Mark Griffin (41 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

Fidgety and easily agitated even on the back lot in Culver City, Minnelli was all jangled nerves on location. While he was pushing himself, the cast, and the crew to the limit in the oppressive heat, a series of calamities befell the overburdened director. Vincente’s omnipresent boom smashed through the tinted glass ceiling at Maxim’s, and somewhere between shooting the skating sequence at the Palais de Glace and Eva Gabor’s illicit rendezvous in Montfort-l’Amaury, Minnelli contracted whooping cough. Then, while shooting the title number in the Jardin de Bagatelle, the director was bitten by one of the swans he had painstakingly “auditioned” for four days.

Back in Hollywood, Metro executives were equally frazzled. Although Elvis Presley was setting the box office on fire with

Jailhouse Rock

, many of the studio’s other recent releases had tanked. For the first time in the studio’s history, MGM lost money, sinking some $455,000 into the red. At the end of August, Ben Thau summoned Minnelli and company back to Culver City. In an effort to curtail expenditures and keep a closer eye on Vincente’s extravagant endeavor, angsty executives insisted that the rest of the picture would have to be completed on the lot.

Jailhouse Rock

, many of the studio’s other recent releases had tanked. For the first time in the studio’s history, MGM lost money, sinking some $455,000 into the red. At the end of August, Ben Thau summoned Minnelli and company back to Culver City. In an effort to curtail expenditures and keep a closer eye on Vincente’s extravagant endeavor, angsty executives insisted that the rest of the picture would have to be completed on the lot.

The only thing remaining in Paris was Georgette Magnani. She had decided that her marriage to Vincente was over. At this point, it had to have been perfectly clear to her that she would always be competing with something for her husband’s attention: his latest picture, the studio, Judy’s enormous shadow, Liza, a thick volume on Leonardo da Vinci, or any number of Vincente’s other romantic interests. Even on the rare occasions when the couple were actually in the same room, Minnelli could still be pretty hard to find. “Vincente was in another world. He was a dreamer,” Magnani would later remark.

11

11

Shooting resumed in California in September. Venice Beach, which usually played host to body builders and bohemians, stood in for France’s Trouville. For the scenes depicting Gigi and Gaston’s carefree weekend by the sea, Minnelli hoped to emulate the style of French landscape painter Eugene Boudin—or at least what he thought was Boudin. Taking his cue from Vincente, Cecil Beaton outfitted the actors and extras in dark shades like the ones on display in Boudin’s 1869 painting

Bathers on the Beach at Trouville

. When Minnelli saw the results, he was aghast. The director had envisioned his seascape in bright pastels. Of course, that kind of palette was more in league with the Impressionists (Renoir, Manet), but Beaton didn’t bother to

argue. Instead, he doled out colorful clothing and accoutrements in an attempt to give Vincente the Impressionist effect he wanted.

Bathers on the Beach at Trouville

. When Minnelli saw the results, he was aghast. The director had envisioned his seascape in bright pastels. Of course, that kind of palette was more in league with the Impressionists (Renoir, Manet), but Beaton didn’t bother to

argue. Instead, he doled out colorful clothing and accoutrements in an attempt to give Vincente the Impressionist effect he wanted.

Beaton, for one, believed that artifice was winning out over authenticity. “All the scenes that were taken in Hollywood were very damaging,” the designer remarked. “To me, the whole success of the film was the Parisian flavor and that was created by making it in France. As soon as we had a swan on the back lot, it looked like the back lot.”

12

12

Chuck Walters, who had made contributions to Minnelli’s

Ziegfeld Follies

and had helmed Leslie Caron’s 1953 sleeper

Lili

(which Vincente had declined to direct), was called in to choreograph the exuberant “The Night They Invented Champagne,” one of the few musical numbers in

Gigi

that features dancing. Minnelli had graced the picture with a stately elegance, but it was Walters who added a welcome ingredient: energy. Throughout the film, the principals often perform their songs while seated. In a refreshing change of pace, Walters gets everyone up on their feet and moving.

Ziegfeld Follies

and had helmed Leslie Caron’s 1953 sleeper

Lili

(which Vincente had declined to direct), was called in to choreograph the exuberant “The Night They Invented Champagne,” one of the few musical numbers in

Gigi

that features dancing. Minnelli had graced the picture with a stately elegance, but it was Walters who added a welcome ingredient: energy. Throughout the film, the principals often perform their songs while seated. In a refreshing change of pace, Walters gets everyone up on their feet and moving.

In the three months between the official end of production and the initial preview,

Gigi

was the cause of much in-house intrigue. Minnelli had been so entranced with the atmosphere at Maxim’s that he had favored long shots while shooting there. But what about close-ups of Louis Jourdan during “She Is Not Thinking of Me”? These were needed to reinforce the notion that the viewer was eavesdropping on Gaston’s private thoughts. At great expense, close-ups of Jourdan would have to be shot in Hollywood with a carefully reconstructed set doubling as Maxim’s. Another mad scramble ensued. After assisting with this and countless other emergencies, Freed’s overwhelmed assistant Lela Simone finally threw in the towel after years of dedicated service.

Gigi

was the cause of much in-house intrigue. Minnelli had been so entranced with the atmosphere at Maxim’s that he had favored long shots while shooting there. But what about close-ups of Louis Jourdan during “She Is Not Thinking of Me”? These were needed to reinforce the notion that the viewer was eavesdropping on Gaston’s private thoughts. At great expense, close-ups of Jourdan would have to be shot in Hollywood with a carefully reconstructed set doubling as Maxim’s. Another mad scramble ensued. After assisting with this and countless other emergencies, Freed’s overwhelmed assistant Lela Simone finally threw in the towel after years of dedicated service.

The rest of the team soldiered on, including editor Adrienne Fazan, who was tasked with putting all the pieces of

Gigi

together. At one point, Margaret Booth, the venerable grande dame of the MGM editing department, was brought on to assist with cutting the picture. But in Fazan’s eyes, Booth butchered the film, hacking out the very heart of the story: “She cut all the warmth out of it—with Chevalier, Caron, Gingold, everybody!”

13

Gigi

together. At one point, Margaret Booth, the venerable grande dame of the MGM editing department, was brought on to assist with cutting the picture. But in Fazan’s eyes, Booth butchered the film, hacking out the very heart of the story: “She cut all the warmth out of it—with Chevalier, Caron, Gingold, everybody!”

13

It was this version of

Gigi

that was first previewed on January 20, 1958, at the Granada Theatre in Santa Barbara. The reception the film received reminded its creators of Howard Dietz’s comment to Arthur Freed upon hearing Lerner and Loewe’s score for the first time: “Arthur, this will be the most charming flop you ever made.”

14

MGM’s upper echelon was reasonably satisfied with the audience’s reaction to the picture, but the composer and lyricist did not share their optimism. For Lerner and Loewe (and especially

Lerner), there was something missing. Although the film was visually spectacular, the warmth and intimacy of Colette’s story only occasionally found its way to the screen. Pacing was another problem—some scenes overstayed their welcome, while others (such as Caron’s “The Parisians”) seemed to flit by without making any impression. The orchestrations, according to Lerner, were “too creamy and ill-defined.” The team that had galvanized Broadway with

My Fair Lady

left the preview feeling that their

Gigi

had somehow slipped away. “To Fritz and me, it was a very far cry from all we had hoped for, far enough for both of us to be desperate,” Lerner said. “The ride home from Santa Barbara was not unlike the ride home from any funeral.”

15

Gigi

that was first previewed on January 20, 1958, at the Granada Theatre in Santa Barbara. The reception the film received reminded its creators of Howard Dietz’s comment to Arthur Freed upon hearing Lerner and Loewe’s score for the first time: “Arthur, this will be the most charming flop you ever made.”

14

MGM’s upper echelon was reasonably satisfied with the audience’s reaction to the picture, but the composer and lyricist did not share their optimism. For Lerner and Loewe (and especially

Lerner), there was something missing. Although the film was visually spectacular, the warmth and intimacy of Colette’s story only occasionally found its way to the screen. Pacing was another problem—some scenes overstayed their welcome, while others (such as Caron’s “The Parisians”) seemed to flit by without making any impression. The orchestrations, according to Lerner, were “too creamy and ill-defined.” The team that had galvanized Broadway with

My Fair Lady

left the preview feeling that their

Gigi

had somehow slipped away. “To Fritz and me, it was a very far cry from all we had hoped for, far enough for both of us to be desperate,” Lerner said. “The ride home from Santa Barbara was not unlike the ride home from any funeral.”

15

Gigi (Leslie Caron) and Gaston Lachaille (Louis Jourdan) come to terms.

Gigi

must have been one of the films that director Billy Wilder had in mind when he said, “I don’t shoot elegant pictures. Mr. Vincente Minnelli,

he

shot elegant pictures.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Gigi

must have been one of the films that director Billy Wilder had in mind when he said, “I don’t shoot elegant pictures. Mr. Vincente Minnelli,

he

shot elegant pictures.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

After some tightening and fine-tuning, there was a second preview, which to Lerner and Loewe seemed as uninspiring as the first. Clearly, something would have to be done. “We were determined that the picture not be released the way it was,” Lerner recalled.

16

However, recalling the actors, reshooting entire sequences, and arranging for additional scoring would come with a hefty price tag. It seemed highly unlikely that the studio would open its checkbook for a production that had already gone over budget. Besides, Minnelli was already back in Paris preparing his next film,

The Reluctant Debutante

. Nevertheless, Lerner and Loewe insisted on changes.

16

However, recalling the actors, reshooting entire sequences, and arranging for additional scoring would come with a hefty price tag. It seemed highly unlikely that the studio would open its checkbook for a production that had already gone over budget. Besides, Minnelli was already back in Paris preparing his next film,

The Reluctant Debutante

. Nevertheless, Lerner and Loewe insisted on changes.

“They wanted a lot of work to be done on the picture,” says Lerner’s former assistant Stone Widney. “As Alan tells it, it was going to cost three hundred grand to do the retakes. Vincente had already gone on to another movie and wasn’t available. But Alan and Fritz stuck to their guns and offered to buy the print back from the company themselves and finish it. . . . I think the scoring was totally incorrect as far as Fritz was concerned, even though André Previn had done it. Fritz felt that it was way overboard.”

17

17

In a desperate ploy, Lerner and Loewe offered to buy “10 percent of

Gigi

for $300,000.” Later, they upped their offer to $3 million for the purchase of the film’s negative (even though they didn’t have that kind of money). The elaborate ruse worked. Metro executives Joseph Vogel and Ben Thau were so impressed with Lerner and Loewe’s commitment that they agreed to lavish an additional $300,000 on the picture—anything to make

Gigi

perfect. Although Minnelli would not be involved in the retakes on

Gigi

, Lerner felt an obligation to play messenger and relayed the news to the absentee director, who noted: “When you’re in another country and you hear that the picture you made didn’t go over well and that parts of it are being reshot, you tend to believe that the picture couldn’t have been any good,” Minnelli said.

18

Gigi

for $300,000.” Later, they upped their offer to $3 million for the purchase of the film’s negative (even though they didn’t have that kind of money). The elaborate ruse worked. Metro executives Joseph Vogel and Ben Thau were so impressed with Lerner and Loewe’s commitment that they agreed to lavish an additional $300,000 on the picture—anything to make

Gigi

perfect. Although Minnelli would not be involved in the retakes on

Gigi

, Lerner felt an obligation to play messenger and relayed the news to the absentee director, who noted: “When you’re in another country and you hear that the picture you made didn’t go over well and that parts of it are being reshot, you tend to believe that the picture couldn’t have been any good,” Minnelli said.

18

Chuck Walters was called back to oversee nine days of reshoots. “Gaston’s Soliloquy” was reattempted; Caron marched through “The Parisians” yet again; Hermione Gingold uttered her final line, “Thank heaven . . .” with the quiet contentment that Lerner was looking for. Now it was up to editor Adrienne Fazan to sort through the miles of footage and make some attempt at patching together the best of Minnelli and Walters, just as she had pieced together Paris and Culver City. Fazan found herself in a race against time as she attempted to incorporate innumerable changes (most of them Lerner-dictated) into the final edit.

At last, on May 15, 1958,

Gigi

was ready to make her grand entrance, and Freed made sure it was a luxurious red-carpet affair. Radio City Music Hall simply wouldn’t do for a cinematic event this prestigious. Instead, Broadway’s Royale Theatre would have the honor of presenting

Gigi

as though it were a legitimate theatrical attraction—white tie and hard ticket included. In Hollywood, splashy premieres were par for the course, but this was something unique. And the critics knew it. “

Gigi

, the delectable musical film that opened last night at the Royale, is a triumph of style over matter,” declared the

New York World-Telegram

’s William Peper: “Director Vincente Minnelli has taken his CinemaScope and color cameras on a ravishing whirl through Paris. And with the help of a refreshingly witty screenplay by Mr. Lerner, he has given the film a pace and sparkle that belie its tiny plot.” The

New York Times

saluted

Gigi

as the “Fair Lady of Filmdom,” with critic Bosley Crowther

noting, “Vincente Minnelli has marshaled a cast to give a set of performances that, for quality and harmony, are superb.”

Gigi

was ready to make her grand entrance, and Freed made sure it was a luxurious red-carpet affair. Radio City Music Hall simply wouldn’t do for a cinematic event this prestigious. Instead, Broadway’s Royale Theatre would have the honor of presenting

Gigi

as though it were a legitimate theatrical attraction—white tie and hard ticket included. In Hollywood, splashy premieres were par for the course, but this was something unique. And the critics knew it. “

Gigi

, the delectable musical film that opened last night at the Royale, is a triumph of style over matter,” declared the

New York World-Telegram

’s William Peper: “Director Vincente Minnelli has taken his CinemaScope and color cameras on a ravishing whirl through Paris. And with the help of a refreshingly witty screenplay by Mr. Lerner, he has given the film a pace and sparkle that belie its tiny plot.” The

New York Times

saluted

Gigi

as the “Fair Lady of Filmdom,” with critic Bosley Crowther

noting, “Vincente Minnelli has marshaled a cast to give a set of performances that, for quality and harmony, are superb.”

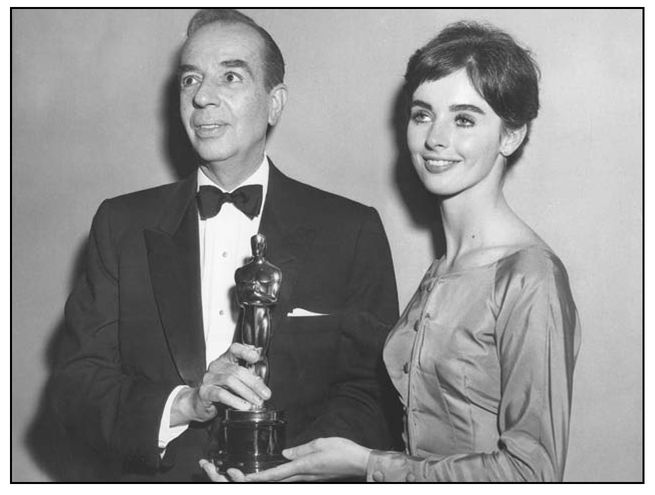

“Thank Heaven for Little Girls”: Oscar night, 1959. Minnelli receives an Academy Award for his direction of

Gigi

. “It’s about the proudest moment of my life,” Vincente declared in his acceptance speech. The presenter is actress Millie Perkins. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Gigi

. “It’s about the proudest moment of my life,” Vincente declared in his acceptance speech. The presenter is actress Millie Perkins. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Variety

would describe Leslie Caron as “completely captivating and convincing in the title role.” Although the actress was ably assisted from all corners, it is her endearing performance that is the centerpiece of the film: her mischievous expression as she reveals that the one thing she wants most is a “Nile green corset with rococo roses on the garters”; her maturing tone as she says, “It’s silly. . . . It’s absolutely silly” in response to the fuss over one of Gaston’s impulsive outbursts; her look of quiet command as she throws open the doors of her bedroom and emerges as a Beatonized bird of paradise.

would describe Leslie Caron as “completely captivating and convincing in the title role.” Although the actress was ably assisted from all corners, it is her endearing performance that is the centerpiece of the film: her mischievous expression as she reveals that the one thing she wants most is a “Nile green corset with rococo roses on the garters”; her maturing tone as she says, “It’s silly. . . . It’s absolutely silly” in response to the fuss over one of Gaston’s impulsive outbursts; her look of quiet command as she throws open the doors of her bedroom and emerges as a Beatonized bird of paradise.

But if the film really belongs to anyone it is Minnelli. “I don’t think of it as an MGM movie,” says writer Ethan Mordden. “It seems to be in its own style entirely.” The sumptuousness serves the story in a unique way. Scenes are so masterfully composed, they are like oil paintings come to life. All of this and an endearing message about trying one’s wings and flying against the flock.

Other books

Sandokán by Emilio Salgari

Hunt the Jackal by Don Mann, Ralph Pezzullo

Fox River by Emilie Richards

A Star is Born by Robbie Michaels

Solo by Alyssa Brugman

Love Scars - 2: Deeper by Lane, Lark

The Weird Sisters by Eleanor Brown

Fool's Gold by Warren Murphy

Magick Rising by Parker Blue, P. J. Bishop, Evelyn Vaughn, Jodi Anderson, Laura Hayden, Karen Fox

Nobody's Goddess by Amy McNulty