Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting (37 page)

Read Monsters in America: Our Historical Obsession with the Hideous and the Haunting Online

Authors: W. Scott Poole

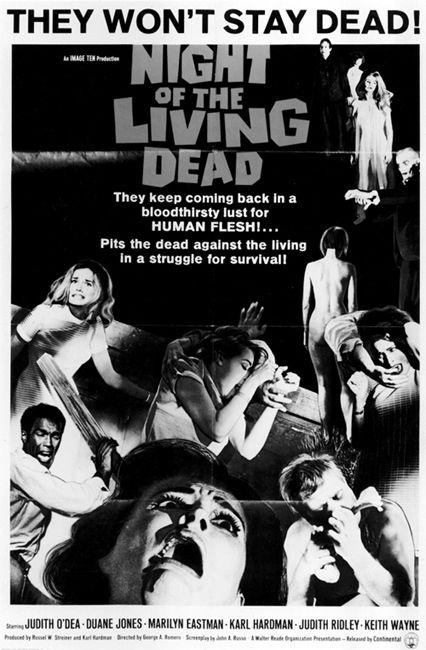

They were coming to get Barbara, and everyone else. The shambling figure turns out to be a zombie who kills Johnny as Barbara escapes to a nearby farmhouse and becomes catatonic with terror. A young African American man named Ben also occupies the farmhouse as does, we learn soon, a family that has been hiding in the basement. The group, fighting among themselves, also must fight a horde of hungry zombies who surround the small house. Ben learns from a radio he has discovered that “those things”

are a global phenomenon, a zombie apocalypse. Humanity has been besieged by hordes of cannibalistic, animated corpses.

Dracula from Hammer

Shot for a little over one hundred thousand dollars in rural Pennsylvania, Romero’s film was filled with local actors and friends from his native Pittsburgh. Filmed in black and white (for financial as well as aesthetic reasons),

Night of the Living Dead

became a staple of drive-in theaters around the country, and created, to date, five sequels and numerous remakes, tributes, and reimaginings.

1

Night of the Living Dead

shaped the modern zombie genre, a new monster for the dark American pantheon. Zombies had played some role in African American folklore in the coastal South and appeared in Universal’s tellingly titled

White Zombie

and RKO’s

I Walked with a Zombie

. Both films borrowed the zombie figure from the religious traditions of the African Atlantic and its folklore about an evil

papaloa

(shaman able to channel spirits) that had the power to transform corpses into undead servants. Romero’s hordes of zombies broke with this tradition. He and his imitators imagined undead humans in various states of decay, driven by their hunger rather than by a necromancer’s will. The rising dead, in this new version, could create more zombies, passing on their infection through a bite. The whole human race could be transformed into monsters.

2

Zombies retained their popularity in American culture through the 1970s and 1980s in Romero’s follow-up films

Dawn of the Dead

and

Day of the Dead

.

Their popularity spiked in the early part of the new century. During the same period, American pop culture witnessed the ascendancy of a monster that, in some respects, never went fully out of style. A new version of the American vampire rose from its coffin in the ’70s, and followed a similar trajectory of celebrity as the zombie, his more proletarian monster cousin.

3

Night of the Living Dead

Poster

Like the zombie, the vampire had appeared in slightly different incarnations earlier in the twentieth century. Lugosi’s Dracula, a monster sophisticated enough to stalk his victims at the opera, had enormous popularity on his first appearance but soon found himself eclipsed by Boris Karloff’s

Frankenstein

and the barrage of mad scientist movies that followed. In 1958 American audiences thrilled to Christopher Lee’s new interpretation of the vampire in the British Hammer Studios’

Horror of Dracula

. Lee’s version of the Count kept the sexual allure of Lugosi’s vampire king while adding an animalistic cruelty, and hungry, bloodshot eyes that transformed the Count into a bloodthirsty sensual Miltonic Satan.

4

Alluring and yet monstrous, the Lugosi–Lee vampire tradition would be replaced by Anne Rice’s Louis and Lestat in

Interview with the Vampire

.

Rice’s 1976 novel

framed its story around a young reporter listening to Louis relate his more than a century as one of the undead, a story that introduced the reader to a larger community of vampires and a secret vampiric history of the world. Rice told this tale of hunger and eternal life as one rich with pathos, passion, and exquisite suffering (so much so that at the end of the novel the reporter, who clearly stands in for the reader, begs to be made one of the undead). Rice followed up the best-selling

Interview

with a cycle of vampire tales centered on Lestat who, like Louis, is a tortured, glamorous, undead soul. The sexy sadistic monster had become the sexy sympathetic monster.

5

The mythologies and cultural meanings of these two creatures, zombies and vampires, are very distinct. At the same time, they have certain similarities that have led to their current joint reign as the undead monarchs of American popular culture. Both the zombie and the vampire draw on themes embedded in the history and theology of American Christianity and its struggles in the late twentieth century. Both are, in fact, heavily redacted versions of the American Christian millennialism’s hopes for immortality. They each articulate meanings theologically important to Americans since the Puritan era and are the walking, flying, roaming, and shambling embodiments of the “resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come.”

6

The vampire and the zombie are monstrous keys to American experience over the last three decades. These creatures, flesh eating or blood drinking, decomposing or forever young, appeared as pop culture phenomena at a historical moment when the body had become of central concern in American culture as the vehicle of pleasure, of theological meaning, or of personal happiness (or all three at once). Anxiety over threats to the body became a paramount concern as evidenced by the popularity of dieting and exercise regimens, public health campaigns, and the growing acceptance of plastic surgery as an aesthetic renovation of the aging or unsightly physical self.

7

Vampires and zombies are further linked with one another in their origins and popular mythologies. Unlike almost every other creature examined in this book, the vampire and the zombie as currently imagined have no analogue in American folklore and/or urban legend. These voracious living corpses are almost pure creations of American popular culture, their titles and motifs lifted from European and Caribbean legend and transformed into horrific celebrities. Perhaps more than any other monster, they are “made in America” as commodities for sale and distribution. This makes them important representations of what

Americans fear, or desire, from the monster at the beginning of a new millennium.

8

The vampire and zombie are, like all monsters, shaped by their historical context. Historical events of the last third of the twentieth century helped prepare the way for the resurrection of the undead in movies and television. The legacy of the Vietnam War in particular became a silent partner in the birth of modern horror. Many conservatives saw the war as creating what Ronald Reagan later called the “Vietnam syndrome,” a profound loss of national confidence. Backlash against feminism would be motivated by the sense, sometimes inarticulate but always present, that American women and other minorities had gained political consciousness in the ’60s and ’70s while white men had lost a war. Returning veterans came home to a world where the ground had fundamentally shifted. For Americans who had watched the war from their living rooms and mourned the deaths of their children, parents, and spouses at tens of thousands of funerals, the war itself became a kind of undead monster, one that overcame every attempt to keep it in the ground.

9

Body Bags

The entrance of the United States into a postcolonial conflict in Southeast Asia became a multidecade commitment that killed 58,000 Americans and wounded 153,303 more. An incalculable number of Vietnamese died in the conflict as well, victims of carpet bombing and chemical warfare.

10

This massive loss of life was born of the frustrated efforts of an imperial power trying to squelch an armed peasant revolution. General William Westmoreland, commander of American forces in Vietnam between 1964 and 1968, implemented a strategy of “attrition,” or the killing of as many Vietnamese as possible in order to break the peasant revolution’s will to fight. The idea of attrition made the creation of a Vietnamese “body count” central to war-winning strategy. This attitude filtered down through the ranks to exert pressure on every officer that commanded a platoon. Former Marine Lieutenant Phillip Caputo remembered that “the pressure on unit commanders to produce enemy corpses was intense.” Platoon members took souvenirs of ears, noses, and even scalps to impress their commanders and substantiate claims of a high body count. Some platoons actually padded their kill ratio (“box scores” some called it) by counting small blood traces and at least some unit commanders demanded severed body parts as clear testimony that their troops had performed their duty.

11

Bureaucratic pressure to produce Westmoreland’s desired rate of attrition degenerated into careless brutality. The infamous My Lai massacre represents the most egregious case of the everyday horrors American forces visited on their hidden enemy, the incident with the highest box score. On May 16, 1968, a company of U.S. soldiers entered the small village of My Lai, rounded up the inhabitants (mostly women and children), placed them in a ditch, and turned murderous gunfire on them. Army investigators later placed the death toll at between four hundred and fifty and five hundred people, some of them infants in their mother’s arms.

12

Wanton cruelty became the everyday result of American policy. One marine described the “fun game” of tossing candy out of the back of a transport truck, leading Vietnamese children to run for it and possibly be mangled by the next truck in line. A Vietnamese peasant woman remembered how passing soldiers in a truck grabbed her son’s hat and pulled him (it was held to his head with string) under the vehicle’s tire, killing him. These random acts by some individual soldiers are dwarfed by the death and destruction wrought on the Vietnamese people by the indiscriminate use of artillery and airpower.

13

The horrors American military personnel visited on the Vietnamese were replicated in the horrors they themselves endured, both in terms of bodily wounds and psychological damage. To the fifty-eight thousand American dead would be added seventy-five thousand physically disabled veterans. The trauma of the war left tens of thousands more with nightmares, severe depression, and other psychological maladies. In at least one case analyzed by anthropologist Mai Lan Gustafsson, a veteran came to believe he was haunted by the angry spirit of a Viet Cong fighter whose ID tag he had taken in 1968. The vet only found peace when he returned to Vietnam and gave the tag to the fighter’s mother.

14

American journalism made Vietnam the first truly televised war, and magazines such as

Time

and

Life

created a massive photographic record of wounded, dead, and dying Americans. Vietnam came to be known as “the Living Room War” with images of troops returning in body bags becoming an indelible image of the failure of American policy in Southeast Asia. Dismemberment entered the public record and became part of popular culture.

15

Romero’s zombies shambled on-screen as Americans became increasingly used to real-life images of graphic death, gore, and body parts blown to pieces. In January of 1968 the Tet Offensive inaugurated a new period in the Vietnam conflict and initiated house-to-house and hand-to-hand fighting. American causalities soared throughout the year

with one week in February of 1968 bringing news of five hundred thirty-four American deaths. Romero’s images of rotting corpses on a violent landscape covered with entrails and viscera, and a band of survivors battling it out with faceless hordes and deeply divided among themselves, perfectly suited the American mood.

In the years ahead, Tom Savini would do an even better job of bringing these rotted corpses to life. Savini had been friends with George Romero during their youth in Pittsburgh and would likely have worked with him on

Night of the Living Dead

had he not been called up to serve in the army the same year. Savini carried a makeup kit with him through basic training and even used collodion, a liquid plastic, to make up a drill sergeant who wanted to frighten his next platoon. Sent to Vietnam as a combat photographer, Savini brought home a blend of trauma and creativity that led him to become the greatest makeup effects artist since Lon Chaney Sr.

16