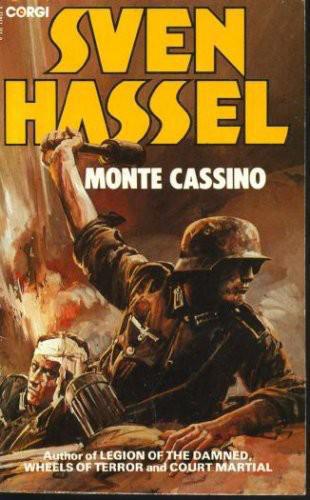

Monte Cassino

Monte Cassino

By SVEN HASSEL

God! how it rained! It poured and poured. Everything was sopping. Our mucky rain-capes were long since wet through.

We were sitting under some trees in a sort of tent made by buttoning capes together. They were SS capes and better than ours and we were relatively dry. Tiny had also put up his umbrella.

We had finally got the stove from the big house burning and we were getting ready to dine. We had forty starlings which we were roasting on long sticks, and Porta was making marrow-balls. It had taken us two hours to scrape that marrow out of the bones of two dead oxen. We had found some fresh parsley. Gregor Martin knew how to make tomato ketchup, which he was mixing in an American steel helmet. Steel helmets were practical things, capable of being used for lots of purposes. The only thing they were useless for, was the purpose for which they were made.

Suddenly, we burst out laughing. It was Tiny's fault. He had made a classic remark without realising that it was classic.

Then Porta held up his yellow top hat and announced that we were to inherit it, when he died. And we bellowed at that.

Then by mistake Heide pissed into the wind, and we rolled about with laughter, and we were still laughing as we ran back with our food between the bursting shells.

Once I heard a padre say to one of the staff officers:

"How can they laugh like that?"

That was the day we were laughing over Luisa Fatarse's knickers which Tiny was wearing tied round his neck, and I swallowed a piece of potato the wrong way and had to have my back pummelled with a hand grenade. Laughter can be pretty dangerous.

"If they didn't laugh as they do," the staff officer replied, "they would not be able to carry on."

Porta had a masterly hand with marrow-balls. He made only ten at a time, otherwise they went soggy, eating his own share in between. We ate over 600 between the nine of us, which is quite a lot, but then we were all night at it.

God, how it rained!

The thunder of the guns could be heard in Rome, 170 miles away. We could not see the great men-of-war out at sea, but every time they fired a broadside, it was like volcanoes erupting on the horizon. First there was a dazzling flash of fire, then a thunderous roar.

They knocked our grenadiers cold. In the course of a few hours our weak panzer regiments were rolled up. From Palinuro to Torre del Greco the coast was a flaming furnace, whole villages were wiped out in a matter of seconds; one bunker a bit to the north of Sorrento, one of our biggest that weighed several hundred tons, was sent flying high into the air along with the entire crew of its coastal battery. Then out of the south and west came swarms of low-flying Jabos* that shaved the roads and paths clean of all that lived. One hundred miles of Highway 19 disappeared altogether, and the town of Agropoli was razed to the ground in twenty seconds.

*Fighter-bombers.

Our tanks, devilishly well camouflaged, were standing in readiness among the cliffs. The grenadiers of the 16's were with us, lying under cover of the heavy brutes. We were to be the great surprise when they did come, those men from across the sea.

Thousands of bursting shells churned up the ground and transformed a hot sunny day into dark night.

An infantryman came running up the slope without his rifle, arms flailing, crazed with fear, but the sight made no impression on us. He was one of many. That morning I myself had been in the grip of the paralysing fear that strikes one rigid. It could come over you as you were marching along, turning you into a corpse, except that

you were still on your feet. The blood drained from your face, making it deathly white, and your eyes stared: As soon as the others noticed what had happened, they began pummelling you with their fists. If that was not enough, they used their feet and rifle-butts, and when you collapsed sobbing, they just kept hitting away. It was brutal treatment, but it nearly always worked. My face was badly swollen after the treatment Porta had meted out to me, but I was grateful. If he had not been so thorough, I would probably have been on my way to the rear in a strait-jacket.

I looked across at the Old Man lying between the tracks of his tank. He smiled and nodded encouragingly.

Porta, Tiny and Heide were throwing dice, using a piece of green baize that Porta had "organised" in Palid Ida's whorehouse.

A company of infantry on its way down the mountainside ran right into a salvo from the ship's guns. It was as if a giant hand had just brushed them away. There was not a thing left of 175 men and their hill-ponies. The Jabos came when the sun was low in the West and right in our eyes. Swarms of landing craft spewed infantry over the beach: old tanned veterans, professional soldiers and young anxious recruits called-up only a few months before. It was a good thing their mothers couldn't see them. Dante's hell was an amusement park compared to what they had to go through.

Our coastal batteries had been knocked out, but behind every stone and in every shell hole lay grenadiers, mountain troops, paratroops, with their automatic weapons, waiting. Light and heavy machine guns, trench-mortars, panzerfausts, flamethrowers, automatic cannon, assault carbines, rocket-projectors, machine pistols, rockets, hand grenades, rifle grenades, mines, Molotov cocktails, petrol bombs, phosphorus shells. So many words, but what terrors they harboured for an advancing infantryman!

Under cover of their ship's guns they shot ropes up the cliffs and clambered like monkeys up the swinging ladders or went tumbling down from the jutting top. Flocks of them ran in circles about the white sand, while

our phosphorus consumed them. The beach was a sea of flame, that turned the sand into lava.

We were silent spectators. Our orders were "no firing."

The first wave was destroyed. They did not get even 200 yards up the beach. A grim sight for the men of the second wave when it followed. They too were shrivelled up. But fresh hordes kept pouring ashore. A third wave. With guns raised well above their heads, they ran through the roaring surf, flung themselves down on the beach and hammered away with their automatic weapons. And they did not make even a yard's progress.

Then the Jabos came, bringing phosphorus and naphtha; yellowy-white flames shot up towering into the sky. The sun went down, the stars came out and the Mediterranean played lazily with the charred bodies, cradling them gently at the water's edge. The fourth wave of infantry landed. Star shells rose into the sky. These men also died.

Just after sunrise, an armada of assault craft roared towards land. These were the professionals, the Marines who were to have established themselves, once the others had opened the way. Now they were going to have to do both, open the way and establish themselves. Their main task was to deprive the enemy of Highway 18. Their armoured cars remained at the water's edge like so many burning torches, but, tough and ruthless, the veterans made their way forward. These men from the Pacific killed everything that crossed their path, shot at every corpse. They had short glinting bayonets on their assault carbines, and many of them had Japanese Samurai swords flapping against their legs.

"US Marines," Heide growled. "Our grenadiers will get it now. Those lads haven't lost a battle in 150 years. Each one of them is worth a whole company. Major Mike'll be glad to see his old chums from Texas."

It was our first encounter with the Marines. They seemed to have tricked themselves out in whatever they liked: one went storming up the beach with a bright red open parasol fastened to his pack, followed by a huge sergeant wearing a Chinese bast hat on top of his helmet.

At the head of one company ran a little officer with a Maurice Chevalier straw hat on the side of his head, a rose beckoning gaily from its light blue ribbon. They stormed forward quite regardless of the death-bringing fire from our grenadiers' automatic weapons.

One German infantryman tried to run, but a Samurai sword severed his head from his body. The American who had wielded it called something to his companions, waved the grim weapon above his head and kissed its bloody blade.

A swarm of Heinkel bombers dived down over them. The entire beach seemed to rise up towards the clear sunny skies and the soldier with the Samurai sword lay writhing in a pool of blood on the smoke-blackened sand.

Leutnant Frick came crawling up.

"Withdraw singly. We're pulling back to Point Y."

The Marines had got through our positions. Fresh landing craft were being run up the beach. Amphibian craft roared ashore while bombers and fighters fought savagely in the clear sky.

A group of grenadiers surrendered, but they did so in vain for they were mown down ruthlessly. Some of the Marines stopped to plunder the bodies of their medals and badges.

Porta grinned and said: "Collecting fanny-attractors."

"Bon!

Now we know the rules. Good thing we saw that," said the Legionnaire.

We fell back to a couple of kilometres south of Avelino, knowing that the German Command counted on being able to defeat the invading force, once it had got ashore. They were hoping for another battle of Cannae, but they had failed to take into account the Allies' enormous material superiority. Where Field Marshal Alexander and General Clark had only hoped for a bridge-head, they were presented with a proper front. Position after position was taken, but still we weren't sent in. We had very few casualties, but we were pulled back to north of Capua, stopping long enough in Benevento to drink ourselves silly in a wine cellar. After we had helped to bury several thousand dead at Caserta, the regiment dug itself in at the fork where Via Appia parts company with Via

Casilina. We dug our Panthers half in. We had a barrel of wine from Caserta stowed behind the engine hatch on ours; a spit-roasted pig hung from a pole over the turret. We lay on the forward hatch, throwing dice on Palid Ida's bit of green baize.

"How would you feel about plugging the old Pope and smashing the Vatican organisation?" Barcelona asked, in the middle of a good throw.

"We do what we're ordered to do," Porta replied laconically. "But why should we have to plug His Holiness? We haven't even fallen out with him."

"Yes, we have," Barcelona said, pluming himself with being in the know. "That time when I was One-Eye's orderly, I saw a RSHA* order on the NSFO's+ desk at Corps HQ and read it. The boys in Prinz Albrecht Strasse are very keen to get the Pope to come out openly on the side of the hook noses. They have

agents provocateurs

in the Vatican. As soon as the holy wallah has been induced to take sides, the whole lot are to be smoked out. Every crow is to be put to the sword. I can give you the end of this nice little document word for word:'On receipt of the code word "Dog-collar" a special duties Panzer regiment, demolition engineers and panzer-grenadiers from the SS Tagdkommando will go into action.' "

*Reichssicherheitshauptamt (Security HQ). +Nazi Welfare Officer (political).

"But, damn it, you can't shoot the Pope," Heide exclaimed, forgetting in his surprise that he had thrown a winner.

"They can, and a lot more," said Rudolph Kleber, our minstrel, who used to be with the SS. "Six months ago a friend of mine in the Bible Research Section told me that they were very anxious to get to work on the crows. They are laying trap after trap for the Holy Father. In Prinz Albrecht Strasse they regard him as Adolf's worst enemy."

"Bugger that," said Barcelona, "but would you plug the holy man, if you were ordered to?" We looked questioningly at each other. Barcelona had always been a stupid swine capable of asking the most idiotic things.

Tiny, our six foot illiterate from Hamburg and the most cynical killer of all time, held up his hand, like a child at school: "Listen here, you scholars, which of us is a Catholic? Nobody. Who here believes in God? Nobody."

"Attention, mon ami!"

The Legionnaire raised an admonitory hand.

But there was no stopping Tiny once he had got into top.

"My Desert-Roamer, I know you're a Mohammedan, and I say like Jesus, Saul's son," Tiny was getting his bible history a bit mixed up, "Give me what's mine, and slip a coin or two into the emperor's palm. What I would like to know is this: is this fellow Pius in Rome, whom you've been talking such a hell of a lot about, is he just a high priest in white, a sort of Church general, or is he deputy of the commander-in-chief in Heaven, as that nurse who gave me some ointment for my eye told me he was the other day?"

Porta shrugged. Heide looked away. He was playing with a couple of dice. Thoughtfully Barcelona lit a cigarette. I was changing the fuse in a rocket. The Old Man ran his hand across the breech of the long gun.

"I suppose he is," he muttered thoughtfully.

Tiny drummed on his teeth with the nails of his left hand. "Obviously none of you is quite sure. You're on uncertain ground. Obergefreiter Wolfgang Ewald Creutzfeldt is a tough lad and one dead man more or less does not matter a shit to him. I'll shoot anybody: private or general; whore or queen, but not the holy man."