My Father's Fortune (6 page)

Read My Father's Fortune Online

Authors: Michael Frayn

Then there are quiet afternoons at home, when it's too wet to go out in the garden and nothing's happening anywhere in the world; afternoons when we beg her to play the violin to us. She refuses. She has forgotten everything she ever knew, and in any case there are no strings left on the violin. Perhaps it's on one of these afternoons that she tells us about the ship of gold waiting in Chancery, to distract us from our pestering. We can't be distracted for ever, though. The gold seems a long way off; the violin's right

here, in a wooden case which is kept in the impenetrable tangle of dusty junk that has accumulated in the little cupboard under the stairs. We plead, we nag, we whine. We open the cupboard and threaten to look for the violin case ourselves.

And sometimes she gives in. Probably to save us from getting killed in the hellhole under the stairs, because extracting anything from those dark seams of junk is as difficult as coal-mining â and almost as dangerous, since you have to squeeze past the fuse boxes, and most of their china covers have long since cracked and vanished. When the case is opened at last it releases a scent of the past from the dusty blue velvet lining. It's as intoxicating as the atmosphere of a Southern Railway compartment. There, exactly fitting the blue cushions, is the violin. We gaze at it with awe. Its swelling shiny woodwork is blond, the colour of pale ale. The fingerboard and the tailpiece are a mysterious ebony, the swell of the belly and the curves of the scroll imperiously idiosyncratic. It's visibly fragile, visibly precious.

Our mother's right â the strings are all snapped and curled up on themselves. She searches through little pockets in the upholstery of the case where attachments and spares are kept, and finds an E and a D, then plunges back into the junk mine under the stairs. She brings out another violin case. In it is her father's violin â dark, like a Guinness beside my mother's, an object of veneration only in so far as it can be cannibalised to keep hers going. She searches through more pockets, takes strings off the instrument itself, somehow locates a G and an A.

We watch the familiar ritual spellbound. She uncleats one of the bows from the lid of her own case and twists the little polygonal metal knob in the handle, inset with mother-of-pearl, to tighten the horsehair. She bounces the bow against her forearm to test the tension, tightens again. She takes a little circular brown cake out of one of the pockets in the case and holds it in a cloth while she draws the bow over it. âRosin,' she explains. She draws the bow over the G string, and briefly, magically, the instrument sings out. She sets the heel of the violin into her waist and screws the

squeaking peg of the G string tighter. We flinch away, waiting for the string to break under the strain and lash all three of us. The pitch of each string in turn edges grudgingly upwards. She plays a scale or two, an arpeggio.

Then out from the inexhaustible recesses under the stairs comes a corroded nickel music stand and a mildewed leather music case. More setting up. My sister and I wait in an agony of anticipation.

Our mother takes a white-spotted, dark blue silk scarf out of the case and holds it against her collarbone as she tucks the violin between shoulder and chin, then takes her hand away from the violin to turn the pages on the music-stand. The instrument remains improbably where she has put it, projecting unsupported into empty air.

And then she plays. The violin part from Rossini overtures â

William Tell

,

The Thieving Magpie

. Other light classics â

The Post

Horn Gallop

,

The Blue Danube

. All things of the kind of that she must have played in the Queen's Hall Light Orchestra. I recall virtuoso showpieces, too â Tartini's

Devil's Trill

, for instance. But this is scarcely possible. Not after one year at the Academy and twenty years of Harrods and housewifery. My memory is being assisted by the family talent for improvement once again.

So much about my mother I have forgotten since then. The sound of her voice. The exact words that she spoke. Even what music she played us. But not the fact that she played it. Not the excitement when she gave in to our pleading. Not the laborious restringing, the tightening of the bow, the blue silk scarf. The curve of her bent fingers on the fingerboard. The bold mellow vibrato, conjured out of nowhere but a hollow box and nothing but catgut and a swatch from a horse's tail, singing through the house.

What was

she

thinking about as she played, I wonder now. Did it take her back to the spring of 1919, when she had just met handsome Tommy and she was at the Academy, with all the time and all the music and all the happiness of the world in front of her? And what did she feel about the way things had turned out? Well, she had us, her two children. We weren't quite as big an audience

as she might once have hoped for, but listening as raptly and appreciatively as any audience ever could.

And she had Tommy. It's not the kind of thing one ever wonders about as a child, but, looking back as objectively as I can, I think they loved each other. Tom Frayn and Vi Lawson. Mr and Mrs T. A. Frayn. Tommy and Vi. I remember their having one row, and how shocked by it my sister and I were, and if I can remember that one so clearly I suppose I'd also remember if there had been any others.

I've no idea which year it was, or what it was about, though I have a feeling that it was something to do with money. It's a Saturday morning, I know that, and we're having breakfast in the kitchen. Suddenly something has gone wrong with the conversation. Their voices are loud and hard, and my mother's running out of the room. My father sits on at the table in silence, too angry to look at us. My sister and I finish our breakfast without daring to speak, then creep, still chastened, upstairs to our room. And there's our mother, not in her room but in ours, sitting on my bed. She manages a smile for us. We look at her fearfully, still saying nothing. She has been crying. She sits there like a rueful child.

One row, just so as my sister and I know what a row is, in all the thirteen years I saw them together. I think that, yes, perhaps our mother

had

found something of the happiness that had seemed to be opening out in front of her that spring in 1919, in her fifteenth year.

Or is the quarrel that Saturday morning something to do with the strains of life with a mother-in-law? My grandmother must have been living with them for six or seven years by this time. Where is she when the storm breaks? I think I'd remember if she'd been with us in the kitchen. She has nervously fled, I suppose, at the first intimations of trouble. But then where is she while my mother is playing the violin to us? You might have thought she'd be proud to see her daughter resurrecting her old skills, her lost promise. The only members of the audience, so far as I can recall, though, are my sister and me. Can our mother have chosen days when Nanny's out of the house? But Nanny's

never

out of the house! The very thought of such a thing, and even I can see the bolting milk-horse that will trample her, the sudden thunderstorm that will bring her down with double pneumonia to the early grave she has so many times predicted.

So she must have chosen not to be present. Perhaps the almost human voice of the violin speaks to her too painfully of the family's lost hopes, of the way poor Bert's success in persuading her to brave the perils of the North Atlantic and the Midwest was so cruelly followed by his failure to persuade the shoppers of London to sleep on sacks of straw.

She must be in the house somewhere, and there's only one room it can be. Her own room. Her mysterious private sanctum, the downstairs back bedroom, separated from the kitchen and the rest of the house by the darkness of the windowless corridor. We get only the most occasional glimpse inside. An entire life is packed into that room â I suppose most of the contents of 1 Gatcombe Road. Ãtagères and chiffoniers covered in little trinkets and

mementos. Faded sepia photographs of faded sepia people. The old oil painting of herself as a girl, with the converging slant of the mouth and eyes that I've inherited, and the red-gold hair that I haven't. Silver teapots, porcelain shepherdesses, religious-looking books with dark leather bindings and gilt-edged pages. Gauzy scarves and wraps and throws. Discreetly shaded lights. Everything is rose and russet, and disappears into darkness in the depths and corners of the room. Pomanders, bowls of patchouli and little bags of dried lavender make even the air delicately antique. There's a pad of the mauve paper on which Nanny writes endless letters in her sloping hand to her sister Lal. And all of it in a room twelve feet long by nine feet wide.

Do any of the other families in the street have live-in grandmothers? I can't remember any, but in the electoral register I see a number of spare female names whose owners I can't place; perhaps they're all grandmothers hidden away in dark back rooms. Having a widowed parent living in the house is after all a common enough arrangement. The oddity in this case is that Nanny

isn't

widowed. She isn't divorced â she isn't even separated in any normal sense of the word. She just happens to have a husband who can't afford to give her a home. He's âfending for himself', as Phyllis puts it, in digs in Crouch End. And at weekends he comes to stay.

This is surely an arrangement unknown at the Kidds' or the Dennis-Smiths', even at the Davises' or the Barlows'. My poor father has got both Vi's parents on his hands. So far as I can tell, though, he gets on well with Bert. Goes off with him for a pint at the Spring Hotel in Ewell Village on a Saturday night. Takes him with us on spins in the country â us in the car, Bert following on his drop-handled iron bicycle, wearing his Harris tweed plus fours and sucking his pebble against thirst. Bert â Pa to me â sits heavily around the house in his braces whistling, often with a tangle of broken clock springs and loose brass cogwheels spread out in front of him. (How do we come to have so many defunct timepieces?) He keeps a lot of his stuff mixed up with our own chaotic arrangements. His cannibalised violin is under the stairs. His bicycle is in

the garage, making it difficult to squeeze between it and the car to get at all the junk beyond. The St Ogden's St Bruno Flake tin that contains his watchmaking tools lives on a shelf with the jam-jars and rusty skewers in the coalshed. His chess set is in a linen bag with our own odd loose chess pieces and defective packs of cards in the sideboard.

Where does he sleep, though? Not in Nanny's room, certainly. He's a large man; there's no room for him in there. He'd break shepherdesses and chiffoniers every time he turned round. I suppose it's on the settee. I go out into the garden on a fine, hopeful summer's morning when the air's still cool and the dew's on the grass, and there's Pa, up already, perhaps unable to sleep on that settee, since he's about the size of a settee himself. He's in his braces, with his hands in the pockets of his plus fours, contemplating the progress of the beans and the lettuces, and whistling, whistling. I stand beside him, my hands in the pockets of my shorts, also giving my father's efforts a critical once-over, also attempting to whistle. I glow in the radiance of his wonderfulness.

*

My father is also often playing host at the weekends to his own family as well as his wife's â all of them at once, sometimes. It's Sunday teatime, and both wings of the dining-room table have been extended. On the table are many plates of sardine sandwiches, and little jars of fish paste and meat paste, with dishes of homemade blackcurrant jam and fans of white and brown bread-and-butter to spread it on, celery and watercress, scones and teacakes, rock cakes and fairy cakes, fruit cakes and Victoria sponges.

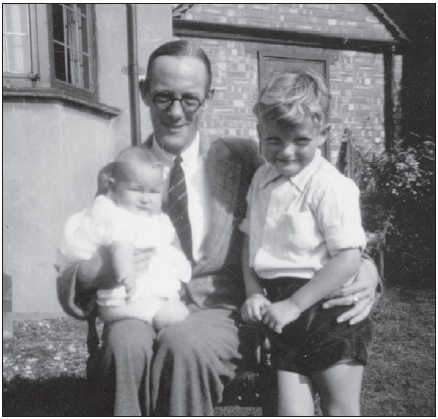

Around the table are wedged an amazing number of people. Tommy and Vi, of course, and my baby sister. Bert, aka Pa, now with a Fair Isle sweater politely concealing his braces, taking up a good deal of what little space there is available. Nanny, or Nell of course to most of the family. A second Nell, or rather Nellie, my father's eldest sister, and her husband Frank; Uncle George and his wife, who's a third Nell, or rather Nelly with a

y

, and their son Maurice; Auntie Daisy and a second George; perhaps their

sons, Philip and John; Mabel and Mrs Murkin. Mrs Murkin? Mrs Murkin is the former next-door neighbour from Devonshire Road, whom Mabel still goes back to see each day. Mabel and Mrs Murkin: the names fit together in my memory as naturally as George and Nelly.

My favourite relative among all these, apart from my grandfather, is Daisy. She's almost as deaf as Mabel, but as chirpy and restless as a baby sparrow. She has perhaps got even further away than my father has from those two rooms in Devonshire Road; the George she has married is a silent, unreadable man who began his career at sea as a naval officer, and who now has a solidly respectable job designing mines for the Admiralty. Daisy moves him and their two young sons restlessly back and forth around one address after another in the Portsmouth area. Their younger son, my writer cousin John, has been reconstructing the story for me. First there are two furnished flats in Southsea, and then two houses in Gosport, on the other side of the harbour. Here George begins an affair with a neighbour's wife, and Daisy moves the family twice more around the Gosport side to get away from her, then inland to Fareham, to get further away still. She has a breakdown. They move back to Southsea. According to my father (are we to believe this?) she tends to move without consulting George, so that he never knows from one week to the next where he's supposed to be coming home to.

Somewhere around this point he rebels. He resigns his career as a mine designer and takes off with the neighbour's wife from four or so moves back. But his liberation from the tyranny of the pantechnicon is brief. Daisy sends him a telegram, signed by their son Philip: âCome home at once mother dying.' She then goes to the Admiralty and talks them into taking George on again. Daisy

is

in fact dying â she has leukaemia â and George grudgingly agrees to stay with her until the end comes. It's not a happy arrangement, but Daisy does her best to make a fresh start â by moving them again, all the way up the Southern main line to Guildford. So there's a painful logic to all this restlessness, though John agrees

that Daisy perhaps did also like moving for its own sake. (He and his wife seem to have inherited the taste â they've moved ten times themselves.) From Guildford Daisy moves to Bramley, then on again to Liss, and she's just bought yet another house in Goring-by-Sea when death finally halts her odyssey. She's only fifty-four.

So there they all are, everyone talking at once, some of them too softly to be heard even by the ones with hearing, some of them with so little hearing that they probably don't realise that anyone else is talking. What are they all talking about? They're struggling to sort out George from George, and Nelly from Nellie and Nell. They're protesting that they're unable to eat a third or fourth rock cake, but will perhaps try a slice of that delicious-looking sponge. âAnother cup of tea, Nelly? Sorry â I don't mean Nelly â I mean

Nellie

. More tea?' â âFour what, love?' â â

Tea

. More

tea

?' â âOh, I couldn't, love, but I'd love another cup of tea.' â âAnd

four

lumps, is it?' â âNo, love, no more â just four.'

Apart from the eatables what they're talking about mostly is the old country â North London. Some of them are still there, around the Seven Sisters Road. Others are scattered â George's family out to Finchley, Daisy's to wherever she's got to by now in Hampshire or Surrey, Tommy and Vi to Ewell. All of them still thinking about Holloway and points north. The familiar names keep coming round. The Seven Sisters Road. Archway. Tufnell Park, Finsbury Park. Crouch End, Alexandra Palace â¦

A dozen or more people around the table, and somewhere among them there must be a chair for me. It's unoccupied, though. I'm on the floor, under the table, and refusing to come out. The trouble is not the press of people, or the din of North London place names. It's my Uncle George. Not Daisy's George â Nelly's George. Or to be precise, it's Nelly's George's eyebrows. They're enormous, and dense, and pitch black, and they beetle. They beetle most terrifyingly out from his rather small and conciliatory face, and even Richard Hannay or Bulldog Drummond would turn and run at the sight of them. Uncle George, unlike his cheeky baby brother, my father, is a shy and softly-spoken man, but these qualities are

completely outweighed by the horror of those terrible appendages, and I'm proposing to stay under the table until they've gone home.

My wonderful grandfather negotiates a compromise: I can sit in his lap and keep my eyes closed. I climb into that vast, warm, luxuriously upholstered human settee and eat fairy cakes by touch. After a while I feel so secure that I risk opening one eye a little and taking a peep. The great black entanglements on the other side of the table are beetling away at me just as menacingly as before. I close my eye again.

*

These dozen, perhaps fifteen people, are wedged around the table in a room eighteen feet long by twelve feet wide. I know the dimensions of the dining room, as I do of Nanny's room, so precisely because, many years later, I made a television film about the streets where I grew up, and I acquired the plans of the house from the local council. While I was making the film I got myself invited back by the then occupiers. Your childhood surroundings are said to look always distressingly small when you go back with an adult eye. I can't say that my old home did, though. It had been smartened up beyond recognition, but the general layout was entirely familiar â and it seemed rather spacious.

Particularly the dining room, the biggest room in the house. But then, when I went back, there weren't fourteen or fifteen people sitting in it, and a table which, with its leaves extended, must have been about nine feet long, but it wasn't the only thing occupying the available space. Against the long wall on one side of the table was a sideboard, and on Sundays, when the relatives came, a tea trolley with my grandmother hovering anxiously over it. On the other side of the table was a bureau, with a sloping lid which could be let down to make a writing surface, and which sometimes suddenly let itself down with a sharp crack under the pressure of all the junk taken off the tea table and wedged behind it.

I've been making a few rough calculations. If you add up reasonably plausible widths for the sideboard, the table and the bureau, it

leaves a space of about two foot six on either side to accommodate the guests, and allow access for people bringing round the cups of tea and the slices of sponge cake. A good job, perhaps, that the Frayns are all so wispy â particularly since all fourteen or fifteen of the people at the table must be sitting along its two long sides. Why can't some of them be sitting at either end? â Because the southern end of it is hard up against the French windows, and the northern end is pressed against the back of the settee.

A settee? In the dining room? Slightly surprising, now I come to think about it after all these years. And why is it pushed up against the table? It can't be more than about three feet deep, which must leave another six feet of dining room free beyond it. Couldn't it be moved a little further away from the table?

Not really, because on the other side of the settee are two armchairs. It's not just a settee, in other words, it's a three-piece suite, and on the other side of the three-piece suite is the fireplace. There has to be a foot or two left between the fire and the knees of the people on the three-piece suite. You could safely sit with your feet in the grate in summer, it's true⦠No, you couldn't, actually, because the gap between knees and fire is also the flightpath running laterally between the darts board on the right-hand wall and the dart-launching position near the left-hand wall. Even if no burning coals were falling on your feet there would be ricocheting darts falling on your head.

Leaving aside the question of whether this is a good place to play darts, why is there a three-piece suite, upholstered in brown mock leather, studded with round-headed brass tacks, in the dining room? Because we've nowhere else to put it, obviously. But we do! We have another reception room, as an estate agent would call it, twelve feet square, called the lounge. The lounge is presumably the place where you lounge, and if you're lounging it would seem natural to have a settee and two matching armchairs to do it in. Why isn't the three-piece suite in the lounge?