Miss Clare Remembers and Emily Davis (36 page)

Read Miss Clare Remembers and Emily Davis Online

Authors: Miss Read

At the end of the year, she was relieved to know that her work had been considered satisfactory. She was asked again if she would take the 'small' class of forty backward children, and agreed.

And so it came about that one September morning she faced her new class. Most of the six-year-olds were backward because of absence from school through illness. Some were mentally unsound and a few of these children would become certifiable at the right age. Some were incorrigibly lazy and would always lag behind, and a few were rebels by nature against any sort of discipline and authority, and likely to remain so for the rest of their lives.

Jane grew very fond of them. For one thing, they were grateful for any effort made for them. They were wildly delighted with such simple creations as a paper windmill or a lop-sided blotter, and carried these treasures home with far more care than their more brightly endowed fellows. They were affectionate and anxious to please. Jane found their goodwill exceedingly touching.

She also found them exceedingly exhausting, and returned home each evening tired to death. She had no heart for any sort of social life. Early bed was the thing she craved most, and her mother grew alarmed.

The family doctor prescribed iron tablets and sea-air. The iron tablets were taken regularly and seemed to do some good. Sea-air was more difficult to come by. The family had no car, and money was still short.

When, in February, Jane was forced to take to her bed with influenza and was unable to leave it for three weeks, the doctor spoke his mind to Mrs Draper.

'That girl of yours upstairs,' he told her frankly, 'is wearing herself out. She's no reserves of strength at all. See she gets a holiday by the sea, after this, and then a teaching post that's easier than this one. Don't you know any school that has small classes?'

The Drapers did not. But during the summer term, when Jane was back at school and still struggling feebly with her forty backward children, a post was advertised in

The Teachers' World

for an assistant mistress to take charge of eighteen infants at Springboume School.

'Number on roll,' said the advertisement, 'forty-eight.'

A whole school, with only forty-eight, thought Jane longingly!

She looked up the village in the ordnance survey map. It was, she saw, a few miles from Caxley where one of her college friends lived.

She wrote to her, and asked for her advice and for any information.

'Come and see it for yourself,' was the answer, and with a glow of hope Jane went to spend the weekend with the Bentleys.

They were a happy-go-lucky family living on the northern outskirts of Caxley, some three miles from Springboume. To reach the village the two girls cycled along a quiet valley

beside a little river full of water-cress beds. It ambled along sedately beneath its overhanging willows on its way to join the Cax.

It was a Saturday morning, warm and sunny. The school, of course, was uninhabited and so was the school house, for Emily had gone on the weekly bus to do some shopping in Caxley.

Emboldened, the two girls pressed their noses to the classroom windows and gazed at the interior. To Jane it seemed like a dolls' school after the enormous building in which she taught. She caught a glimpse of a large photograph of Queen Mary as a young woman, wasp-waisted in flowing white lace, with pearls in her hair.

The desks were long and old-fashioned, housing five or six children in a row. But there was nothing old-fashioned about the stack of new readers on the pianoâJane was using the same series herselfâand she noted, with approval, the children's large paintings, the mustard and cress growing in a shallow dish, and the goldfish disporting themselves in a roomy glass tank, properly equipped with aquatic plants.

The playground was large, and shaded by several fine old trees. Elder bushes, turning their creamy flowers to the sun, screened the little outhouses which were the lavatories.

It all seemed cheerful and decent, a kindly spot where one could be happy, and could work without heart-break.

When Jane returned, she applied for the post and was accepted. Later that summer she met her headmistress-to-be for the first time.

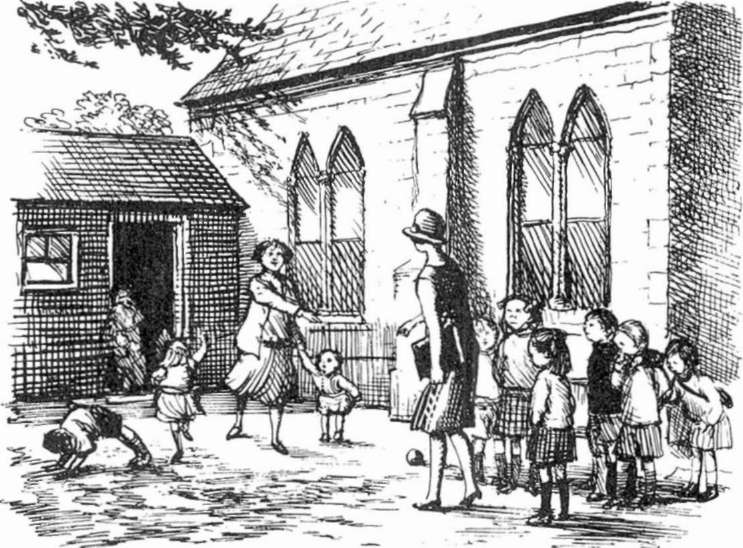

She was in the playground carrying a tear-stained five-year-old in her arms. She kissed it swiftly before putting it down, and advanced to meet Jane. It gave Jane quite a shock. Would Miss Jolly do that?

'I'm so glad you can come and help us next term,' said Emily Davis, holding out her hand.

And, as Jane held the small warm brown one in her own, she felt that, at last, she had come home.

T

HERE

began then for Jane a period of great happiness and refreshment which was to colour her whole life.

To begin with, she stayed with the hospitable Bentleys, for the first few weeks of the autumn term, until she could find suitable lodgings nearer the school. After so much ill-health and strain, it was wonderful to be taken into the heart of such a cheerful family, and Jane thrived.

The bicycle ride to school and back brought colour to her cheeks, and an increased appetite. In those first few weeks of mellow autumn sunshine, Jane began to realise the loveliness of the countryside.

Harvest was in full swing, and the berries in the hedges were beginning to glow with colour. The cottage gardens were bright with Michaelmas daisies and dahlias, and the children brought sprays of blackberries and early nuts for the classroom nature table. Sometimes Jane received fresh-picked field mushrooms which the children had found on the way to school, or a perfect late rose from someone's garden.

She revelled in the bracing air of the downs and, encouraged by her headmistress, took the infants' class for nature walks round and about the village.

She found the children amenable and friendly. They might lack the sharp precocity of her former town pupils, but their slower pace suited Jane perfectly. Facing a class of eighteen, after forty or fifty, was wonderful to the girl. There was so little noise that there was no need to raise her voice. She could hear each child read dailyâa basic aim she had never been able to achieve beforeâand found the children's progress marvellously heartening.

Of course there were snags. The chief one was the range of ages. The youngest was not yet five; the oldestâand most backwardânearly eight. But Jane was used to working with groups, and found that discipline was no bother with so few children who were mostly of a docile nature. Relaxed and absorbed, Jane's confidence in her own abilities grew steadily, and she became a very sound teacher indeed.

Emily Davis played her part in this process. Jane found her as quick and energetic as Miss Jolly had been, but with a warmth of heart and gentleness, both lacking in her former headmistress.

Emily was like a little bird, Jane thought, with her bright eyes and brisk bustling movements. The children loved her, but knew better than to provoke her. They knew, too, that a cane reposed at the back of the map cupboard. No one could remember it being used, but the bigger boys, who occasionally assumed some bravado, were aware that Miss Davis was quite capable of exerting her powers, if need be, and kept their behaviour within limits.

Emily's high spirits were the stimulus which these children needed. Mostly the sons and daughters of farm labourers, they were unbookish and inclined to be apathetic.

'Don't forget,' said Emily to Jane one playtime, as they sipped their tea, 'that most of them are short of food, and quite a number go cold in the winter. Times are hard for farmers and their men.'

'But they look well enough,' observed Jane.

'Their cheeks are pink,' answered Emily. 'If you live on the downs you soon get weather-beaten. And by the end of the summer they are nicely tanned. But look at their bodies when they strip for physical training! You'll see plenty of rib cages in evidence. There's just as much poverty in the country as in towns. The only thing is it's not quite so dramatic, and fewer people see its results.'

There were such families at Springbourne, Jane soon discovered. She saw too how Emily coped practically with the situation, supplying mugs of milky cocoa during the winter to those who needed it most. Those who did not run home for their midday meal brought sandwiches, for this was before the coming of school dinners. One family, in particular, was particularly under-nourished. When the greasy papers were unwrapped, they were usually found to contain only bread with a scraping of margarine.

Many a time Jane saw Emily adding a piece of cheese to this unpalatable fare, and apples from her store shed. It was all done briskly, without sentiment, and in a way which would not make a child uncomfortable.

It was small wonder, Jane thought, that Emily Davis got on well with the parents. There were exceptions, of course, and one incident Jane remembered for years.

It happened just before Christmas one year. Emily had arranged a school outing to a Christmas pantomime, put on by amateurs, in Caxley. A bus was hired, and the fare and the entrance fee together would cost five shillings. Parents could join the party, and there was a good response, despite the fact that five shillings seemed a great deal of money to find just before Christmas.

The fact that several Thrift Clubs would be paying out about that time may have accounted for the enthusiasm with which Emily's venture was received. The money came in briskly until only young Willie Amey's contribution, and his mother's, were outstanding.

The day before the outing, Mrs Amey appeared, in tears. Asking Jane to keep an eye on both classes, Emily took the weeping woman over to the school house and heard the sad tale.

'That beast of a husband,' Emily told Jane later, 'took the ten shillings from the jug on the top shelf of the dresser, where she'd hidden itâor

thought

she had, poor soulâand drank the lot at the pub last night.'

'What will happen?'

'I shall put in the money for them,' said Emily shortly, 'and I'll see Dick Amey myself. He'll pay up, never fear!'

Jane gazed at Emily in trepidation. Dick Amey, she knew, was a big, burly, beery fifteen-stoner. Jane was afraid of him under normal circumstances. Provoked, he could be dangerous, she felt sure.

'But he's such a great

bully

of a man,' said Jane tremulously.

'And like most bullies,' said Emily forthrightly, 'he's a great coward too. I shall square up to him tonight.'

She went about her duties as blithely as ever that afternoon, but Jane was the prey of anxiety. She said goodbye to her diminutive headmistress that afternoon, wondering if she would see her unscathed next morning.

She need not have worried. Evidently Emily had put on her coat and hat as soon as she thought Dick was home, and had climbed the stile, crossed a field to his distant cottage, and tapped briskly at his door.

His frightened wife stood well back while the proceedings took place.

Emily had come straight to the point. Direct attack was always Emily's motto, and she got under Dick Amey's guard immediately.

'About as mean a trick as I've ever heard of said Emily heartily. 'But the money's in for both of them and they're going to enjoy the show. That's ten shillings you owe me. I'll take it now.'

Dick Amey, flabbergasted, demurred.

'I ain't got above two shillun on me,' protested Dick.

Emily held out her hand in silence. His wife watched in amazement as he rooted, muttering the while, in his trouser pocket and slammed a florin into the waiting palm.

'When do I get the rest?' said Emily.

'You tell me,' growled Dick.

Emily did.

'A shilling a week at least, till it's done,' said Emily. 'You keep off the beer for the next few weeks and you'll soon be out of my debt.'

Jane heard of this memorable encounter from Mrs Amey herself, long after the event. It must have looked like a wren challenging an eagle, thought Jane. But, no doubt about it, the wren was the victor that time.

***

Jane found permanent accommodation in a tiny cottage on Jesse Miller's farm at Springbourne.

It had been empty for some time, but was in good repair, for the Millers were always careful of their property.

It consisted of a living room and kitchen, with two small bedrooms above. The place was partly furnished and Jane had the pleasure of buying one or two extra pieces to increase her comfort. The rent was five shillings weekly, and the understanding was that if Jesse Miller needed it for a farm worker sometime, then there would be a month's notice to quit.

She was now a near neighbour of Emily's, and frequently spent an evening with her headmistress and old Mrs Davis who now lived with her. Emily's father had died some years before and it had taken much persuasion to get her mother to leave the family cottage at Beech Green where she had reared her large family. But at last she consented, and had settled very well with Emily.

The two had much in common. They were both small, energetic and merry. Jane found them gay company, and often looked back, in later years, upon those cheerful evenings when the lamp was lit and stood dead centre on the red serge tablecloth, bobble-edged, which Mrs Davis had brought from her old home.