Malaria and Rome: A History of Malaria in Ancient Italy (46 page)

Read Malaria and Rome: A History of Malaria in Ancient Italy Online

Authors: Robert Sallares

Tags: #ISBN-13: 9780199248506, #Oxford University Press, #USA, #History

⁷⁸ Aelian,

On animals

11.16; Propertius,

Elegies

4.8.3–14, ed. Fedeli (1984). There is no sign of an association with disease in these texts. The dragon cult is presented as an agricultural fertility rite by Propertius.

⁷⁹ Tomassetti (1910: ii. 497). A modern painting in the church of St. George in Maccarese portrays the saint slaying a dragon. Levi (1945: 96–7) and Douglas (1955: 102–7) discussed dragons in Lucania and Calabria, while Horden (1992) considered the dragon motif in relation to malaria in the lives of the saints in early medieval France.

⁸⁰ Santi (1996: 126).

⁸¹ Tomassetti (1910: ii. 390–1).

The countryside immediately surrounding the city of Rome, the Campagna Romana, requires attention now. In view of the warm climate for most of the period of the Roman Empire (see Ch. 4. 5

above), malaria was probably even more widespread then than it was in the early modern period, when Giordano described the region as follows:

The Tiber and its tributaries, which flow across it sunk into deep channels, have cut into the uneven surface of this plain, which is almost everywhere uncultivated, with only natural pastures, bare of trees and property, the home of malaria in summer.¹

Tomassetti, an expert on the Roman Campagna, wrote about its fauna as follows:

The very common fly (

Musca domestica

) and the mosquito (

Culex pipiens

) . . .

the one by day, the other by night, are the greatest nuisance to visitors to the Roman Campagna in summer.²

Even in the vicinity of Rome as recently as the nineteenth century, it could be difficult to obtain precise and trustworthy information about the distribution of malaria. Tommasi-Crudeli, for example, observed that there were many reasons for people to tell lies about malaria:

Sometimes they imagine that you are a collector of taxes, and tell you that a place is pestiferous, although it is not, in order that you may not be induced to raise their assessment. At other times they take you for a would-be purchaser, and assert that the place is healthy, even when it is extremely malarious, in order to induce you to buy. Cases are known in ¹ F. Giordano, chapter entitled

Condizioni topografiche e fisiche di Roma e Campagna Romana

in Monografia

(1881: p. ii):

Questa planizie di superficie ineguale, incisa dal Tevere e dai suoi influenti che vi scorrono incassati entro profondi solchi, presentasi quasi ovunque incolta ed a soli pascoli naturali, nuda d’al-beri e di cose, sede di mal’aria in estate

.

² Tomassetti (1910: i. 16):

La volgarissima mosca (Musca domestica) e la zanzara (Culex pipiens) . . .

l’una di giorno, l’altra di notte, formano la più grande molestia di chi frequenta in estate la campagna romana

.

Blewitt (1843: 534) mentioned the abundance of mosquitoes along the direct road from Rome to Anzio (ancient Antium).

236

Roman Campagna

which they will tell you a falsehood, rather than speak the truth, for fear of ruining their trade.³

In the same decade in which he wrote the original Italian version of his book, the Italian government in fact made a great effort to gather information about the distribution and frequency of malaria in every district of Italy for the monumental

Carta della malaria dell’

Italia

, inspired by Luigi Torelli. This map, completed in 1882, was apparently so large and detailed that it would cover a town square if all the sheets were laid out on the ground side by side. After considering all the difficulties, Tommasi-Crudeli went on to reach the following conclusion:

We must admit that malaria prevails throughout the whole extent of the Campagna, although there are abundant reasons for believing that some localities are much more malarious than others, and that some are entirely free from it.

Obviously it is far more difficult to obtain information now regarding the situation two thousand years ago than it was to assess the then current situation little more than a hundred years ago.

However, bearing in mind the evidence of ancient medical writers that malaria was frequent within the city of Rome itself and the statements of Cicero and Livy, implying that Rome was situated in an unhealthy region, the balance of probability is that many of the low lying rural districts of Latium and southern Etruria were also affected by malaria during the time of the Roman Empire just as they were in more recent times. It is worth describing some features of the ecology of Latium in Roman times to show how it fits this suggestion. Pliny the Younger described the countryside along the roads from Rome to Laurentum in the first century . These roads passed through woods, which provided plenty of firewood (though Pliny does not mention timber good enough for construction purposes in Rome), and extensive meadows where there were numerous flocks of sheep and herds of cattle and horses which were driven down from the mountains in winter to pasture on the well-watered meadows overlying the very high water table. Indeed these pastures were so rich that elephants were kept in the region between Laurentum and Ardea in readiness for the circuses in Rome.⁴

³ Tommasi-Crudeli (1892: 86), cf. Levi (1945: 32, 74) on taxes and lies.

⁴ Pliny,

Ep

.2.17.3; the inscription

CIL

VI.8583,

procuratoris Laurento ad elephantos

(procurator [

cont. on p. 238

]

Roman Campagna

237

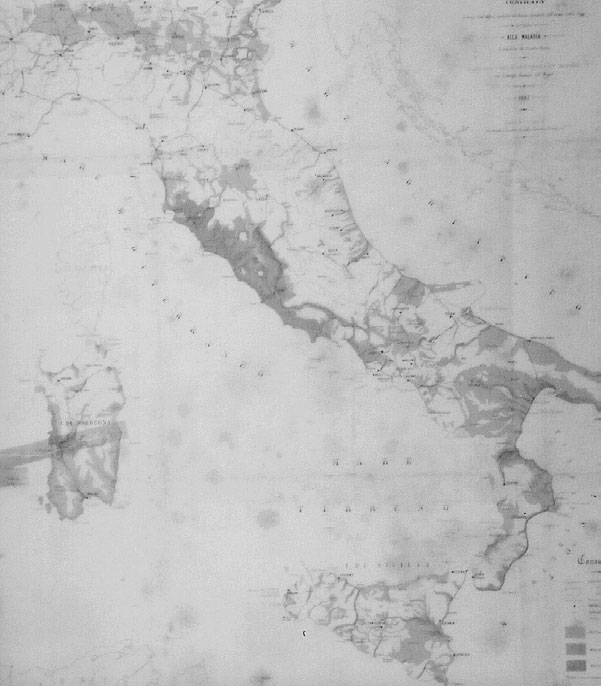

35. Luigi Torelli’s

Carta della malaria dell’Italia

, completed in 1882. Geographical areas with

P. falciparum

malaria have dark shading, areas with only

P. vivax

malaria have light shading.

238

Roman Campagna

These meadows were natural meadows, not artificial ones, just as in Lazio in the nineteenth century, since the Roman agronomists in antiquity did not have any conception of the complicated crop rotation systems required for artificial meadows. In any case the forage crops of artificial meadow systems, such as lucerne, grew naturally in such a well-watered (in winter) environment. According to the early modern Roman agronomists stall feeding of stabled animals was disliked in Lazio because it was felt that animals tended to become infected with diseases if they were not allowed to roam freely. In 1813 33% of the total value of all agricultural production in Lazio came from animal husbandry. This demonstrates in quantitative terms the importance of animal husbandry to the agricultural economy, and explains why the élite in Rome throughout history took such an interest in it.⁵ In the sixth century

Procopius noted that the invading Gothic army chose to set up a camp at Regata near Terracina because the Goths observed that the lush Pontine plain was very suitable for feeding the horses of their cavalry.⁶

However, the agricultural system of Latium in antiquity was one in which animal husbandry was not integrated with arable farming. Pliny took transhumance for granted as the basic pattern of animal husbandry. This traditional system continued from antiquity up to and throughout the nineteenth century. It can be inferred that shepherds in antiquity were as vulnerable to infection with malaria when they came down from the mountains in late autumn as Marchiafava noted they were in the nineteenth century. The poem

Culex

in the

Appendix Vergiliana

tells a fable about a shepherd sleeping out in the countryside who was about to be attacked by a poisonous snake when he was woken up and saved by a mosquito biting him. The ungrateful shepherd killed the mosquito, which descended to the underworld and then reappeared to him in a for elephants at Laurentum) and Juvenal,

Sat.

12.102–5 record the presence of elephants in this region.

⁵ Sallares (1991: 382–4) on meadows in antiquity; De Felice (1965: 38–40, 89–104) on meadows and animal husbandry in early modern Lazio; Gabba & Pasquinucci (1979) and Garnsey (1988

b

) on antiquity.

⁶ Procopius,

BG

1.11.1 (cf. 2.3.10–11 for the vicinity of Rome itself ). Nicolai (1800: 42–3) discussed eighteenth-century opinions on the location of Regata or Regeta. He noted Cluverius’ textual emendation of the name to Pineta and Olstenius’ emendation to Trajecta, but followed Corradini’s view that Regata was situated between Forum Appii and ad Medias along the Via Appia.

Roman Campagna

239

dream.⁷ This tale evidently lacks realism in more ways than one. It shows no awareness at all of the danger of mosquito bites and the link between mosquitoes and malaria. Nevertheless it is quite realistic in suggesting that being bitten by mosquitoes was an occupa-tional hazard for shepherds in the Roman Campagna.

However, the question of animal husbandry and agricultural systems has a wider significance in relation to malaria. It was noted earlier that species of mosquito may be anthropophilic, or zoophilic, or indifferent with regard to their choice of prey. In the Campagna Romana in the 1930s the important malaria vector species

A. labranchiae

certainly occurred inland but was most abundant along the coast, from Palidoro to Ardea. Its larvae seemed to require a certain degree of salinity in the water. Fluctuations in the size of populations of

A. labranchiae

were correlated with fluctuations in the frequency of malaria. Away from the coast in the 1930s the zoophilic

A. typicus

was commoner, while another zoophilic species,

A. messeae

, was very rare. Zoophilic female mosquitoes prefer cattle, but may also dine on pigs or horses instead. They are not so keen on sheep, whose woolly fleece provides protection from mosquito bites. Consequently a system of arable farming, using cattle to pull the plough, may sometimes deviate some species of mosquitoes away from humans towards cattle, especially if fodder crops alternate with cereals, increasing the number of animals that can be kept on the arable farm in summer, the crucial time of the year.⁸ This raises many important questions about the nature of ancient agriculture in Mediterranean-climate regions, such as the question of the prevalence or otherwise of fallow in arable farming, or that of the scale of cultivation of fodder crops, or of the extent to which animals were actually maintained permanently on farms.

These issues cannot be explored in detail here, beyond expressing general agreement with the analysis of Roman agriculture made by Ampolo and his use of comparative material from the early modern period.⁹

In contrast, a dominance of transhumant animal husbandry, especially if it concentrates on sheep, may have the effect of driving mosquitoes towards humans. In addition, a critical feature of transhumance is that the animals are absent from the parched lowlands ⁷ Marchiafava (1931: 52);

Culex

182–9.

⁸ Hackett (1937: 89); Missiroli

et al

. (1933); Sandicchi (1942).

⁹ Ampolo (1980).

240

Roman Campagna

during the summer heat, which is precisely the time of year when adult female mosquitoes are searching for prey to bite.¹⁰ In the early modern period transhumance commenced in the Pontine region in May each year, earlier than in the Roman Campagna, because of the greater intensity of malaria in the Pontine Marshes.

The system of land use along the road from Rome to Laurentum, described by Pliny the Younger, probably increased the intensity of transmission of malaria to humans in the countryside of Latium in antiquity in summer by deviating mosquitoes from animals to humans. Similarly, Bercé thought that an increasing interest in animal husbandry on the part of rich absentee landowners, to supply the urban market in Rome with meat and wool, which commanded higher prices than cereals, was correlated with an intensification of malaria in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries .

Celli had already noted the debates in the Gracchan period in the second century , concerning the appropriation of public land (

ager publicus

) by rich Romans and its exploitation for animal husbandry, which cannot be considered in detail here. Suffice it to say that this development was correlated with the spread of malaria in central and southern Italy, although it is difficult to specify cause and effect. The history and consequences for the Roman Republic of the Gracchan attempts at agrarian reforms are well known. It is only worth observing here that the question of appropriation of land by the rich for pastoralism was a perennial problem throughout the agrarian history of western central Italy. It was as prominent an issue in Lazio in the eighteenth century as it was in Latium in the time of the Gracchi in the second century . The comparison with detailed accounts of the very same phenomenon in much more recent and better-documented times shows that ¹⁰ The only large domesticated animal (leaving aside the elephants) whose entire population spent the whole year in the lowlands of Latium in the pre-modern period was the water-buffalo (the source of mozzarella cheese), first mentioned in Italy by Paulus Diaconus,

historia Langobardorum

, iv.10, ed. G. Waitz (1878),

Monumenta Germaniae Historica

, xlviii (

Scriptores

7) in the late sixth century :

tunc primum cavalli silvatici et bubali in Italiam delati, Italiae populis miracula fuerunt

(At that time wild horses and water-buffaloes were brought to Italy for the first time, marvels for the peoples of Italy). However it should be noted that there is some uncertainty about the identification of the

bubali

in the text of Paulus Diaconus: the aurochs is another possibility (White 1974). Toubert (1973: i. 268–9) suggested that water-buffaloes (

bubali

) might have served to deviate mosquitoes away from humans. This was certainly a possibility, but since malaria remained endemic in Lazio until Mussolini’s bonifications, there were probably never enough buffaloes around to make a real difference. Hare (1884: ii. 271) described water-buffaloes in the Pontine Marshes. These animals have their own specific species of malaria,

Plasmodium bubalis

(Garnham (1966: 494–9) ).