Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (99 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

Figure 4.29

Karak, Baybars’ panther adorning the inscription on the southern keep

lower. The tower is preserved to its full height and a line of merlons pierced with arrow slits can still be seen crowning the top. Cisterns were built at the base, ensuring the water supply.

A band inscription ran along the top of the tower. The inscription on each side begins and ends with the sultan’s royal emblem – the panther (

Figure 4.29

). The inscription is partly eroded and certain sections can no longer be made out. The location at such a height is rather surprising; it could hardly have served for propaganda purposes since passers-by would scarcely have seen it, let alone paused to read it. The inscription mentions Baybars and two of his

nisbas

, and

and . The date at the end of the inscription is 673/1274–5.

. The date at the end of the inscription is 673/1274–5.

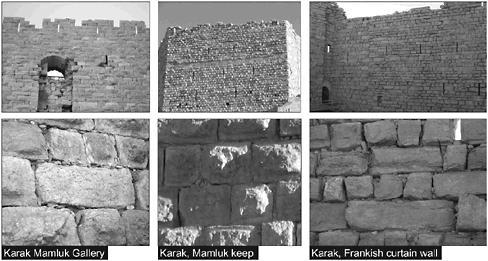

The western galleries and the keep are homogeneous in style, construction methods, the type and size of stone used (local soft limestone) and the style of masonry. It seems that the local masonry tradition was followed and although the quality of the Mamluk masonry at Karak is better than that of the Franks, compared to the Mamluk masonry at Safad and , Karak is by far inferior (

, Karak is by far inferior (

Figure 4.30

).

Figure 4.30

Karak, Mamluk and Frankish masonry

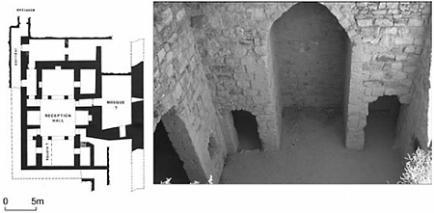

Figure 4.31

Karak, the western wall of the fourteenth-century Mamluk palace

One of the most important roles of the fortress was to provide a place of refuge for nobility and royalty. Young heirs whose existence in Cairo was threatened or threatening either fled to Karak or were banished to it. found refuge at the fortress twice (1298–9, 1308–10) before he acceded to the throne and established himself as sultan. According to written sources and the archaeological data the modest residential quarters were built by

found refuge at the fortress twice (1298–9, 1308–10) before he acceded to the throne and established himself as sultan. According to written sources and the archaeological data the modest residential quarters were built by in the early fourteenth century.

in the early fourteenth century.

A subterranean complex (25 × 22m) identified by Brown as a palace was uncovered in the southern part of the fortress. It has an elongated plan, dominated by a central open reception hall. There is an

īwān

on either side of the central hall and two large rooms branch of it. A small mosque was built to the east (

Figure 4.31

). In the interior one can still see the remains of fine masonry and plaster.

206

This plan had already been well established by the end of the Ayyubid and early Mamluk periods.

207

It is difficult to compare the Frankish construction to that of Baybars. Military architecture had advanced considerably since the days of Paganus who first built the fortress in 1142, and even the later Frankish phase dated to the 1160s does not match the Mamluk work at Karak. True to his principles, Baybars left the Frankish curtain walls along the east as they were. Although the Frankish work did not match the standards of thirteenth-century military architecture, other than the two towers that were destroyed, most of the Frankish fortress was left intact and maintained.

Before leaving, the sultan appointed a new

nā’ib

; the garrison was strengthened, salaries paid, storerooms stocked with arms, part of the sultan’s treasury brought to the fortress,

208

and the granaries inspected. Assuming that work began in 1263 after the fortress was taken, it took a decade to complete this building project. It seems there was no immediate threat and no one was in a great hurry to complete Karak’s fortifications.

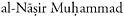

Fortresses along the Euphrates border

The main routes leading from Mesopotamia to the ports on the Mediterranean passed through the middle course of the upper Euphrates. The reason for preferring the road leading across the upper Euphrates is the considerably short distance from this section of the river to the coast (

Map 4.1

).

There are seven fords along the stretch of the river starting from Carchemish to the modern Ataturk dam (approximately 165 km). Some fords were still in use in the mid twentieth century.

209

Most of the river crossings were well established by the Hellenistic and Roman periods. The Roman organization of the Euphrates frontier partly correlates with that of the Mamluk–Īlkhānid frontier. Seleucus I founded the city of Zeugma (c. 300 BC) on a ford 15km north of the medieval fortress of al-Bīra, to safeguard the crossing.

210

During the early Roman period this became the main crossing point between Rome and Parthia, and in the middle of the first century ad the tenth legion was based in the town.

211

Parker suggests that “A large number of legions would have been required to hold even the vulnerable points on this line, and, doubtless from financial reasons as well as military and political inexpediency, Augustus decided against such a course and

Map 4.1

The middle course of the upper Euphrates

concentrated his army in Syria while making use of client kings … to act as buffer states between Rome and Parthia.”

212

This strategy did not endue and by the second century ad the Roman frontiers were reorganized. The font lines had fortresses protected by cohorts of auxiliaries. The legions ere stationed in large camps directly connected by roads to the frontier fortresses.

213

The Mamluks’ strategy closely resembles that of the Romans during the second century ad. It seems that since from the outset the sultans had a limited source of manpower they reached the same conclusion.

Al-Bīra became an important crossing point only when Zeugma declined, possibly in the early Middle Ages. The advantage of having a crossing at al-Bīra is directly related to the width of the river (180–200m). The wider the river the slower the current, which makes it easier both to cross and to maintain a pontoon bridge. An important point concerns the seasonable floods. Although building a bridge might have been feasible, a solid stone or brick bridges would not have survived the force of the flood. Thus from as early as the Seleucid period until the early twentieth century ferries and pontoon bridges, of various descriptions, were used for crossing.

214

The river crossing to which the site owed its importance is mentioned in a number of Muslim sources. Ibn al-Athīr refers to a bridge used by al-Dīn in 1179.

al-Dīn in 1179.

215

Bar Hebraeus notes the bridge tied across the Euphrates used by Hülegü’s forces in 1259. In the mid fifteenth century Ibn reports that a string of boats tied to one another served as a bridge

reports that a string of boats tied to one another served as a bridge .

.

216