Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting (33 page)

Read Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting Online

Authors: W. Scott Poole

Sexually powerful women proved especially frightening to family values advocates as the sexual revolution came to full fruition in the 1970s. Freedom to experiment with sex and to imagine a life with more than one sexual partner became, especially for women, an extension of the politics of liberation born in the ’60s. Ready availability of effective forms of birth control as well as wide dissemination of knowledge about sex dimmed the possibility that sexual pleasure could lead to terrible consequences.

8

Given the intimate nature of the subject, statistical formulations of just how sexualized American life became during the 1970s are impossible to offer. Interviews done by sex researchers with a disparate sampling of American women do suggest that sexual experimentation, and improved sexual experience, became more common than ever before.

One housewife in her mid-thirties described to interviewers how “a bunch of us girls on the same block started reading books and passing them around—everything from how-to-do-it sex books to real porno paperbacks.” She noted that while some of the men complained about the “garbage” their wives were reading, her own husband “was always ready to try out everything.” Even the willingness to talk about sex to interviewers proved that once seemingly invincible social barriers had collapsed.

9

The willingness, even eagerness, of women to talk about their own sexuality registered the gains of the women’s liberation movement in life’s most intimate arena. Sexual guides like

The Hite Report

and

My Secret Garden

celebrated a woman’s sexual pleasure and the uniqueness of her sexual experience. Many women in the 1970s began to describe both giving and receiving orgasms as a celebration of personal agency and autonomy. One woman described how oral sex gave her “sort of the Amazon mentality—all powerful woman.” Another said that giving her partner fellatio meant that she was “exerting power” and that “the giving of pleasure is a powerful position.”

10

New technological innovations contributed to the new relationship American women had to their sexuality and their sexual partners. The introduction of Enovid-10 in 1960, better known as “the pill,” provided a safe and highly effective means of preventing conception. Mary Calderone, a feminist on the frontlines of the growing sex education movement, saw the pill effecting a decisive separation between sexual pleasure and pregnancy. By the 1970s, for the first time not only in American history but also in human history, a combination of scientific progress and dramatic social change made it possible to decouple sex and reproduction entirely.

11

The emerging New Right coalition wanted the party to stop. Conservative rhetoric in the 1970s and 1980s focused on the dangers of the sexually empowered woman who acted on her own agency. The new monster was a female monster, supernaturally productive of a brood of monstrous offspring. Conservatives feared that the family home had become a haunted mansion of female desire run amok, of monstrous reproduction free of patriarchal constraints. The untethering of reproduction from sexual experience transformed the American mother into an American monster.

Conservative critics of feminism explicitly portrayed sexually liberated women as unnatural monsters. Notably, they often conjoined sexual power and the ability to reproduce as an especially fearful mixture. Toni Grant, in a mix of pop psychology and conservative politics entitled

Being a Woman

(1988),

warned that men had become only “a means of procreation” that would be used by breeding women and then “discarded in black widow spider fashion.” Grant luridly described the independent woman as a “devouring, consuming monster” and suggested that the growing divorce rate meant that men were fleeing for their lives from these omnivorous

vagina dentatas

.

12

Monstrous women threatened, according to conservatives, to destroy the American economy as well as the American home. Conservative commenter Allan Carlson described the dangers of the “displacement of the patriarchal family by the matriarchal state.” Author and Republican activist George Gilder’s 1986 attack on feminism, entitled

Men and Marriage

(originally entitled

Sexual Suicide

), argued that women had become “masculine” even as men had become emasculated. This monstrous gender-bending would have consequences in the marketplace as well as the bedroom. Men, faced with the devouring female, would “lose their procreative energy and faith in themselves and their prospects.” Markets, Gilder asserted, would go into decline as America’s economic energy became focused on “welfare programs and police efforts required by a culture in chaos.”

13

The Reagan years saw both a rapidly growing inequality of wealth and the slashing of social programs that provided a safety net for the poor. Ironically, the “welfare queen” became a common trope used by conservatives who wanted to move from a critique of feminism to a warning about the dangers of the maternal state. While James Wilson warned of the “feral, pre-social” state of “the ghetto,” other conservative critics suggested that monstrous African American women, breeding huge numbers of fatherless, violent creatures, represented an apocalyptic danger. Gilder warned that “the worst parts of the ghetto” featured “a rather typical pattern of female dominance.” As scholar, fiction writer, and filmmaker Joshua Bellin points out, conservative writers imagined the typical African American woman as “a spectacularly fertile teenage incubator,” a monstrous womb that poured forth crime, poverty, and addiction as well as an army of angry African American men.

14

A number of horror films in the 1970s and 1980s mirrored, usually unwittingly, conservative critiques of women’s liberation and transformed rhetorical monsters into literal ones. David Cronenberg, the Canadian auteur of a number of disturbing body horror films, created a powerful nightmare of anxiety over female reproductive power in his 1979

The Brood

. Nola Carveth’s husband has her committed to an institution that employs a new method of psychiatry in which patients give literal form to their anger through cellular changes in the body. Carveth’s

feminine rage becomes a dark energy fueling an asexual conception and producing dwarf mutant children who begin killing and maiming all they come in contact with. In one especially unsightly scene, Nola, the monstrous mother, is portrayed animalistically licking blood and effluvium off of one of her recently produced egg sacs.

Nola’s husband is portrayed as the sympathetic figure in contrast to his monstrous wife. Even before Nola begins breeding little monsters, she is presented to us as callous, foulmouthed, and generally unpleasant. Her psychological problems are rendered as both severe and unsympathetic. Cronenberg suggests that she is suffering from the ennui of the liberated woman who has it all and yet still cannot find a way to be happy and mentally stable. Her search for personal growth shows her to be such an angry feminist that she produces monsters that destroy her family.

15

Notably, Cronenberg has described the film in highly personal terms, explaining that it emerged out of anger over his divorce and the subsequent child custody battle. He has also described the scene of Samantha licking the membrane as no more disturbing than “a bitch licking her pups.” Horror historian David Skal has suggested that Cronenberg considered his subject “to be a bitch on any number of levels” and quotes a contemporary

London Observer

review that concluded the film “has something pretty terrible to tell us … about the fears of North American males.”

16

In the same year that Samantha’s brood wreaked havoc, another monstrous mother attempted to reproduce herself, and slaughter anyone who got in her way, aboard the spaceship

Nostromo

. Ridley Scott’s

Alien

combined science fiction with the sensibilities of gothic horror to give the ’70s its most iconic monstrous mother.

Alien

, with set designs by the Swiss surrealist artist H. R. Giger, offered a complex message about women, the body, and reproduction. The monster itself is a mechanical-looking, fanged, insect-like, and specifically female messenger of death, referred to as “the Bitch” several times in the

Alien

series (“The bitch is back” became the catchphrase advertising the sequel). The alien she-beast uses the

Nostromo

as a nest to breed her young, transforming her human victims into incubators for her spawn. In the film’s most notorious scene, a fetal alien explodes out of a male crewmember’s chest. The power of the

Alien

to reproduce on its own outrages the male body, literally tearing it to pieces.

The Alien’s savaging of the

Nostromo’s

crew could easily be read as a reactionary message that toyed with male anxieties over women’s increasing control over their bodies and reproduction. This image is

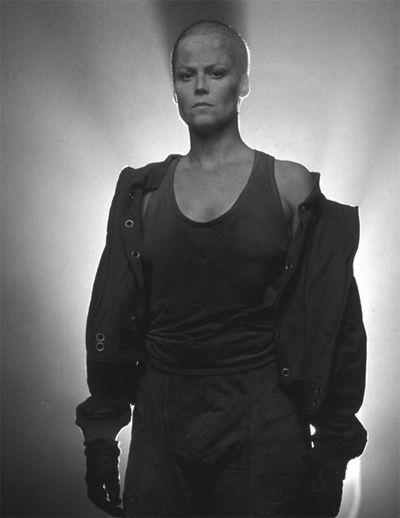

balanced, however, by Lieutenant Ripley, Sigourney Weaver’s character who fused the typical action hero with the slasher genre’s “final girl,” the one who uses courage and ingenuity to survive the night. Moreover, as the classic

Alien

sequels show, Ripley becomes a kind of mother who, in the film’s final installment, asserts her own ability to control her biological destiny by destroying the alien spawn growing within her. In this final sequel, Ripley has shaved her head and become a “bitch” in the politically conscious sense of the term, refusing to allow biology to be her destiny. Notably

Alien 3

appeared in 1992 after a series of Supreme Court rulings that allowed states to place barriers between women and abortion, including parental consent for minors and strictures against family planning clinics counseling abortion as an option.

17

Alien 3

by David Fincher

Numerous films in the 1970s joined

Alien

in playing with the frightening potentialities of female biology and the politics of reproduction.

It’s Alive

(1974), with its tale of a clawed, mutant horror that comes out of its mother’s womb as a killing machine, appeared one year after the

Roe v. Wade

decision.

It’s Alive

directly addressed the politics of sexuality and reproduction. We learn that the couple, the Davies, considered an abortion early in pregnancy since, the husband tells a police detective, “everyone inquires about it these days … but we decided to have the baby.” “

Everybody makes mistakes,” the detective responds, aware that the couple has created a monster.

The increased role that technology played in human reproduction haunts

It’s Alive

. The title is, of course, a reference to Dr. Frankenstein’s infamous cry of triumph in the 1931 Universal film. Mad science run amok seems to be behind the horror. The origin of the mutation is never explained, though we learn that Lenore Davies had been taking birth control pills for thirty-one months prior to her pregnancy. A doctor working for a major corporation recommends “absolute destruction” of the monster child to prevent any discovery of malfeasance on the part of the pharmaceutical industry or laxness on the part of the FDA. At one point, Frank Davies calls the child a “Frankenstein” and ruminates on how he always thought that Frankenstein was the name of the monster when he was a kid but, when he read the novel in high school, he learned that it was the name of the monster’s creator. “Somehow,” he says, “the identities got all mixed up.” “Best not to take escapist literature too seriously,” responds a scientist who wants to use the monster’s body for research.

It’s Alive

, and all of the 1970s films of fetal terror, owe something to the 1968 Roman Polanski film

Rosemary’s Baby

. Polanski had already explored how the sexual counterrevolution could become a horror film; his movie

Repulsion

tells of a repressed young girl’s descent into psychosis and murder.

Rosemary’s Baby

gave him the opportunity to probe the emerging clash between second-wave feminism and religious conservatism.

Rosemary’s Baby

tells the story of Guy and Rosemary, a young couple given the chance to move into a Gilded Age apartment building known as the Bramford (actually filmed at New York’s famous Dakota building). The film opens like a Doris Day-lite picture with the attractive young couple beginning their life together in a well-appointed apartment and getting to know their wacky, elderly neighbors. Soon enough, the monster begins to appear. Rosemary has disturbing dreams of being raped by a demon. Guy, a struggling actor, gets a part in a play but only after his rival is mysteriously killed in an accident.

When Rosemary discovers that she is pregnant, she finds herself the center of the apartment building’s attention. The film encourages the audience to share her mounting sense of paranoia as everyone from her doctor to her neighbor attempts to sequester and control her, feeding her a disgusting, meaty mixture and constantly monitoring her body and behavior. The film becomes increasingly surreal as Rosemary discovers that her quirky neighbors are, in reality, a satanic coven, and her husband has made a Faustian pact, giving her body and her womb to

Satan in return for a career boost. She gives birth, against her will, to a child that has “his father’s eyes,” the eyes of the devil.