My Guantanamo Diary (30 page)

Read My Guantanamo Diary Online

Authors: Mahvish Khan

“I want my children to have a love, to have

meena

—affection—

for Afghanistan,” he explained. “I want them to see to their homeland

while it is free.”

When I called his brother Ismael hoping to get together, I learned

that Mousovi and his family had gone to Gardez for a wedding. So, I

decided to hitch a ride to southern Afghanistan with a local aid

worker. The drive was beautiful, with stunning mountains and the

changing colors of autumn drenching the landscape.

Our car pulled up to Mousovi’s house, and he came out to greet us,

Ismael following close behind.

“Mahvish-jaan, I can’t explain how happy you’ve just made me,”

Mousovi said, clutching my hand.

I was itching to give him a big bear hug, the kind I’d give my

friend Georges from Miami. Georges would show me just how

happy he was to see me by giving me a monster squeeze and picking

me straight up off the floor. I think I fantasized a dramatic reunion

like that with Dr. Ali Shah. But Afghan culture and society throws

up so many intricate barriers between men and women that I had

to settle for the tight grip of his hand and his carefully chosen

words. It was the same at Guantánamo. There were many, many

times when I wanted to console prisoners with a hug. But other

than with Haji Nusrat, it never happened; the culture inhibits it.

I smiled at the doctor and chose my words as carefully as he had.

“Dr. Sahib,” I began, “I’m so glad to finally see you here in your

home. It means more to me than I can explain to you.”

“May Allah always keep you happy,” he said and then, “

Raza, raza

—Come, come,” as he ushered me into the house, where I met

his mother, a little old lady who immediately embraced me tightly

and proceeded to plant kisses all over my face and head. She held my

hand for the next several hours. “I feel like my daughter has come to

visit,” she announced. I channeled the affection I felt for Ali Shah toward

his kind mother.

The doctor told the story of the moment we first met, when both of

us were nervous about whom we would be meeting. I expected a terrorist;

he, perhaps an abusive interrogator. I walked in and saw a

nervous pediatrician standing at the back of the room. He saw me

under an Afghan shawl and mistook me for his sister. “I really

thought it was Parveen, that she had come to see me somehow,” he

said.

The sight of Dr. Mousovi at his house was slightly surreal. I had

only known him as a gentle, white-bearded man with chains around

his feet. Seeing him at home with his family, just as I’d always

prayed he would be again, allowed me to feel the weight of everything

I’d held back during our Camp Echo meetings. He’d been the

first prisoner I met, and the impact of that initial meeting was

greater than most of my meetings with other prisoners. He was the

first to break down my biases and to show me what sort of injustice

my country had committed against good, kind people. I realized that

I hadn’t allowed myself fully to feel all the effects of that until now,

when I saw Dr. Ali Shah safe and free.

Being at his house was like being at the home of an uncle. I

poured green tea for the doctor and his mother into small, clear tea

glasses, and they filled bowls with red pomegranate seeds. I helped

his mother carry in dishes of rice, yogurt, meat, and eggs. They were

wonderful hosts; there were no formalities. We talked, walked in and

out freely, sometimes sat on the couch, sometimes on the floor. And

following custom, everyone encouraged everyone else to eat.

I couldn’t stay late because I’d been told that it wasn’t safe to drive

through the south at night, but I ended up lingering anyway. It was

hard to leave. Mousovi and his mother kept pressing me to stay for

the wedding of a relative from the extended family. His nieces presented

me with sparkly orange wedding bangles, and his mother gave

me a pretty embroidered white shawl.

When I had to go, his mother embraced me tightly, while Dr. Ali

Shah sat on the floor on his knees looking on. “Our hearts don’t

want you to leave,” he said. “This is your home too.”

I wasn’t good at this impromptu poetic word game, and I was a

bit overwhelmed at seeing him so happy, so I simply said, “I’ll see

you again soon, and we’ll stay in touch.” As he walked me out, he

told me how much our friendship meant to him.

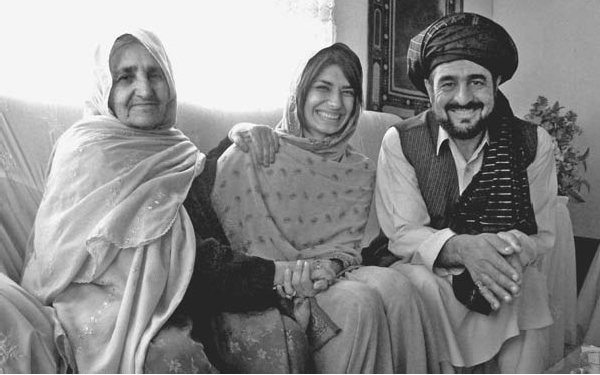

Dr. Ali Shah, his mother, and I at his Gardez home.

Photo by Lal Gul.

“We’ll have this special thing forever, though it started in the most

unlikely of places,” he said.

“I know what you mean,” I replied. “You’re like family.”

I wished him fun at the wedding that night. “Weddings are happy

occasions,” he said. “You coming to my house today was like the

happiness of two weddings for us.”

I think that made up for the bear hug.

Some of the men I met at Guantánamo have been released, but

many have not. Haji Nusrat’s captivity had a bittersweet ending.

In August 2006, the eighty-year-old was released as unexpectedly

as he’d been arrested. Like Ali Shah Mousovi, he was given a hero’s

welcome in Yakhdan, his native village in Sarobi, by hundreds of

visitors who had streamed in for the homecoming.

Nusrat’s family immediately began to entertain well-wishers, including

a few Americans—U.S. military officers stationed at a

Sarobi base who dropped by to see what all the commotion at his

home was about. The American soldiers were treated just as warmly

as the Afghan guests, invited in and offered green tea.

“They greeted me and said they were sorry for what had happened

to me,” Nusrat told me later. “I told them I had forgiven

them.”

I trekked to Sarobi in November 2006. I was greeted by Abdul

Wahid, Nusrat’s son, a tall man with light brown eyes, who led me

into a guesthouse room lined with red cushions. I took my shoes off

and sat down as someone brought in pastries and nuts and Abdul

Wahid poured tea.

I could hear the sound of Haji Nusrat’s voice outside. He was

speaking to some visitors, who continued to stream in four months

after his release. He didn’t know I was

coming, so when he stuck his head

through the window to see who his

next visitor was, his face lit up in surprise.

His sons helped him into the

room, and he sat next to me on the

cushioned floor.

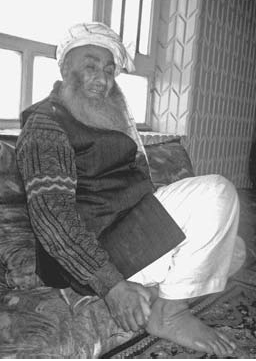

Haji Nusrat.

Author photo.

“

Bachai

, you kept your promise. I

knew you would,” he said.

“I’m so happy to see you here,” I

told him. He was so different from the

way he’d been at Gitmo, much calmer

and more peaceful.

“

Bachai

, what happened to me was

cruel,” he said. “I suffered a big injustice.

It was not a small injustice.”

I asked him about his release.

“My release,” he said leaning back into the pillows, “left me

ne khushala, ne khapa

—not happy, not sad. I didn’t want to leave my

son behind.”

When he was led out of Camp 4, Nusrat said, “Izatullah came up

to the edge of the fencing and said, ‘

Khudai-pa-aman

—May God’s

peace be with you.’ I gave him my hand, and then I had to leave

him.”

“He must have been happy for you, but also sad,” I said.

“No, my son was happy. He was happy that his father was being

released. I was sad.”

I spent the day at Nusrat’s because Afghans are so insistent that a

guest stay as long as possible. An Afghan guest is typically offended if

tea is not offered. Then, the host usually insists that the guest par-

take of the next meal. So, when lunchtime came around, there was

no question that I would be staying. We went into another room,

where I was surprised to see a satellite TV, and had an elaborate

communal meal. Nusrat sat next to me on the floor. I was a little surprised,

again, to see him drink Nestle bottled water instead of tap or

boiled water. He handed me a can of Pepsi, and his sons and grandsons

brought in two-foot pieces of fluffy bread. They laid out

chicken, lamb, rice, spinach, soup, and potatoes on a floor mat.

As people bustled about, I talked quietly to Haji. Then, he remembered

something and started yelling for his son, who had stepped out

of the room.

“

Waa Abdul Wahiddaa

!” he yelled. “Come in here and bring

that box.”

I was amused at the way he ordered his son about. Abdul Wahid

waited on his father hand and foot and never complained.

“

Waa Abdul Wahiddaa

!”

Finally, the twenty-seven-year-old came in holding a box wrapped

in sparkly blue-and-white paper and tied with long, colorful ribbons.

As he walked toward us, holding the box out to me, Nusrat stopped

him.

“Give it to me. I want to give it to her,” he grumbled.

Abdul Wahid passed him the box, and Nusrat passed it to me.

“As I have said before, you are like my own child,” he said. “Our

friendship will be strong and will last forever. Don’t ever let it go.”

“Of course not, I wouldn’t,” I responded. I thanked him for the

gift. I opened it, careful not to rip the shiny wrapping. It was a thick

brown embroidered shawl. I knew I would treasure it for years to

come.

Nusrat introduced me to his extended family and other guests who

had stopped by for lunch and told them the story of how we met.

Then, we ate out of assorted plates and bowls of food, using the bread

in place of utensils. Haji placed small saucers of salt and pepper in

front of me and put pinches of both on my chicken and spinach. As we

ate, I asked Baba, as he now insisted I call him, about his health. He

paused between slurps of brothy soup and asked a favor.

Haji Nusrat and his son Abdul Wahid having lunch in Sarobi.

Author photo.