Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting (22 page)

Read Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting Online

Authors: W. Scott Poole

By the 1960s Kligman had begun conducting research on his imprisoned subjects for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Harriet Washington notes that the most dangerous experiments conducted by Kligman involved the administration of high-risk drugs to inmates as a part of a long term CIA plan to produce a “the perfect ‘truth drug’ for interrogating Soviet intelligence operatives.”

72

The work of Washington and other scholars to expose these real-world monstrosities underscores the fact that monstrous metaphors in American historical life have a way of becoming real, that they are intertwined with attitudes and social structures that make the monster possible. The tendency to view American monsters as primarily psychological archetypes ignores how closely they have reflected actual historical events and actual historical victims. A significant segment of America’s history of science and medical research is a history of truly mad science. The monster seems more real than metaphorical for the thousands of victims of racist science.

Ignoring the monster when it becomes too real represents one way to deal with them. By the 1940s many Americans seemed to want to see a separation from the horrors on screen and the horrors of the “real world.” Films of the 1930s tapped into a variety of anxieties over sexuality and gender, race and science. By the 1940s, monster films disappeared into a fairyland of unreality and juvenile humor. Films like

Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man

,

House of Frankenstein

and

House of Dracula

cashed in on the famous monster’s celebrity in narratives with enjoyable, but thoroughly adolescent, plotlines.

Monster stories of the 1940s shared some very real similarities to the way Americans at home dealt with the Second World War more generally. Images of the war, even combat images, often sanitized the conflict. Author and veteran Paul Fussell has pointed out that although the instruments of death used in World War II tore and shattered bodies in horrifying ways, pictures of veterans unfailingly showed them whole and hale. Perhaps the “body horrors” of wolf men and reanimated

body parts represented a “return of the repressed,” stories about bodies deformed and shattered. More likely the monster stories of the 1940s became simplistic escapism, a denial of the truly monstrous.

73

Almost no references to the Second World War made it into the horror films themselves. Horror historian David Skal has commented that Chaney’s

Wolf Man

appears to be set in England in 1940, a place where, strangely, no one seems to know about the war but everyone knows about werewolves. Only one film, a Lugosi picture made for Columbia long after the King of the Vampire’s star had set, makes reference to the war.

Return of the Vampire

, one of the many awful films Lugosi made during this era, had a World War II-era vampire awakened by an exploding German bomb during the blitz only to be reinterred by another blitz attack in the final scene.

74

By the late 1940s America had seemingly tired of monsters. The end of the war also saw the end of the classic Universal monster cycle after its long period in decline. The 1948 film

Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein

is often seen as the definitive end point for the golden age of the monster mash. Farce had replaced fear. But popular culture in the United States, as well as folklore and religion, soon found new kinds of monsters to dread, desire, and seek to destroy.

The United States emerged from the Second World War with a broad sense of optimism. Having suffered the fewest casualties of the major powers, its economy booming with heavy industry, America seemed poised to create an imperium. Veterans, at least those of the race and class favored by American society, came home to prosperity unheard of in their parents’ wildest dreams. The atom bomb put enormous power into American hands, a power the U.S. government had shown itself willing to use against a battered Japan in 1945.

Portentous rumblings could be heard beneath the surface of this sunny landscape. President Harry Truman, heir of the enormously popular FDR, faced a challenge in the 1948 election from southern segregationists in his own party. The 1948 “Dixiecrat Revolt,” with its venomous use of race, represented a style of American politics that shaped the next sixty years of the country’s history. A year later, American intelligence operatives discovered that the Soviet Union had exploded atomic weapons. Fear of communist infiltration helped make paranoia a successful political strategy for the leaders of both major American parties.

Popular culture in the next two decades mirrored real American anxieties over the Cold War, communist subversives at home, the changing nature of American adolescence, and the American family, as well as ongoing concerns about race relations. But in these pop culture mirrors, most Americans saw the world only as they wished to see it. Horror and science fiction became escapist in the worst sense of the word. The monster films of the 1950s in particular told tales that reflected certain aspects of real-world anxieties but that also urged viewers to forget their anxiety and to trust the military, political, and scientific establishment to chase the monsters away.

—

“Lovecraft in Brooklyn,” The Mountain Goats

L

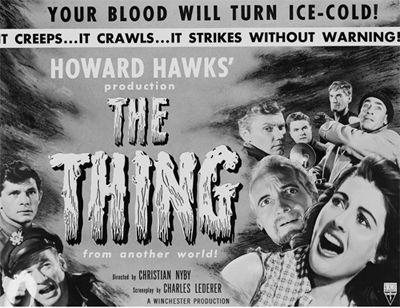

egendary producer and director Howard Hawks’ 1951

The Thing from Another World

featured a group of American scientists and military men at an arctic station who discover a giant craft frozen in the tundra. An Air Force captain suggests to the team that perhaps the craft belonged to the Soviets since “they are all over the Pole, like flies.” Attempting to extract the giant ship ends in its destruction, but the scientists and Air Force personnel manage to save a “Thing” trapped in a block of ice.

The escape of the Thing from its ice prison sets off a debate between Dr. Carrington and the Air Force officers. Carrington believes that the creature can be a “source of wisdom.” Unfortunately, the Thing turns out to be a bloodsucking creature, an extraterrestrial Bela Lugosi that the Air Force men have to destroy (though not before it does violence to Dr. Carrington when he tries to communicate with it). After the struggle with the alien is complete, a reporter uses the base radio to announce the perilous incident to all humanity: “Here at the top of the world a handful of American soldiers and civilians met the first invasion from another planet,” he says. Triumphantly telling his listeners that the Thing has been destroyed, he ends with a warning. “Tell the world. Tell

this to everybody, wherever they are. Watch the skies. Everywhere. Keep Looking. Keep watching the skies.”

The Thing from Another World

Poster

America in the 1950s lived in the shadow of the atom bomb. After the Soviet Union developed and tested atomic weapons in 1949, the possibility of a nuclear exchange between the two superpowers seemed both likely and imminent. J. Robert Oppenheimer, the scientist behind the Manhattan Project who publicly lamented his part in creating such a weapon, described the two nuclear powers as “scorpions in a bottle” certain to “kill each other.”

1

Americans in the nuclear age tremulously watched the skies much as the final lines of

The

Thing

had insisted. Most watched not for extraterrestrials, but for the sudden flash of an atomic weapon, the signal to “duck and cover” if they were not one of the families lucky enough to have a private bomb shelter. Many convinced themselves, with plenty of help from government and military officials, that a nuclear exchange was survivable, a war in which America would likely even come out on top.

2

American cold war culture represented an age of anxiety. The anxiety was so severe that it sought relief in an insistent, assertive optimism. Much of American popular culture aided this quest for apathetic security. The expanding white middle class sought to escape their worries in the burgeoning consumer culture. Driving on the new highway system in gigantic showboat cars to malls and shopping centers that accepted a new form of payment known as credit cards, Americans could forget about Jim Crow, communism, and the possibility of Armageddon. At night in their suburban homes, television allowed middle-class families

to enjoy light domestic comedies like

The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet

,

Father Knows Best

, and

Leave It to Beaver

. Somnolently they watched representations of settled family life, stories where lost baseball gloves and dinnertime hijinks represented the only conflicts. In the glow of a new Zenith television, it became easy to believe that the American dream had been fully realized by the sacrifice and hard work of the war generation.

3

American monsters in pop culture came to the aid of this great American sleep. Although a handful of science fiction films made explicit political messages that unsettled an apathetic America, the vast majority of “creature features” proffered parables of American righteousness and power. These narratives ended, not with world apocalypse, but with a full restoration of a secure, consumer-oriented status quo. Invaders in flying saucers, radioactive mutations, and giant creatures born of the atomic age wreaked havoc but were soon destroyed by brainy teams of civilian scientists in cooperation with the American military. These films encouraged a certain degree of paranoia but also offered quick and easy relief to this anxiety. Horror film scholar Andrew Tudor, after surveying the vast number of monsters raised and dispatched by science in the 1950s, concluded that such films did not so much teach Americans to “stop worrying and love the bomb” as to “keep worrying and love the state.”

4

America’s monsters did not disappear despite the best efforts of conformist 1950s culture. Popular culture produced monster tales that sought to rob monsters of their power, but a growing underground folklore of urban legend warned the nation that the monster might threaten the safe world of midwestern farms or suburban neighborhoods. America’s monstrous past even found its way into a post-World War II religious revival as communism and its agents became satanic monsters in the eyes of nervous Americans. And while millions of Americans turned to either to the Reverend Billy Graham or Bishop Fulton Sheen for spiritual succor, others sought out new religious movements that made monsters from beyond the stars into gods and explained the secret history of the world as a story of friendly alien invaders.

5

Mutant Horrors

Post-World War II America put aside its interest in some of the monsters of yesteryear. The sideshow declined in popularity during the 1950s, as did the freak show that had been its central attraction. The freak shows of Coney Island, for example, closed down in the late 1940s as real estate developers sought to “clean up” area attractions. In 1947 the

New York World

noted that “

freaks still attract curious stragglers on Coney Island midway” but also predicted “hard times ahead” for “the Mule Face Boy” and “the Turtle Girl.”

6

Reformers used the rhetoric of “human dignity” against the sideshow during this era. The increasing medicalization of human abnormality led to the institutionalization of many of the people who would have once performed as freaks. A few found their way into the new monster movies of the 1950s. The 1953 classic

Invaders from Mars

featured eight-foot-six Max Palmer (“the world’s tallest man”) in an unconvincing green velour mutant costume.

7

The sharp dip in the popularity of the sideshow freaks grew out of the desire of many Americans to escape the horrors of history in the aftermath of World War II by creating a safe and sanitized public culture. A number of historians have argued that advisor and diplomat George Kennan’s notion of “containment” in relation to Soviet communism became a kind of metaphor for postwar culture as a whole. Conservative forces in American government, corporate culture, and religion sought to restrict access to impulses that would shock or produce discontent in American women and adolescents, as well as racial and sexual minorities. The whole culture sought containment from threats ranging from nuclear fallout to deadly microbes to, in popular folklore and popular culture, alien invasions.

8

This did not mean that monsters disappeared from public life. Fascination with the gothic fears of freakery at the sideshow seems to have been displaced in postwar America by a fascination with the monstrous mutant in the movie theater. Atomic age fears of the dangers of radioactivity and nuclear fallout awakened the possibility of a silent, unbeatable horror—an odorless, tasteless, invisible death that could twist human bodies into horrible shapes.

9