Men of Honour (25 page)

There, in a rare moment of excess, some kind of truth is uttered. For those in the horror of battle, it is not horror but delight, a form of the sublime, a moment in which the collapse and disintegration around them, the excess of energy, finds sudden and explosive release in âa very fury of delight.'

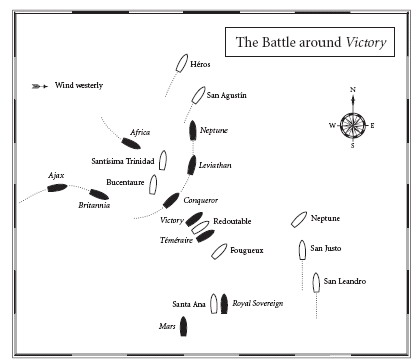

Nelson wanted a conflict that was indescribable, not in the sense of moral revulsion, but as a plain narrative fact. The pell-mell battle, the anarchy in which the individual fighting energies of individual ships and men were released, could not submit to narrative convention. The fleets become their ships, the ships their men, the men their instincts. Decision-making moves from admirals to captains, to gun captains, to the powder-monkeys, the surgeons and their assistants buried in the bloody dark of their cockpits. Lifeâand deathâin Nelsonian battle is atomised, broken into its constituent parts, made to rely not on the large scale manoeuvring of destructive force, but the will to kill and to live. Already, in the first moment of engagement, as

Royal Sovereign

entered the killing zone, that atomisation had begun. Every ship in all fleets considered that they fought Trafalgar almost entirely on their own. The literal fog of battle threw them in on themselves, a half-blind and in most places nearly fearless frenzy from which the British emerged victors and the French and Spanish destroyed. It was the chaos which Nelson required and which his daring approach had imposed on the enemy.

Trafalgar, nevertheless, can be seen to have three distinct phases: the first battle between Collingwood's division and the rear of the Combined Fleet; the long-drawn-out mutual battering between Nelson's division and the centre of the Combined Fleet; and finally, the battle between the van of

the Combined Fleet, which had sailed away from the battle to start with, and a series of individual British ships which, very late in the battle, it had turned to attack. The two conflicting principles of war and of human organisation are apparent in all three phases: fragmentary British aggression, as if the British fleet were an explosive charge, breaking and scattering into tens of equally explosive pieces, coming up against the defensive wall of the Combined Fleet. That wall was inadequate because it was broken from the start, and the detonating elements of British aggressionâthe individual shipsâfound their way between the blocks of which it was made, so that their violence did not break like a wave against a seawall, but entered the body of the enemy's defences and destroyed them from within.

The leading ships, of all three navies, knew that this was to be a tight, close-range affair. Spanish and French ships had prepared for the battle with grappling irons and extensive training in boarding the enemy which those irons held alongside. Grenades were prepared to be thrown down the enemy hatches from the tops of all three masts. The British had loaded their guns with two or even three shots each: ineffective at long range but delivering multiple killing and splinter-creating blows at short range. Every British ship, and several of the Combined Fleet, were armed with short range, large calibre, deck-mounted guns known as carronades, which were mounted not on a conventional gun carriage but on a pivot and swivel which would allow them to sweep the decks of enemy ships alongside. British crews were also provided with lengths of line, which once they had got deep among the mass of the enemy, they could use to lash the French and Spanish ships to their own, holding them there, not hundreds of yards away, not even a few feet away, but bound to each other, their hulls touching at water level, their yards and bowsprits tangled up high above, so that the enemy could not withdraw from the

murderous onslaught of the broadsides which one after another were fired through them and into them. Close to, guns were loaded with reduced powder, to slow down the shot and ensure it remained within the hull of the enemy alongside and didn't burst through to damage a friendly ship beyond it. Guns on high decks were aimed below the horizontal so that the shot would smash their way downwards through deck after deck. The big guns on the lowest tier were aimed upwards, so that in the enemy ship their shot would erupt through the decks beneath men's feet, destroying men's bodies from below. It is as if a boxer, with one hand, was holding the head of his opponent which, with his other, he then bludgeons into submission.

The intimacy of this battle meant that in some ships the muzzles of the French and English guns touched each other. An average British ship, like the

Polyphemus

, eighth behind the

Royal Sovereign

, expended 1,000 24lb shots and 900 18lb shots in the course of the battle, a weight equivalent to 18 tons of cast iron fired at a muzzle velocity capable of killing men and destroying masts at the range of a mile, but here fired into the faces of people six or eight feet away. In many ships, more than 7,000 lbs of gunpowder was used during the engagement. What is extraordinary is not that people died or that ship structures were savaged but that anyone or anything survived.

That story repeats itself again and again at Trafalgar, beginning at the moment that the

Royal Sovereign

broke into the Combined line. Collingwood had aimed just astern of the

Santa Ana

, who had backed her mizzen top-sail to take the way off her. The British ship fired not a shot, apart from one or two to create a curtain of smoke around her, until her guns bore on the Spanish flagship. Collingwood had ordered his guns double-shotted and as they passed under the windows of the stern galleries, the huge, glazed glories of a ship-of-the-line, set in dazzlingly carved

and gilded woodwork, the most theatrical, most honourable and in retrospect most absurd aspect of a ship-of-the-line, behind which admirals and captains had their cabins, and providing by far the weakest point in the entire structure, the

Royal Sovereign

gunners fired one by one, as their guns came to bear.

Any shot that entered through those galleries would travel the length of the ship on all three of its decks. No bulkheads or transverse timbers would interrupt their flight. They would slaughter without difficulty every creature, human and animal in their path. To achieve this longitudinal devastation of a shipâcalled since the mid-17th century a âraking'âfrom a position in which no enemy broadside could be brought to bear, was the aim and the ideal of all late-18th-century ship tactics and the moment of the

Royal Sovereign

's passing of the

Santa Ana

, achieved through Nelson's daring perpendicular approach, was the apotheosis of the killing craft.

The

Santa Ana

carried a crew of some 800 officers, marines and men; 240 of them were killed or wounded in the first raking broadside from the

Royal Sovereign.

If Collingwood's flagship was travelling at about 2 knots, gliding forward at a rate of about 3 feet a secondâin the very light airs, both studding sails and the mainâand fore-courses were shaken out; they wanted every bit of speed out of her they couldâshe would have taken almost exactly a minute to pass under the stern of the

Santa Ana.

That first minute of Trafalgar devastated the Spaniards, half of them recently swept up from the gutters of Cadiz. One Spaniard after the battle was found still to be in the Harlequin clothes he had been wearing when taken from the theatre where he had been entertaining the people of Cadiz. During this minute on the

Santa Ana

they were killed and wounded at a rate of nearly 4 men a second, a screaming, frenzied, terrifying minute, from which there

would have been no escape, and in which the scenes between decks must have been beyond description.

On the long approach of the

Royal Sovereign

, they had scarcely managed to land a single shot on target. The cold silence of the approaching English guns, and the knowledge that this enemy, with such a ruthless reputation, was planning to pass under their desperately vulnerable sternâthat can hardly have helped Spanish resolve. Now the

Sovereign

's weight of metal plunged through her crew, totally disabling 14 of the

Santa Ana

's guns, the full broadside of 50 guns fired once, half of them able to fire again. This was shock and awe. As Collingwood stood on the quarter-deck of his calmly advancing ship, he called out to his captain: âRotherham, what would Nelson give to be here?' There was delight in battle if battle was like this,

in the supremely effective imposition of overwhelmingly damaging force. Two miles away to the northwest, Nelson watched through his telescope from the quarter-deck of

Victory

: âSee how that noble fellow Collingwood carries his ship into action'. It was a form of battle he admired too.

At the same time, on the starboard side of the

Royal Sovereign

, the French

Fougueux

turned her port broadside on to the invading Englishman. On this side too, the

Sovereign

replied, her huge weight of iron slamming into the smaller

Fougueux.

Pierre Servaux was the master-atarms on board:

She gave us a broadside from fifty-five guns and her carronades, belching out a storm of cannon shot, big and small, and musket-shot. I thought the Fougueux must be shattered, pulverised into tiny pieces. The storm of missiles that was driven against and through the hull on the port side made the ship heel to starboard. The larger part of the sails and the rigging was cut to pieces, while the upper deck was swept clear of most of the seamen who were working there and of the marksmen. On the gundecks below, there was less damage. There, not more than thirty men were put out of action. This preliminary greeting, rough and brutal as it was, did not dishearten our men. A well-maintained fire showed the Englishmen that we too had guns and could use them.

Servaux's cool-headed account of that first blast of the iron wind from a British ship-of-the-line is revealing on several counts. There is, to begin with, the sheer volume of aggressive metal which the big three-decker can deliver. Initial shock, conveyed by hugely powerful ships at the head of the two columns, was central to Nelson's scheme. It established a devastating advantage from which recovery was nearly impossible. But Servaux also makes clear two crucial facts

about this form of attack. First, the effect of raking fire and the effect of a broadside received broadside-on is the difference between a battle and a slaughter. Raking fire, poured through the stern or bow of a ship, encountered no obstacle on its way. It met the vulnerable bodies of men and guns as violently as it had left the muzzles from which it had been fired. But gunfire which had to punch its way through the oak walls of the enemy ship could have no such effect. Its killing power was blunted by the density of the wooden defences. Even a broadside that drove the receiving ship over with the impact, as if caught in a vicious squall, did not disable a ship in the way that the

Santa Ana

was smashed by the raking fire on the

Sovereign

's other broadside. Sailing skill, sheer deftness of manoeuvre and the alacrity with which crews would jump to instructions, either turning the ship into a position where it could rake its enemy, or turn itself away from raking fire, were the factors on which life or death depended.

Further than that, in Servaux's words, the difference could not be clearer between the horror of exposure on the upper decksâthe forecastle, the quarterdeck and the poopâand the relative safety of the oak-bulwarked gundecks below. Those upper decks were where the leading figures of the ship needed to be during the battle. Captains, first lieutenants, and masters were all to be found on the quarterdeck, boatswains, other petty officers and prime seamen on the forecastle, marine officers on the poop. These places were where the killing and wounding was done and so among these ranks, in ship after ship, the proportion of casualties often rose to well over a third or even a half. The more significant the man at Trafalgar, the more vulnerable he was.

These conditions were common to all sides, given the current technology. Why, one might ask, did the commanders not have constructed for themselves a quarterdeck

shelter, in which they might be as protected from shot and musket-fire as those on the decks below them? Was self-exposure so central a part of the code of honour that a sailing ship-of-the-line, governed as these were, would not in fact have been operable in battle without it? It may be, at some subliminal level, that this self-sacrificial style of command also fed into the fighting capacity of ships. If his officers were prepared to expose themselves to so much danger, then what could a man do but follow their lead? It is precisely the opposite of generals commanding later battles from many tens of miles behind the front. Here the commanders placed themselves on the point of the spear.

It was not a complicated method, it was inherently bloody and it meant that officers needed to wait in the danger zone for long periods while the great guns did their work. That long period of exposure was an inescapable part of the theatre of battle. They had no protection, beyond the hammocks in their netting containers on either side of the quarterdeck, and the horizontal nets drawn taut above their heads to save them from falling debris. Neither was any use against roundshot, langridge or musket-fire. And the theatrical role played by honour, combined with the style of personal leadership Nelson had developed, meant that neither he nor any other officer could hide. Exposure of the person was more than an inherent hazard; it was an essential part of the task.