Midnight and the Meaning of Love (31 page)

Read Midnight and the Meaning of Love Online

Authors: Sister Souljah

It was a fort of ammunitions. There was a large gun lying against the wall, but I wasn’t familiar with the brand. Then my mind skipped ahead.

She wanted me to see all this for a reason

, I told myself. “Chiasa,” I called her. She turned and faced me. I pointed out the gun with no words or hands, only my eyes.

“Just a tranquilizer gun. You know in Japan, we have some wild-life. Seriously, we have bears,” she said with a half smile. “I got it from my grandfather. I borrowed it,” she said casually.

“Yeah,” I acknowledged. “What about that? I saw you with that at the airport.” I pointed.

“It’s a

kyudo

bow.” She turned toward me and stepped in and blocked the only entrance to the shed.

“

Kyudo

?” I asked.

“You know, like a bows and arrows kind of thing.” She positioned her arms and hands as though she were aiming and shooting one. However, the bow in her shed was the largest I had ever seen. She stepped up and unzipped the case, revealing the dynamic weapon. As quickly as she showed it, she zipped it back up.

* * *

I put my duffel bag up against the wall, right below some handcuffs that hung on a nail and across from some old nunchucks, also lodged on the wall. Beside several stacked storage boxes were a few pairs of mountain boots of different styles. On a nail were some rain ponchos. On the floor was about thirty feet of coiled colorful climbing rope. In addition to a well-used industrial-sized flashlight, there was a megaphone. When I saw some walkie-talkies, I stepped closer to them. “We can use them,” she said excitedly. The rest of the items Chiasa had in there were all inside cases. There were three long cases made of a thick blue cloth with wicked white kanji painted on. There was only a flap and blue string tying down the tips of the cloth cases.

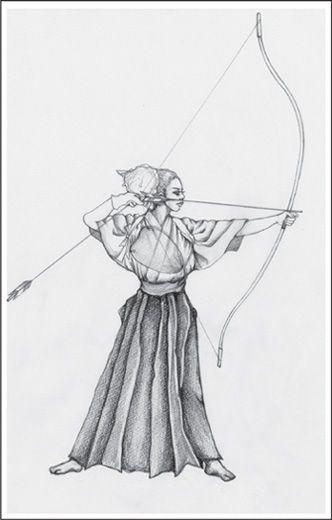

Chiasa and her

kyudo

bow and two arrows.

“My swords,” Chiasa said. “Old ones.”

I looked at my watch and saw that it was 10:15 a.m. “Let’s go,” I told her, stepping forward so that she would step out. I pulled the door closed, noticing that it swung out and in like an American door, instead of sliding sideways. I padlocked it and dropped the key into my pocket.

“My father built that for me. My grandfather’s metal shed was always here. But when I came here to stay with him, my father built this one.” She was speaking softly, more like she was talking to herself or moving with a memory. I remained silent, deciding right then and there that she was the first gift of Ramadan on the first day of the fast. She was my sentinel, which Sensei said every ninja on a mission should have.

When we reached the front of her house, she said,

“Chotto matte.”

She bent down and removed her kicks and placed them together on the corner of the step. She entered her house, leaving me standing outside. I liked that she didn’t ask me inside while her grandfather was not home.

But I didn’t like her clothing change. Chiasa emerged wearing a dark blue miniskirt, a light blue blouse, and socks, and carrying penny loafers.

“Why the change?” I asked.

“Everybody knows that a girl in a school uniform can get anything she wants in Japan. So you should just look at this as my costume. You’ll see,” she said, without flirtation. As she kneeled to put on her shoes, I felt uneasy. She had a book bag, the strap resting on one shoulder and pressing across her breast and down to her opposite hip, where the bag rode. She had a second strap crisscrossing the same way. She

pulled it off and over her head and handed it to me. She opened her book bag and pulled out a box.

“Welcome to Japan,” she said, handing me the items. The army green canteen was filled with liquid. I opened the box. It was filled with perfectly sliced and neatly arranged fruits. “You must be hungry. You didn’t eat,” she said, smiling.

“Thank you, Chiasa. I should’ve told you. While I am here visiting Japan, I’ll be fasting during the day, from sunup to sunset,” I confided.

“For the whole week?” she asked, incredulous.

“For the whole month,” I said solemnly.

“Why?” she asked.

“I’m a Muslim. This is a holy month for us,” I said. She stood silent; her gray eyes widened some and one of her eyebrows lifted. She paused, thinking.

“That’s so fucking cool,” she said softly to herself. “I like that. Then I won’t eat or drink either. We’ll both eat together at sunset.”

* * *

After switching train cars and going three stops, we arrived at Ginza. We walked a while, through well-constructed, clean, and well-lit underground tunnels. The tunnels were so dope to me. It was clever to be moving underground, beneath the city. They stretched a distance and were not hot stinky, crowded holes in the earth like the subway system of New York, where the rats raced. We reached a steep sequence of stairs leading us up and out into what had to be the heart of Ginza.

From Shinjuku to Yoyogi to Ginza there was a quality leap, I swiftly noted. The other two prefectures were definitely not low-quality, but Ginza was obviously high-quality, like Fifth Avenue in New York or Fifty-Seventh Street, but better, cleaner, and more attractive and elegant. I could see that the top designers of the world had their flagship stores located here. This place was about big business and buildings and billboards, as multinational corporations squared off to see which one could post its name and logos up the highest with dominating widths. In between the corporate wars were unique Japanese boutiques and tailors and haberdashers and upscale restaurants and bakeries and art stores and timepiece workshops and retailers and acupuncture lofts and therapeutic massage spas and ice creameries and yogurt dens.

I got drawn in by an astronomy shop with impressive telescopes and powerful lenses. I had never owned one but the design of the shop and display of the unusual equipment caught my eye. It was an awesome concept and invention, a lens that brought beautiful shining stars close to the eye of the human holding the piece of equipment.

Every single car on the street seemed brand-new. The few that weren’t were so well cleaned and polished and free from dents and blemishes that they blended in. In Ginza, there wasn’t only a handful of hustlers riding large like back in Brooklyn. The whole prefecture of Ginza was bubbling with limousines, Crown Victorias, Benzes, Rolls-Royces, Mazeratis, and Lamborghinis.

The streets were wide and clean and free of potholes. The traffic was at a bare minimum and the flow of people was orderly but steady. Men wore suits, tweed jackets, linen, spring suedes, and comfortable cottons. Some rocked ascots, Gucci, Louis Vuitton, and Yves Saint Lauren belts and briefcases, designer ties or expensive traditional silks, robes, and slippers. Business shirts were crisp and ironed. The absence or presence of cufflinks and of course the quality of the silver, gold, and platinum ranked them, one from the other. Not one shoe was run-over or cheap, from the workers to the execs.

Women were almost unanimously dressed in expensive, well-tailored clothes of every style from both the European and Asian continents. There were fine silks and lace and cotton and linens, and even their denim was threaded better, cut better, styled better, the material a deeper blue and more durable-looking.

As we walked further, my eyes cast down only to be introduced to a high-heeled heaven. Every feminine shoe seemed an expression of personality and poise and even preference. Each lady in front of me and moving past me was petite. Here in Tokyo, “fashion model slim” was not relevant. In Ginza, every female of every age was slim and sleek and flowing with a unique style of her own that made it difficult to determine a trend.

It wasn’t long before I realized that I had not seen any white people, Americans or Europeans. I’m not saying that there were none here, but I didn’t see ’em. So many people, and each face clearly Japanese. Whether I glanced at the workers in the stores, the people in the streets, the executives moving about, the money earners, money spenders, the owners, buyers, or sellers, the limo drivers or limo passengers

or even the window cleaners, they were all uniformly Japanese. This was Japan, and everything I saw confirmed that this was clearly their country!

“This whole area is Nakamura Plaza,” Chiasa said, as she stopped walking and gestured. “The building with the exact address that you are looking for is there across the street,” she pointed. “And the guy whose name you had on the paper, Naoko Nakamura, he should be there on the top floor.” She had her finger pointed toward the sky. “Let’s go,” she said confidently.

“Hold up,” I told her.

As I stood stiff, she said, “The paper you showed me said Naoko Nakamura, and this is Nakamura Plaza and over there is the Nakamura building. Usually here in Japan, the most important people have their offices located on the top floor of an office building or in a penthouse or co-op or condo. Isn’t it the same in New York?” she asked innocently. I didn’t answer, was no longer focused on her or her voice.

Looking up toward what I counted as the thirty-third and top floor, and then beyond into the white cloudless sky, I inhaled and wished that I was fighting this fight using my father’s mind—instead of my own. I needed to be backed up by my father’s empire and assets. I needed my father’s ingenuity and access to the world. I exhaled, my mouth drying some from the start of the fast. What would be my next move? What would my father do in this scenario that I was facing? What would my father advise me to do now? I felt like the black king on the chessboard with no frontline defense—no pawns—and no sideline defense—no bishops, no rooks, no knights. Meanwhile Naoko was chilling, the white king piece. Although his queen was dead—his wife, who was also Akemi’s mother—his knights, bishops, and rooks, and a billion pawns in his multimillion-dollar establishment were still securing him and assuring that he appeared monumental with an untouchable monopoly over my wife and his empire.

“What’s the plan?” Chiasa asked cautiously.

I turned my head in the opposite direction from where she was standing only to see a pack of teens and what I assumed was their chaperone gathered on the same side of the Nakamura building. An idea was forming.

“Do you know how to work the camera?” I asked her.

“I will in thirty seconds,” she answered. I handed it to her. She studied it. “Okay, I got it,” she said softly. “Let’s go make a movie. You be the director. I’ll shoot whatever you want me to shoot.” She smiled.

“Follow them in,” I said, using my head nod to point her eyes in the direction of the schoolgirls.

“But we are wearing different school uniforms,” she protested immediately.

“I didn’t say join them. Just follow them in. See if they are getting any kind of tour of the building. See if they give them any private information. If they do, you get it also. Use the camera to film the inside of the lobby—and everything that is going on.”

“But what are you looking for?” she asked.

“I need a printout of the building directory. Like the staff list. I need you to get in the parking deck. You can read the signs. Act like you’re lost. Find the executive parking and film the cars and plates of the executive vehicles.”

“You’re not going to do anything crazy, are you, or illegal?” she asked defiantly. Before I could answer, she added, “ ’Cause if you are, my fee has to be raised to the tenth power.” She smiled, but I knew she wasn’t joking. She seemed to want to let me know, in some subtle way, that she was down for whatever as long as she was dealt with fairly and paid her asking price. She didn’t have to worry. I would treat her right, naturally. Besides, I would not forget about her father; I didn’t need two madmen trying to destroy me at the same time.

“Nothing crazy, nothing illegal. I’m just collecting information. I’m just looking for something,” I told her solemnly.

“Are we looking for the girl whose little feet fit in those hundred-thousand-yen heels?” she asked straight-faced. I didn’t answer. “That gotta be it,” she said coyly. “Don’t worry, I’ll get it done.” She left with the camera in hand and the power button on and the red record light all lit up.

As I stood thinking in the midst of the moving crowds, I believed I heard my father’s response to my frustrated call for guidance. The volume of the comings and goings of Ginza dropped down. I could only hear him. My father said to me, “Naoko Nakamura is an Asian elephant, known for his wisdom and intelligence. He’s too large to confront or directly charge into. He is mammoth. He’s someone you’ve got to go around. Stay out of his area or you’ll set off a stampede.

Lay low in the tall grass. Give him the day. You take the night.” And his voice left as swiftly as it arrived.

So it was decided. I would not enter Naoko Nakamura’s building to demand to meet with him and ask, “Where is my wife?” Or enter into any diplomatic display of etiquette and approval, as my Umma had suggested.

My eyes followed the skyline. Having turned three hundred and sixty degrees twice, I selected a suitable target building and began walking.