Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting (20 page)

Read Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting Online

Authors: W. Scott Poole

During the same period that the evolution controversy became a permanent part of American cultural life, a fear of “primitive races” and the horrors of racial amalgamation came to represent a significant theme in the work of H. P. Lovecraft, one of the most influential authors of horror fiction in American history. Lovecraft’s tales of horror, written between the early 1920s and his death in 1937, became, as Phillip Schreffler puts it, “virtually synonymous with the weird tale.” They also reflected deeply racist sentiments born of the paranoia that Anglo-Saxon civilization faced threat from “primitive civilizations.”

47

Lovecraft published some of the most influential stories of horror in American literature, primarily though the pulp magazine

Weird Tales

. Some of these are stand-alone narratives, written quickly to please his audience and receive a royalty check (including his 1922 “Herbert West—Reanimator” the basis for Stuart Gordon’s “Re-Animator” films of the 1980s). Many of Lovecraft’s other tales are more sophisticated

and have been referred to by later admirers as “the Cthulhu mythos,” Lovecraft’s mythology that tied together a number of his stories. In this horrifying cycle of tales, Lovecraft imagined a cadre of powerful alien beings, known as “the Old Ones,” who had once inhabited the earth. Human beings had been ruled by these old ones until the beings lapsed into a long sleep.

Lovecraft’s horrors often center on human beings in the present who seek to use horrid rituals found in the occult grimoires, like

The Necronomicon

, to raise transdimensional monsters from their cosmic sleep. Lovecraft usually pictured these rituals being performed by what he called “the dark peoples of the earth” and taking place either in foreign locations or American seaport cities with a population heavy with the immigrants the author himself personally detested. His heroes, on the other hand, tend to be bookish, bespectacled Anglo-Saxons of Puritan descent, New England Van Helsings who seek to destroy the foreign Draculas.

Lovecraft’s “Call of Cthulhu” provides an example of this tendency. A New England scholar of good Puritan stock begins to fear that the ancient being Cthulhu has been awakened when black “swamp-cult worshippers” near New Orleans and “degenerate Esquimax” in Greenland are found to be engaged in strange and exotic rituals. Those who take part in the dark occult rites are described as “half-castes and pariah” or “hybrid spawn.” Human beings, at least of a “degenerate type,” are some of Lovecraft’s greatest monsters.

48

Outside of his writing, Lovecraft frequently made clear his own conceptions of racial difference. During a brief residence in Brooklyn in the late twenties, Lovecraft spewed a torrent of racist venom at his correspondents. A visit to New York’s Lower East Side led him to describe the immigrants he found there as “slithering and oozing in and on the filthy streets.” He called New York itself “a scrofulous bastard city” and the immigrant communities there a “degenerate gelatinous fermentation.”

49

Given the melodramatic nature of these rants, it is difficult to know how seriously to take Lovecraft’s comments on immigrants. Lovecraft had a strangely divided mind over such matters given that he lived in Brooklyn for a time because of his marriage to a Jewish woman (a marriage that went badly, undoubtedly fanning the flames of his prejudice). However we understand the undeniably great writer’s personal prejudices, the idea of racial monstrosity certainly played a key role in his literary output, mirroring the connection between race and monstrosity in the broader American culture. Lovecraft himself claimed that his “The Horror at Red Hook” had been inspired by the “

evil looking foreigners” he had seen in Brooklyn. White America largely shared Lovecraft’s view of allegedly evil-looking foreigners. This was especially true in the wake of the post-World War I “Red Scare,” a national hysteria that painted every Italian laborer or Jewish tailor as a bomb-throwing anarchist. The revivified Ku Klux Klan became an open and respectable organization in the 1920s, using their tactics of intimidation against immigrant communities as frequently as against African Americans. Lovecraft’s fiction described horrors that many white Americans believed in firmly, the horror of “degenerate” foreigners.

The Scopes Monkey Trial suggested that two cultures had emerged in America but also that belief in monsters could be found on either side of the divide. Antievolutionists worried that Darwin’s theory amalgamated them with monstrous races, while the more scientifically inclined assumed that the racially pure Anglo-Saxon had risen above the world of the monstrous. The terrors of both mind-sets are put in sharp relief in Lovecraft’s tales of horrors from the earth, horrors evoked by the “hybrid spawn” of the degenerate. In the first half of the twentieth century, American monster stories became tales of forbidden interminglings, of sex, and of terror. Miscegenated monsters threatened the neat divisions on which middle-class American life depended, and anxiety over racial chaos grew out of interrelated anxieties over sexuality.

White Girls in Danger

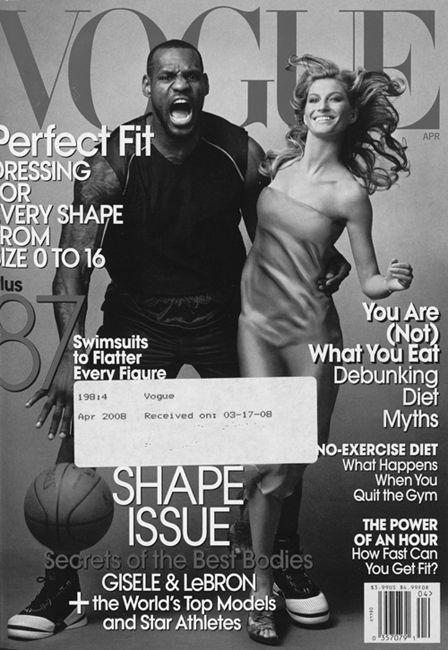

The April 2008 issue of

Vogue

magazine featured only the third African American celebrity to appear on its cover since its founding in 1914. It was an appearance not without controversy. The photograph represented basketball star LeBron James unloosing a savage and ferocious cry, while in his arms he grasps the white model Gisele, who pantomimes screaming terror (though with a smile). Obviously making use of the imagery of King Kong and Fay Wray, the picture set off a firestorm of controversy that reminded observers of the secret history of racial imagery in America and its tendency to transform African American men into monsters with white female victims.

50

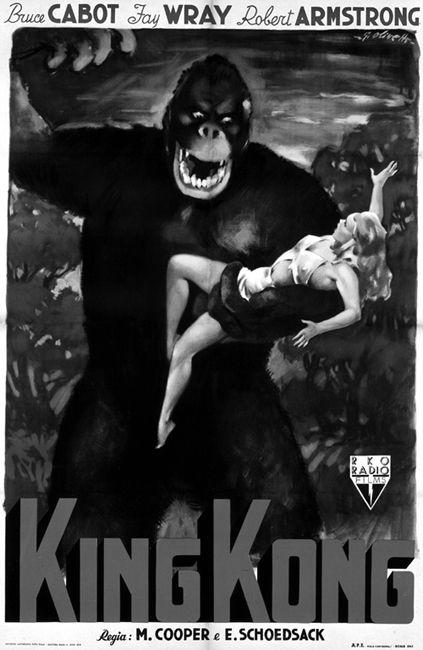

King Kong

(1933) readily made use of white supremacist imagery, tapping into centuries of white folklore about Africans and apes and the alleged hypersexuality of black men. Certain aspects of the narrative remind us how often America’s monstrous metaphors are uncomfortably close to historical reality. The captured Kong who dies in captivity shows a certain similarity to Ota Benga’s story. Its use of the symbolisms of African American men, sexual desire for white women, and folklore about monster apes tapped into racist roots going centuries deep in the American experience.

51

LeBron James and Gisele. Cover of

Vogue

(April 2008).

King Kong

Movie Poster with Fay Wray.

The 1933

King Kong

tells the story of a director, Carl Denhem, who wants to shoot an adventure film on Skull Island off the coast of Africa. He takes with him Anne Darrow, a willowy white waif played by Fay Wray. On the island, Denhem and his film crew meet a vicious and possibly cannibalistic tribe that conforms to every colonialist stereotype of African people. Like Lovecraft’s cultists, Skull islanders worship a giant, monstrous being, an ape that Denham and his crew capture and take to New York in chains as an ethnographic spectacle. Kong escapes and whisks away Darrow, whose screams provide the soundtrack for much of the rest of the film. The great black beast rampages through New York until brought down in the unforgettable scene at the Empire State Building. In the final frame, Denham delivers the famous line “’Twas beauty killed the beast.” The uncontrollable, and twisted, desire of the creature for a white woman became his downfall.

52

At a time when the American public had the racialized images of the Scopes Monkey Trial freshly in their minds, the story of King Kong carried a clear racial subtext. Fay Wray reincarnated D. W. Griffith’s unlucky Flora, an endangered white woman not only chased but this time seized by the monster. Screen audiences throughout much of the country would have been used to hearing their politicians and preachers refer to African American male criminals as “black beasts” and “black fiends” and insulted as “ape-like” and “monkeyish.” At the end of the day, as contemporary film critic Jim Pinkerton points out,

King Kong

is the story of a “flat-nosed black being brought from Africa in chains” who attacks a white girl. Notably, the 2005 Peter Jackson remake placed Skull Island in an undetermined Pacific location and not in Africa in a clear attempt to tamp down the story’s glaring racial symbolisms.

53

King Kong

was not the only monster film that reflected white America’s tragic obsessions. Both of the classic Frankenstein films employ imagery in which the monster endangers white womanhood. In the original film, the monster comes upon a frail young girl throwing lilies into a pond. In his desire to play with her, the monster flings her into the water, killing her. The distraught father carries her in his arms to the town mayor in a scene reminiscent of Flora’s father carrying her after the death at the hands of the “black monster” Gus in

Birth of a Nation

.

54

Frankenstein

does not simply rely on carefully coded messages. When the monster enters Elizabeth’s bedroom and corners her, all we hear are her screams as the camera cuts away. When rescuers rush into her room, the monster has gone and she lies on the bed, moaning incoherently, her flimsy nightgown looking torn and disheveled. As historian

Elizabeth Young notes, this scene is “framed precisely according to the imagery of interracial rape.”

55

In

Bride of Frankenstein

, the monster bends over yet another defenseless young girl to try to save her from drowning, an action perceived as a sexual violation by an angry lynch mob. Elizabeth Young points out that, in the film’s famous final scene, even the monster’s offer of affection to “the Bride” can be read as an encoded anxiety about sexual threat to a white woman. Young notes that “the Bride” is filmed glaringly white over against the discolored, almost muddy, image of the monster. She is, in fact, wearing the same gauzy robes as Elizabeth in the first film. Her fate (she willingly dies by fire rather than give herself to the monster) again evokes Flora’s in

Birth of a Nation

, suggesting that death is preferable to sexual violation by “a beast.”

56

These images reflected anxieties over changing mores in sexuality and gender, as well as America’s continuing obsession with racial difference. Social changes in American society early in the twentieth century created some of the anxiety over what was labeled “the new woman.” Between 1880 and 1900 the number of women employed in the emerging industrial economy doubled. Although much of this new work force entered traditionally female fields (such as nursing and domestic work) the rise of American business enterprises called forth an army of bookkeepers and stenographers just as the emergence of American retail demanded “shop girls.” Conservative voices warned that such changes boded ill for American society, threatening the collapse of the family and encouraging sexual license for women.

57

By the 1910s urban folklore circulated about “white slavery rings” operating in America’s urban areas, kidnapping innocent Anglo-Saxon women fresh off the farm and debauching them in prostitution rings. Progressive reformers, churches, and even urban police chiefs gave this folklore the legitimacy of their authority and influence. Reformers insisted that by 1910 tens of thousands of women were being whisked away into forced prostitution, almost always by suave foreigners or “brutish” African American men. Books with titles like

Chicago’s Black Traffic in White Girls

and

White Slave Hell

combined moral fervor with sensationalism. These lurid tales offered images of country girls gone bad and ignorant immigrant women taken in by vice. In a nod to America’s sea monster tradition,

White Slave Hell

featured “Vice” as a giant Lovecraftian creature, a “monster” whose “slimy tentacles drag in/the fairest forms to grace the dens of sin.”

58