Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting (32 page)

Read Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting Online

Authors: W. Scott Poole

A desire to see vigilante justice in the messy post-9/11 world only explains part of Dexter’s appeal for audiences. Like Patrick Bateman, he is a very American psycho and a much more appealing one. When we first meet Dexter, he is successful in his work and lives in a small but stylish apartment that is the perfect domestic nest for the metrosexual male, outfitted with the latest technology and IKEA minimalism. The show’s creators also make it clear that he is no sex maniac. The first episode of season one forcefully underscores Dexter’s heterosexuality by introducing his beautiful girlfriend (Julie Benz), a sweet single mom with perfect children who lives in a comfortable suburban home.

67

Dexter is the un-Norman Bates in numerous ways. He does not choose his victims in a psychosexual frenzy but rather on the basis of the Code. His issues are primarily paternal rather than maternal, an effort to come to terms with the demands, strictures, and, ultimately,

the limitation of patriarchal authority. His fondness for his girlfriend and her children doesn’t humanize him so much as it Americanizes him, giving him a traditional family unit that makes his other, secret life seem both comprehensible and compartmentalized.

Dexter taps more into America’s dreams than its nightmares. Like numerous characters in successful franchises since the late 1990s, Dexter attempts to live a prosperous, fulfilled, materially rich family life grounded in dark, nighttime activities that, in some sense, make that life possible. Not unlike HBO’s

The Sopranos

, AMC’s

Breaking Bad

, or Showtime’s other hit

Weeds

,

Dexter

critiques white, middle-class dreams while affirming them. Dexter’s appeal is that he departs in one significant way from the prosperous, successful mainstream and yet he still desires to be a part of it, to live a life where his boat, his family, and by season four, his suburban home, form a web of personal fulfillment. He is the perfect suburban warrior, meting out justice from the minivan he acquires in season three.

While signaling audiences with a recognizable mythology of the serial murderer, Dexter’s writers also revise and question that mythology. Did Harry recognize something inherent or, more likely, did he create something through investing Dexter with his bloody and unforgiving code? Dexter may be a monster but he is a Frankenstein’s monster, cobbled together out of his stepfather/creator’s own darkness. Perhaps monsters are made in our society more purposefully than we realize. In fact, perhaps our own beliefs about monsters and their intractable nature help to produce the monsters we fear the most.

68

By the fourth season of the show, which aired in the fall of 2009, the cracks are showing in Dexter’s persona and in the audience’s sympathy for him. At the time of this analysis, the show’s writers have radically called into question Dexter’s suburban lifestyle in an especially dramatic fashion, simultaneously suggesting that the murderer as celebrity is so deeply problematic that a miniature apocalypse is the result of our cultural romance with the murdering maniac.

Dexter

forces its audience to have the experience of realizing that they are fully and completely sympathizing with the sum of all fears;

a being who kills with no remorse and whose all-consuming self-regard allows him to decide who is innocent and who must be executed. Dexter implicates us in the crimes of a murderer. At a time when the President of the United States could refer to himself as “the decider” in matters of war and peace, Dexter used his code to decide who gets to live and who gets to die. The audience’s total identification with Dexter asks how much we are all humming along to the executioner’s song.

69

The fascination with

the serial killer sat at a very complex nexus of cultural nerve endings in late twentieth-century America. This newest American monster truly became a meaning machine that glossed attitudes toward sexuality, crime, mental illness, and celebrity culture. The excitement of the narrative grew from the clear lines it drew between good and evil and the lurid shock value of the most gruesome of the serial murderer’s escapades. Moreover, these monsters might be part of your everyday experience. Media interviews with neighbors and acquaintances of accused killers invariably told the same tale. He was “quiet and shy.” He was perhaps a loner but “seemed normal.” The monster was within, the stranger was beside us, and the call was coming from inside the house.

Maniac murderers as a growth industry in popular culture blurred the line between fiction and reality, changing with the transformation of American society over a forty-year period. A clear line of development can be seen between Leatherface and Dexter, one that mirrors social and economic changes in American society. The meaning of the maniac killer changed dramatically from the proletarian murders in Texas, Crystal Lake, and on Elm Street, to the sophisticated killers of Wall Street and South Beach. The American monster had come to the suburbs, not as an invader like Michael Myers, but as a permanent fixture. Along the way he became a fully Americanized psycho, willing to go a bit further to get the penthouse or the McMansion, but sharing the same values as the white middle class and those who imitated it.

The origin of the monster did not change over this long period of development. Norman Bates, Leatherface, Jason Voorhees, and Dexter all share a common tale of family dysfunction. In this way, the serial killer as monster spoke to the social upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s. These narratives found their greatest resonance at a time when the nature of the American family became a battleground, when family values became a rallying cry, and gender and sexuality became the center of political rhetoric. If Americans in the 1960s and early 1970s worried about the last house on the left, they soon worried that monsters might be living in the bedroom at the top of the stairs.

needs a priest … Jesus Christ won’t somebody help me!

—The Exorcist

—

Stephen King,

Salem’s Lot

I

n late December 1973 film patrons lined up around the block in every American city to watch some of the most terrifying images ever put on film. Using a documentarian style that created both a sense of

cinema verite

and of claustrophobia, director William Friedkin’s

The Exorcist

dragged America, literally kicking and screaming, into the bedroom of a teenage girl and forced them to face the devil.

The Exorcist

invites us into a bright, well-lit, Georgetown townhouse, the home of movie star Chris McNeil (Ellen Burstyn) and her daughter Regan (Linda Blair). Chris is starring in a film being made at Georgetown University about campus protest and the Vietnam War (that she laughingly describes as “the Walt Disney version of the Ho Chi Minh story”). The household is busy with the demands of McNeil’s career and social life while Regan, her adolescent daughter, seems well

adjusted in school, has an artistic bent, and wants a pony. All in all, this does not seem the setting of an American monster tale.

But strange things begin to happen to Regan. An Ouija board moves on its own. Regan’s bed shakes violently, and she uses foul language at the most inappropriate moments possible. At one point, she interrupts one of her mother’s fashionable dinner parties. Standing in her nightgown and voiding her bladder on the carpet, she pronounces doom on one of the guests, an astronaut who is about to begin an orbital mission. “You’re going to die up there,” she snarls.

McNeil goes first to the medical establishment, certain they will find some somatic explanation for her daughter’s behavior and the odd events that surround her. Neurosurgeons put the young girl through a battery of torturous examinations. Regan worsens and her upstairs bedroom becomes a chamber of horrors. She displays enormous strength, hurling a doctor across the room. Her skin has turned a garish green, covered with gashes and scar tissue, while her eyes have become feral and inhuman. In one harrowing scene, she masturbates with a crucifix.

1

Unable to find a medical solution, Regan’s physicians suggest to Chris that she find a priest to perform an exorcism, noting that “the power of suggestion” might help the young woman. McNeil revolts at the idea of finding a “witch doctor” but finally turns in desperation to Father Damien Karras, a young Jesuit with training in psychiatry. Karras receives permission from church authorities to conduct an exorcism with the help of an older priest, Father Merrin, who has experience with the ritual.

The ensuing struggle with the demon that possesses Regan administered a series of brutal and visceral shocks to audiences. The high production values of the film, unusual for a horror film in the early 1970s, made the makeup and special effects especially convincing. Perfectly paced, Friedkin’s film created massive unease, followed it up with shock, and moved to a climax of fear and, for some, the feeling that the ending had left the devil in charge.

2

The Exorcist

released right after Christmas 1973. Horror author Stephen King remembered that a terrified America could not get enough and began “a two month exorcism jag.” At one New York theater in early January, patrons waited four hours to purchase tickets. Showings of the film became spectacles that reflected the action on the screen. First time viewers fainted, ran out of the theater, and vomited. Others reported weeks of sleepless nights. Catholic priests, and soon Protestant pastors, received requests for exorcisms from frightened moviegoers, convinced that they had become possessed. One ticket-buyer for an early showing of the film told an interviewer that he or she “just wanted to see what all the throwing up was about.”

3

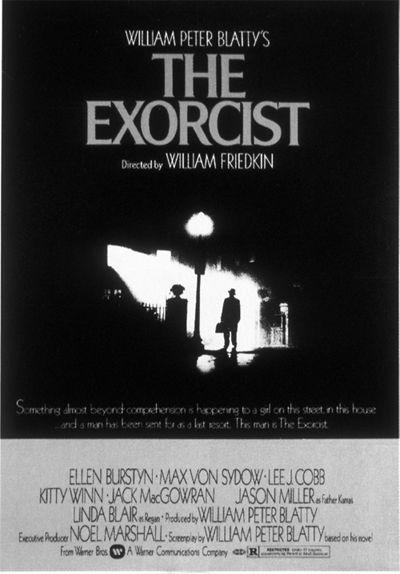

The Exorcist

Movie Poster

Friedkin’s brilliant direction and the film’s revolutionary manipulation of cinematography and special effects accounted for some of the extreme audience reaction. Perhaps even more significant than these factors,

The Exorcist

touched on both the transformation of the American family and the place of religion in American society. Linking family breakdown to supernatural terror proved a powerful concoction in 1973–1974 at a time when both family and religious faith became an arena of profound cultural contest.

Families and kinship networks have, for more than five millennia, served as a central organizing principle in human societies. Powerful patriarchal forces in traditional civilizations, including government, religion, medicine, and education, have viewed the family as the first line of defense for male privilege. The combination of intimacy and authority that exists within the household provides the opportunity to inculcate societal conceptions of gender, sexuality, and morality, as well as to examine and police behaviors deemed abnormal or dangerous.

4

Struggles for the liberation of women and sexual minorities in the 1960s raised numerous questions about the nature of family life in America. Second-wave fem

inism called for a radical redefinition of family life. A powerful and energized conservative response emerged by the late 1970s. Spearheaded primarily by religious leaders, the conservative movement fought back against what it perceived as an “attack on the family.” Unwilling to accept the transformative changes that rocked American society, conservatives mounted a highly successful sexual counterrevolution in the 1980s.

5

Underlying this titanic cultural struggle, anxieties over the body and its processes presented America with a new set of monsters. As the most intimate aspects of Americans’ biological experience became battlegrounds of the culture war, monstrous images came crawling out of the womb. Fear that the patriarchal family had risen from its grave to wreak terror, or the anxiety that rapid changes to the family would twist and corrupt America, became the basis of both horror films and popular urban legends. The human body itself, especially the female body, came to be seen as a monster or at least a monster-birthing machine.

6

Women’s bodies became the literal source of horror during the beginning of the culture wars.

The Exorcist

used the emerging sexuality of a teenage girl as a metaphor for diabolical evil. Brian De Palma’s film version of the Stephen King novel

Carrie

did something very similar. At the onset of menarche and with a growing interest in boys, Carrie becomes a conduit for powerful forces that lead to a blood-drenched dénouement. Women’s sexuality and reproductive abilities became the focus of numerous horror films throughout the 1970s, exposing America’s nervousness over contraception, abortion, the sexual revolution, and the changing nature of the family.

7