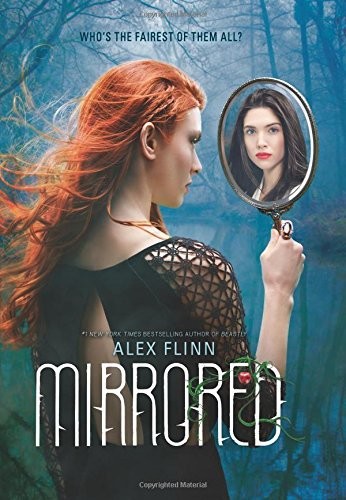

Mirrored

Authors: Alex Flinn

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Fantasy & Magic, #Family, #Stepfamilies, #Fairy Tales & Folklore, #Adaptations

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

..................................................................

Advance Reader’s e-proof

courtesy of

HarperCollins Publishers

This is an advance reader’s e-proof made from digital files of the uncorrected proofs. Readers are reminded that changes may be made prior to publication, including to the type, design, layout, or content, that are not reflected in this e-proof, and that this e-pub may not reflect the final edition. Any material to be quoted or excerpted in a review should be checked against the final published edition. Dates, prices, and manufacturing details are subject to change or cancellation without notice.

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

..................................................................

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

..................................................................

[dedi tk]

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

..................................................................

1982

I was a strange child. Strange looking, for certain, with buck teeth, red hair (and matching invisible eyelashes), a hooked nose, and barely the hint of a chin. My classmates at Coral Ridge Elementary teased me about these defects as if it was their God-given right. Maybe it was. After all, if I wanted to fit in, wouldn’t I just act more normal?

But even if I could change my hair, my nose, my chin, I couldn’t perform plastic surgery on my soul. Some secret part of me remained stubbornly different—brought egg salad when everyone else knew it was gross or used vocabulary words like

whimsical

, words no one else understood.

And shortly after my tenth birthday, I learned I was different in another way.

A special way.

That day, a rare, cold January day in Miami, I was walking alone on the playground. I had a jump rope. But when I’d asked the two girls who sat behind me, Jennifer Sadler and Gennifer Garcia, if they wanted to jump with me, they’d turned to each other with perplexed looks.

“Jump rope?” Jennifer’s blond ponytail swung from side to side as she shook her head. “Who jumps rope anymore?”

“We do in PE.” It was the only sport at which I excelled.

Jennifer rolled her enormous blue eyes. “Yeah, for a grade.”

“We could do something else then,” I said. “Kickball?” The Jennifers were part of a kickball game that included most of our class. I was never invited.

“Sorry, I think the teams are set.” Gennifer Garcia wrinkled her perfect nose.

As I trudged away, trailing my red-and-white-striped rope, I heard Jennifer say loudly, “You are too nice to that girl. It just makes her think she can talk to us.”

Gennifer laughed, then said softer, but still loud enough for me to hear clearly, “You can’t just tell people they’re freaks.”

“Why not? It would help her to know.”

Did being beautiful make you cruel? Were they really being cruel if I was so defective? And, if I were suddenly pretty, would I be mean too? Not that that would ever happen.

So I sat alone, shivering on a swing, looking at the toes of my navy Keds against the lighter blue clouds, when I spied a cluster of kids gathered around something. Ordinarily, I avoided unsupervised groups of my peers, but this particular group included, at its outskirts, one Gregory Columbo, a sensitive boy with coal-black hair and the warmest brown eyes I’d ever seen. Though he wasn’t exactly nice to me, he wasn’t mean. He was quiet, more the type to read a book than to play baseball. Now, he wiped at his eyes with his gray

sweatshirt sleeve. And something else made me gravitate toward the group, something I didn’t quite understand.

I jumped off the swing and went before I could chicken out.

“What’s everyone looking at?” I wanted to ask Greg why he was crying, but probably, he was pretending not to.

Greg turned away, touching the side of his face with his fingers.

“Greg?”

“Leave us alone, ugly.” Jennifer smirked. “It’s just a stupid, dead crow.”

Greg turned and I caught sight of his face. His cheeks and eyes were mottled red, like blotchy, red glasses, and I had a distant memory of him and a woman—his mother—standing outside his house, filling a blue bird feeder. Greg’s mother had died the year before.

The crowd was dispersing except for two boys, Nick and Nathan, who stood over the bird, poking it with a stick. I hated them. Hated. I could see the crow now, shiny and black as Greg’s hair against the dappled greenish-brown grass, one black bead of an eye staring at me. I stooped beside it.

“Eww!” Gennifer said. “Are you going to touch it?”

I glanced back to see if Greg was still there. Nick hovered over me with his stick. I fixed him with a stare.

“Don’t touch that. It’s disrespectful of the dead.” I remembered my mother saying something like that. Nick laughed and began to respond, but I said, “Go away.” I heard violence in my voice.

He backed away. “It’s dumb anyway.” Nathan and the Jennifers followed him off.

I reached down and touched the bird. It was not cold, not yet at least. But it lay as still as the airless day. Its licorice-black wings caught the light, reflecting green and purple. I felt the ground move with the thumping of my enemies’ retreating sneakers. I shivered, then slid my hand underneath the bird. It felt like leaves. I turned

my back to Greg. Then, I placed my other hand over it and picked it up. It was larger than both my hands, but it weighed less than air. I remembered someone, Greg maybe, saying in class that birds’ bones were hollow so they could fly.

Without knowing why, really, I raised the bird to my face, opened my hands, and blew.

The bird blinked.

No, it hadn’t. It was dead.

I stroked its smooth feathers. Behind me, Greg stood silent, but I could hear his breath. I found a tiny wound under the bird’s wing. When I touched it with my finger, it seemed to disappear.

The bird blinked again. This time, I was certain it had.

“Are you okay, then?” I barely whispered.

It cocked its head toward me. Behind me, I heard a gasp. Greg. I did not, could not look at him. I whispered, “Are you ready to go now?”

Again, the bird closed then opened its black bead eye, and in my head, I thought I heard it say, “Do you want me to?”

“Whatever you like. Your family is probably worried, though.”

“It was a boy,” the bird said, “the one with the stick. He threw a rock. It hurt. It

killed me.

”

“It didn’t kill you. You’re alive.”

The bird twitched its head. “It killed me. I was dead.”

I couldn’t understand this. “Hmm, maybe you should get away from him.”

“I guess so!” said the bird. “Can you help?”

“How?” I drew in a deep, shaky breath.

“Just . . . raise me up.”

I nodded, then stood, still holding the crow in both hands. I lifted it high above my head.

It rose, shifting first to one clawed foot, then the other. It spread its black wings toward the graying sky. They gleamed purple and

green in the strained sunlight. It fluttered, then lifted into the air. I watched it until it was merely a small, black speck against the clouds. I turned toward school.

“Hey,” a voice said behind me. “That bird was dead.”

Greg. I looked up to where the bird had been. “No, it wasn’t. It flew away.”

“But it was

dead.

”

“No.” It seemed, now, very important for me to impress this upon him. After all, I could barely believe what I’d done myself. It couldn’t have happened, but it had. “No. It was only scared. Nick hit it with a stick. It’s okay now.”

Greg glanced at the ground. I did too and saw an irregular puddle of blood, mixing with the dusty dirt. “Okay,” he said finally.

“We’re going to get in trouble,” I said.

“I’ll tell Ms. Gayton what happened, that you helped the bird.” His eyes were just nice looking, the way his eyebrows came down in the center, all concerned.

I shook my head. “She won’t believe you.”

“She will. Teachers like me. They feel sorry for me because of—”

“Your mom.” I was thinking they liked him because he was so cute, those big eyes.

He nodded. “I can get away with anything.”

“They hate me.” It was true. Even though I aced every test, teachers had no smiles for me. They liked the prettier girls, the ones who didn’t care about learning but only copied one another’s homework.

“I’ll tell her you were helping me then,” he said.

I thought about it. “Okay.”

We began to walk. As we did, my hand brushed Greg’s. I wanted to grab it, but I didn’t.

He said, “That was pretty cool.”

“I didn’t do anything.”

“You did.”

“No.” I said it too loudly, too emphatically, then regretted it. I sounded like I was lying. “I’m sorry, but the bird was probably just shaken up or something. I mean, it flew away like nothing.”

I remembered the wound under its wing, the wound that had closed.

How

had it?

Greg shrugged. “Okay.” He started up the stairs to the school building, taking them two at a time, keeping ahead of me. He thought I was weird, though I’d tried so hard to prevent it, though I wanted him to like me so much. I’d have done anything to make him like me. Anything.

I didn’t speed my step. What would be the point? As I trudged along, I felt something, like a pair of eyes, peering at me through the trees. I looked back and saw a shadowy figure dressed in green like the leaves. Or maybe it was the leaves. I shivered, remembering what my mother had said about perverts who lurked on playgrounds, waiting for children alone.

“Hello?” I said.

No answer except a riffle of wind across the grass and my own footsteps.

I stopped, glanced back. No one there. A caw, maybe the same crow, echoed from the treetops. I felt each individual hair on my arms stand on end. My feet planted on the ground.

Finally, I ran after Greg to the school building.

Nothing unusual happened for a year or so. Maybe I made nothing happen. But then, one day something did. Something that changed everything.