My Name Is Mary Sutter (26 page)

Read My Name Is Mary Sutter Online

Authors: Robin Oliveira

Chapter Thirty

12th November, 1861

Dear Mary,

Are you receiving my letters or are you not answering me? I have heard nothing from you; sometimes I fear you are not even alive. Acknowledge me that at least. I will do what I can with Jenny, but I am uneasy. I see her still as my child, and you as my esteemed friend. It is not fair, I know, but you must come and help me. I know you are grieving Christian, as am I. Let us find solace together.

Amelia

25th November, 1861

Dear Mother,

I have received your letters. Please forgive my unforgivable reticence. I plead an excess of work, which is true, but I also have not written because I cannot face coming home. (You know why I cannot; do not make me say it.) And I grieve Christian every day; you cannot imagine how my heart has broken.

Please do not be frightened about Jenny. You fear too much your own emotions. Did you not teach me everything about midwifery? By anyone’s estimation you are more than capable of bringing Jenny on your own safely to the other side of her confinement. You must trust yourself, though you may believe that it is unfair of me to disregard your distress. But it is not purely self-protection that compels me to encourage you. I have learned that it is possible to endure anything. And I have duty to render here; hundreds of men who need me. In light of such need, I cannot abandon them or Dr. Stipp, who relies on me. (Dr. Stipp is the man who runs the hospital here; he has agreed to apprentice me.)

Mary lifted her pen from the paper and glanced out the window onto Bridge Street, dark except for a swinging lantern, its owner on subterfuge of his own. How easy it was to justify. Wasn’t need the same excuse she had given to Thomas?

In light of your distress, I beg you to consider my forbearance. I never told Jenny how sad their marriage made me. This at least, must count for something in your estimation. I hate to ask you to be generous to me after all you have taught me, but I entreat you to understand. Jenny has you, which is more than enough; does she also need me? Two midwives in attendance, when men here are dying for lack of food?

Please do not think me heartless. Obligation calls me both places, and, trusting you, I choose the greater need. I do not love you or Jenny any less—

Was that a lie? Did she love Jenny less?

—but you must understand that either way, I will think poorly of myself, for there is betrayal in both decisions. And perhaps, if I am truthful, I have chosen to protect myself. There, I have said it. Think as ill of me as you like now. But you will do well by Jenny, or else I would come in an instant.

Do not worry, Mother, for you know everything there is to know in order to bring your grandchild safely home. I truly believe that my presence would make no difference in the end for Jenny. I ask one last thing: Please keep my distress from Jenny and do not show her this letter. Perhaps it is cowardly of me, but I fear knowledge of my weakness can do her no good.

Your loving daughter,

Mary

Mary put down the pen on the little desk she had fashioned from wooden crates. The candle was nearly burned out. There were times at night when despair showed no mercy. Why couldn’t she go home and offer her mother this one thing?

I have learned that it is possible to endure anything.

What was she so afraid of? Would it really hurt her to shepherd Thomas’s child safely into the world? Or was she, like her mother, too much afraid of her own emotions?

In the womb, she and Jenny had shared everything, their arms and legs entwined in a seeming eternal embrace, a grasp she feared now had spawned more competition than cooperation. But what was fair when selfishness collided with heartbreak? Mary buried her head in her hands. What was required of a sister?

Cold knifed into the window cracks and up through the floorboards as Mary studied the letter she had written, thinking that it was possible that she knew nothing at all of kindness.

She set aside her letter to Amelia, chose a new sheet of paper, and dipped her pen again in the ink.

Dear Jenny,

I am writing to apologize that I am unable to come home for your confinement. The work here is necessary and demanding and there are so few of us to do it. Do not be afraid, my sister, for you know that Mother will protect you and keep you through the storm. Please endure the best you can; it is best not to fret too much, but to accept what labor brings. Let your body do the work, and then you will have Thomas’s child, and your happiness will be complete.

My love,

Mary

Mary let the ink dry, then folded and stuffed the letters into their separate envelopes, sealing them with wax so that she wouldn’t be tempted to read them again in the morning, when a less fraught perspective might change her mind. But her refusal was not abandonment. Her mother was only afraid, out of love. And when Jenny’s time came, that same love would render her mother more competent, not less. She was tempted to tear open her mother’s letter to tell her that fierceness in a mother was what every laboring daughter needed, when a knock came on the door. It was Monique Philipateaux, carrying a candle, saying that two men had died of their fevers, and would Mary please come, for their roommates were ill as well, and no one knew what to do.

Without a glance at the envelopes, Mary snuffed her candle, threw a shawl over her nightgown, and hurried out the door.

Chapter Thirty-one

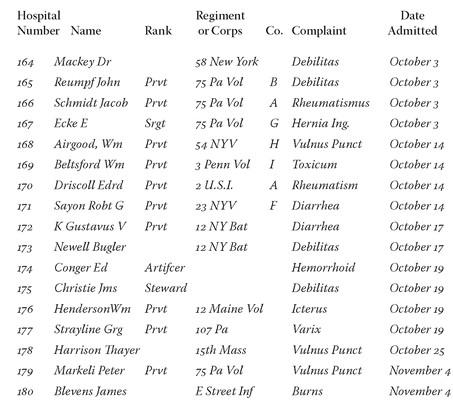

Register of the Sick and Wounded, Union Hotel Hospital, November 1861

“Dear God, Mary, what are you doing up?” Stipp asked.

Mary dropped her pen, smearing the new ledger’s pages with ink. The scraping of the pen against the page had been the only sound she had been aware of, though at night the Union Hotel Hospital was a noisy organism. Tamped down, shuttered in by the cold, its occupants groaned and prayed both for daylight and for delivery from the misery of the dying men alongside them, but the collective chorus had disappeared for Mary as she had worked.

She said, “I might ask the same of you.”

Stipp dragged toward her from the hallway door and sank down beside her in a chair. A gray army blanket smothered his shoulders. Clouds of vapor escaped from his mouth. He had lain awake in his room for four hours, powerless as life ebbed noisily away from the men in his charge, thinking that he too was closer to dying with every passing minute. He had fled his straw-filled coffin of a bed to discover Mary—young, indefatigable Mary—writing away, scraps of paper and scribbled notes piled around her as she tried to impose some kind of order on the chaos that was the Union Hotel. The manual Stipp had been sent by the Medical Department,

Handbook for the Military Surgeon

, rested at her elbow

.

Stipp had been looking for the handbook for two days.

“It’s past three o’clock,” he said.

Mary peered at the tall clock still in its place at the far end of the dining room. It had been too heavy for the owners to cart off when the government had taken over the hotel.

“It’s three-thirty.”

“Two hours and the day begins all over again. Aren’t you tired?” Stipp asked.

“The Medical Department want us to keep track of all our admissions. They want us to backtrack as far as we can remember.” Though it was the second week of December, Mary had been recording the names of the soldiers they had admitted in October from the battle near Ball’s Bluff, north along the Potomac. It had been another rout—the Union Hotel had been the closest general hospital, and for a period of two weeks they’d received wounded shipped down the C&O Canal on barges and offloaded and carried up the hill on stretchers. Some were from the field hospital at Poolesville, some from a makeshift hospital in a barn on the Maryland side of the river, where several amputations had been performed. The wounded crowded the hotel—it had been a week of no sleep, again. Fresh surgeries, another amputation, this one of an arm. The new dead house Miss Dix had badgered the quartermaster to build them had received the arm like a coffin. Sometime later, a driver came to cart it off, and it lay uncovered in the back of the wagon, and all the people on the streets of Georgetown and Washington shuddered as it had trundled by.

Mary dipped the pen into the last of her ink. A candle burned on the table. The fire had died down about ten, but she was too mindful of the dwindling supply of firewood to light another. “If you’re too tired, Dr. Blevens would probably be eager to take your place on morning rounds.”

“I’m not tired.”

Blevens’s hands were much better. The slippery elm seemed to have done the trick. He was leaving within the week to work at the hospital at the Patent Office.

To Stipp, the scratching of the pen sounded like the scrape of knife against bone. Stipp studied the curve of Mary’s long neck. He liked to study her when she was absorbed in work, when her thoughts were directed to a task at hand and she had no awareness of anyone around her. He often imagined that when she delivered babies, she exhibited the same quiescent concentration, an aloofness that nevertheless was eminently trustworthy.

“Is Peter any better?” he asked.

How is the boy? The boy is well.

“He is. He seems to have come around. He drank a cup of water today. And the edges of his wound are not suppurating much.”

Stipp nodded. He did not know why he’d asked her; he believed she was far too attached to the boy to judge his medical situation dispassionately. He’d been dropping in on Peter all afternoon and feared that he was worse off than before. He choked too often when he drank; Stipp believed it was affecting the poor boy’s lungs. He would not argue with Mary now, though. It was the dead of night and he craved a moment free of pain.

Mary lifted her pen from the page. “I don’t know the rank of the men admitted from Ball’s Bluff. And if I have to record every person admitted to this hospital into this ledger, we are going to run out of ink.”

She read out loud the next page: “Date Returned to Duty, Deserted, Discharged from Service, Sent to General Hospital, On Furlough, Died, Remarks. How are we supposed to know all of this? They don’t even know who’s in the army when they’re in their regiments. Vulnus Puncture. Why don’t we just write ‘gunshot wound’?” Mary said.

“The Latin makes it less vulgar.”

“Or more. Vulnus.”

The building cracked in the cold.

“Christmas is coming,” Stipp said, endeavoring to keep his voice even.

Mary lifted her hand from the page. The pen hovered in the air, a drop of ink, like blood, forming at its pointed tip.

“You won’t persuade me.”

“I have seen you reading and rereading your letters. You cannot claim indifference.”

“I do not claim anything like it.”

“I will write a furlough for you, if Miss Dix won’t.”

“I have not asked her.”

“Shall I ask her for you?”

Mary capped the ink bottle, wiped the nib of her pen, and rose from the table, leaving the ledger’s pages open to dry.

“You are very stubborn,” Stipp said.

“You make that observation as if you have just realized it.” Mary reached for the surgery handbook, but Stipp forestalled her with a hand on top of hers.

“I am almost finished reading it,” Mary said.

“Your mother wrote to me. Grief festers, Mary. And you will regret not going for your sister.”

“You are not my father.”

“No. I am not. But I love you all the same.”

Her hair fell like a curtain across her face, and she tugged her curls back into their combs. Stipp loved even the frantic nervousness of these gestures, the way she worked without even knowing what she was doing. “It is just a fact, Mary. And we might as well say these things.” He did not say,

Because death hovers in the wings. Stalks the wards. Prowls in the night.

Her hands stayed as a corona above her head, then she slowly let them fall. She managed to keep the pity from her eyes, but just. “You love me?” She said this slowly, as if he were already dying, or as aged as he felt in the face of such youthful ambition.

The young woman who was so adept at compassion—matter-of-fact and kind without displaying any pity—now looked at him as if she had never learned that to pity a man was to kill him.

He let a lying smile break from his face, withholding all sorrow, though his eyes watered. He was grateful that it was the dead of night, and the creeping dawn ages away. Oh, he felt old for the foolishness of love, for its indiscriminate yet accurate aim.

“You see,” he said. “How could I not love you? You are the daughter I wish I had. The one I would be proud of.” He said a silent apology to Lilianna, and to Genevieve, his first love.

But darling, life goes on, and this pain is agonizing evidence

.

Would that there were only the scraping of the pen, the illogical, record-keeping rasp, the focus that renewed her, buoyed her up, let her believe that doom was not inevitable. The world was ending, but here was an offer of love.

Irrepressible Mary, speechless. Dr. Stipp vaulted to wisdom. To age. To rank, even. “Don’t worry,” he said. “It is better, isn’t it, than our disliking one another?” Said it with a straight face, as if such lies were believable.

“Of course,” Mary said.

Another mercy dispensed, to pretend to believe the second lie. She would feign belief in a third and a fourth, and then another—endless numbers of them—to keep this man from dissolving. She wanted to say,

It is only the war that makes you love me. It is only the night. It is only the chaos. See

, she wanted to say,

the ledger? It is our only hope.

As if to confirm, Stipp took up the ledger and made careful examination of her entries. The clock tolled the hour. Four o’clock. God, such beastly things were the hours of the night. “I believe your page is dry now.” He shut the ledger and handed it to her, as if it were his heart.

They left the room together and separated at the top of the stairs, Mary taking the candle and Stipp feeling his way back to his bed in the dark.