, birds squeak. I flexed my current muscles at the mirror's flat unbending blind blareâOn the radio dull booming statics half obliterated lowly songs of the timeâDown on Gardner Street old Monsieur Gagnon spat and walked onâThe vultures were feeding on all our chimneys,

tempus

. I stopped at the phosphorescent crucifix of Jesus and inwardly prayed to sorrow and suffer as He and so be saved. Then I walked downtown again to track, nothing gained.

The high school street was empty. A late winter afternoon pinkbleak light had fallen over it now, it had been reflected in Pauline's sad eyesâSagging old snowbanks, a black tree, weak sister sun on the side of an old buildingâthe keen speechless winter blue beginning to appear over eastern eve roofs as the western ones pulse to the rose of distant dayfire dimming off the low cloudbanks. The last clerk's stacking sales slips in Bon Marche's. Dusk bird bulleted to his darknesses. I hurried to the indoor track, where the runners drummed on boards in a dark inside tragedy of their own. Coach Joe Garrity stood bleakly clocking his new 600-yard hope who in gladiator doom pumped and pulled elastic legs to expectation. Little kids threw final meaningless socks at the farthest baskets as Joe hollered to clear the gym, echoing. I ran into the lockers to jump into my track shorts and tightfitting slipper sneakers. The gun barked the first 30-yard heat, the runners shot from tilted fingertips and dug the planks away to go. I made preliminary warm-up runs around hollow clamoring board banks. Cold, goosepimples on my arms, dust in the dumb gym.

“All right Jack,” said Coach Garrity in his low calm voice, carrying across the planks like a mesmerist's, “let's see you try that new arm motionâI think that's been stoppin you for sure.”

In inconceivable goofiness of my own mad mind I'd been for almost a month imitating the way Jimmy Dibbick ran, he was a distance runner, none too good, but had a way of pulling himself as he ran, hands far out fingertips stretched pointing pull-pumping like that into air reachingâa screwy style that I imitated just for fun; however in the dash, in which I was Number One man on the team beating at that time even Johnny Kazarakis who in another year beat everybody in the Eastern high schools of the United States but wasnt developed yetâthe reach style was bad for my dash, I usually made 3.8 seconds in the 30, now I was retarded to 4 flat and getting beat by all kinds of kids like Louis Morin who was fifteen years old and wasnt even on the team yet just wore tennis sneakers of his ownâ“Run like you used to do,” said Joe, “forget your arms, just run, think of your feet,

run, go

,âwhatsamatter you got woman troubles?” he grinned cheerlessly but with a wise humor gained from the fact that he lived no life of recognition and ease, the best track coach in Massachusetts he nevertheless worked at some desk job all day in City Hall and had a handful of responsibility small-paying him. “Come on Jack, runâyou're my only sprinter this year.”

In the low hurdles among these kids I couldn't beat, I flew ahead; in Boston Garden roaring with all the high schools of New England I ran meek thirds behind longlegged ghosts two of them from Newton and everybody from Brockton, from Peabody, Framingham, Quincy and Weymouth, from Somerville, Waltham, Maiden, Lynn, Chelseaâfrom the bird, endless.

I got down on the line with a group of others, spat on the planks, dug my sneakers in, balanced, trembling, shot off expecting Joe's gun and had to walk back sheepishâNow he held the gun up, we teetered, wondered, aimed eyes down the boardsâBRAM! Off we go, I kick myself out with my right arm I let the arms pump themselves crosswise over my chest and run headlong falling for the line furious. They clock me in 3.7, I win by two yards blamming into the big mat against the finish line wall, glad.

“There,” says Joe, “didja ever hit 3.7 before?”

“No!”

“They musta made a mistake timing. But you got it now, pump those arms natural. All right! Hurdles!”

We put up the low hurdles, wood, some of them need new nails. We line up, blam, off we goâI've got every step figured, by the time we reach the first hurdle my left leg is ready to go over, I do so, slapping it down fast on the other side,

stepping

, the right leg horizontal folded to fly, arms swinging the move. Between first and second hurdles I jump and sprint and stretch and bound the necessary five strides and go over again, this time alone, the others are behindâI go down to the tape 35 yards two hurdles in 4.7.

The 300 was my nemesis; it meant running as fast as I could for almost a minuteâ39 seconds or soâa terrible grueling grind of legs, bone, muscle, wind and flailing poor legs lungsâit also meant gnashing smashing bumps with the others around the first turn, sometimes a guy'd go flying off the bank flat on his ass on the floor full of slivers it was so rough, foaming-at-the-mouth Emil Ladeau used to give me huge whomps on the first bank and especially the last when panting sickfaced we stretched that last twenty yards to die at the tapeâI'd beat Emil but I told Joe I didnt want to run that thing any moreâhe conceded to my sensitivity but insisted I run in the 300-yard relays (with Melis, Mickey McNeal, Kazarakis)âwe had the best 300-yard relay in the state and even beat St. John's Prep older collegians in the Boston finalsâSo every afternoon I'd have to run the bloody 300 usually in a relay race, just to the clock, against another little kid twenty yards behind me and no footballing on the banksâSometimes girls would come and watch their boyfriends in track practice, Maggie'd never have dreamed it she was so gloomy and lost in herself.

Pretty soon it'll be time for the 600âthe 1000âbroad jumpâshot putâthen home we goâfor supperâthen the phoneâand Maggie's voice. Aftersupper Lowell talking to meâ“Can I come tonight?”