My Name is Number 4 (25 page)

Read My Name is Number 4 Online

Authors: Ting-Xing Ye

“There is no one else here,” said one, who looked to be in her fifties. She smiled. “Yours is the only exam.”

In my nervousness I completely missed the significance of her words.

“I am Teacher Chen from Beijing University,” she went on. “Teacher Xu is from Qinghua University.”

I nodded at the younger, stern-looking woman.

“We are recruiting students from East China,” Teacher Chen explained.

My brain began to function. “Do you mean that you came down here just for one candidate?”

“This by no means suggests that you will be successful,” Teacher Xu cut in, indicating that I should sit down. “Now, let’s begin.”

She handed me a piece of paper on which a few passages in classical Chinese were printed. “Please translate them into everyday speech.”

I took out my pen and began. It was not difficult; my first semester in middle school had been devoted to this kind of work. About an hour later, I put down my pen. My second test was oral. Teacher Chen gave me a text in English called “We Have Friends All Over the World” and asked me to read it out loud. I didn’t need to translate, just read. It was a piece I had read over many times at night under my mosquito net, for it was in one of the books Number 2 had given me.

Now all my studying in isolation, while my dorm-mates played cards, chatted or crocheted, paid off. I read out the text, clear and loud. Teacher Chen could barely contain her pleasure. Teacher Xu maintained her serious demeanour and reminded me that, although I had done well, that didn’t mean I would be selected.

“One red heart, two preparations,” she admonished me—a good person should be prepared for failure as well as success—a common expression around exam time at school.

I stood up and forced myself to look her straight in the eye. “Please,” I stammered, “please let me go to university. I have been here for six years, working in the paddies the whole time.

Don’t you think I have got enough education from the peasants, as Chairman Mao wishes? I promise you, if you accept me, I’ll never let you down.”

When I turned around and left the room, Teacher Chen followed me. As we shook hands, she looked into my eyes and squeezed my hand.

On the way back to the village I was deep in thought. I had done my best and said what I wanted to say to the two teachers. Now I would have to let Fate take care of the rest. And yet, why was there only one person to take the exam? And what was Teacher Chen trying to tell me when she squeezed my hand?

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

B

y that time I had been “dating” Xiao Zhao, the young man in the canteen, for a few months—the old prohibitions had been relaxed. It was the first relationship for both of us, although he was much sought after by the pretty women in our village. Nicknamed Huang-di—King—for his good looks, Xiao Zhao was three years older than me, the seventh of eight children in his family. His mother had died of a heart attack when he was seven and his father had remarried.

Like mine, his parents had been Shanghai business people. Though we came from the same background and had arrived at the farm on the same day, we had walked different paths. While the majority struggled in the paddies, buffeted by the northwest wind, he had worked in the canteen from the beginning—one of the plum jobs in the village. Xiao

Zhao hadn’t suffered persecution like the rest of us with tainted blood. In fact, under Representatives Zhao and Cui he had been designated a “Five Goods” Worker—outstanding in five stated areas of political correctness—every year.

My first contact with Xiao Zhao had come after I was released from house arrest. I had been summoned to the brick house and told by Cui to prepare for another struggle meeting that night. By the time he let me go, supper was over. I took my food tin to the canteen, entered the darkened dining room and knocked on one of the serving windows. Xiao Zhao opened the window, took my tin and returned a few moments later, having gone to the trouble of heating up the food for me. I was grateful for the kindness and thanked him.

“Do you really think what you are going through is worth the trouble?” he asked, handing me the food through the serving window. “Why not just go along with them? Take my advice, don’t push against the wind.”

I didn’t speak to him again for two years, then a very strange thing happened. I was at home in Shanghai and my two-week

tan-qin

was drawing to an end. Number 3 found me in a nearby store where I was doing some last-minute shopping for my return.

“There is an old man in our apartment,” she exclaimed, “and he has a big parcel with him. He says he wants you to take it back to the farm and give it to his son.”

I was at a loss. No one at Da Feng had asked me for a favour.

“He’s well dressed,” Number 3 went on, “with a heavy Ningbo accent. Judging by the way he talks, I bet he used to be a boss.”

I hurried home to find a man exactly as Number 3 had described. Showing me a piece of paper with my address on it, he said that his son, Xiao Zhao, had written and asked him to come and request the favour. He knew his son had said nothing to me.

On the day I arrived back at the farm, Xiao Zhao came to my dorm to pick up his package. He apologized for not asking me ahead of time for the favour. I was confused and too shy to ask him where he had acquired my address.

One day the following spring when I came back from the paddies for lunch, Xiao Zhao met me at my dorm.

“Do you have any fresh water?” he asked. “The pump is not working.”

From then on, he would visit our dorm a couple of nights each week. Many of the girls were happy to see him. He would say “Hello, everyone!” and be entertained by hopeful females, plied with cookies and tea. But gradually he spent more and more time talking to me, and it soon became clear that I was the one he had come to visit.

For the first time, I had someone to talk to. Tentatively, Xiao Zhao asked me about my house arrest, but I gave him no details. I was still ashamed of myself and had decided to take my shame to the grave. Most people didn’t want to relive those days. “Look to the future,” they would say, “there’s no use refrying old rice.” Nevertheless, I was thankful for his concern.

Xiao Zhao was a kind and sympathetic listener, and our talks were the start of our relationship. I was flattered that he had chosen me when so many women were attracted to him, but at first I was reluctant to begin dating him, and said so.

“Is it because you haven’t written back to your pal Xiao Qian yet?”

“How did you know about that?”

He laughed. “Oh, I have friends in the post office.”

He kept our relationship from his family. He was worried that his parents, especially his father, would reject it. Boss Zhao, a strict traditional Chinese father whose authority extended to every aspect of his children’s lives, especially their choice of partner, had insisted that Xiao Zhao not involve himself in any relationship until he left the farm. That was why Xiao Zhao had resisted all the women who would have loved to be his girlfriend.

“It was you I was interested in,” he told me, “ever since I saw you the first time.”

“Why did you wait so long to let me know?”

“Well,” he answered, “you always seemed to be in trouble of one kind or another.”

Although it was not the answer I wanted to hear, I accepted it. At least he was frank with me.

I didn’t tell anyone in my family about him, either. I didn’t know how long our relationship would last; most of those on the farm were short-lived. Besides, I didn’t want another reason for Great-Aunt to get stirred up.

On the day I took my exam, Xiao Zhao came to see me in the evening. We sat outside the dorm, as usual. I was utterly exhausted, but peaceful. Xiao Zhao was unusually quiet. Finally he spoke.

“Tell me. Will you drop me like a sack of potatoes if you get into university?”

“Of course not!” I answered. “Why are you talking about this? You shouldn’t. It’s bad luck to talk about events in advance.” Great-Aunt’s superstitions had had an effect on me and I thought for a moment he was trying to put a curse on my chance by predicting success before the results were known. I hoped my quick response would make him drop the subject.

But he ignored me. “You are going to be a student at Bei Da”—the short form for Beijing University—“one of the best in China. And I probably will stay here for the rest of my life, being a peasant.” He emphasized the last word, although strictly speaking he was not a peasant; he did not work in the fields.

“Just drop it,” I said. “I don’t want to talk about it any more. We can discuss it when the time comes.”

“No,” he insisted again. “It will be too late then. I want you to promise now, tonight. Will you abandon me or not?”

“You’ve got your answer.” I got up and went inside the dorm.

I didn’t sleep that night. With no preparation, suddenly Xiao Zhao had forced me to make a serious commitment. I had often heard the heartbroken sobbing of those who had been abandoned by their “city

hu-kou”

boyfriends and had joined in condemning their unfaithfulness. It became clear to me that I would have no option if I was accepted at Bei Da, at least if Xiao Zhao was still on the farm. Duty would now prohibit me from breaking off with him.

It was ten long days later that the news came. I was in my dorm after the day’s work, fetching my food tin, when Sun knocked on the door and stepped inside.

“Xiao Ye. I just got a phone call.”

My tin dropped from my hands, my throat went dry and

my

temples pounded. “What did they say?”

A smile broke across Sun’s narrow face. “You’ve been accepted. Go to the sub-farm tomorrow and fill out the enrollment forms.”

My hands began to shake. Soon my whole body was trembling and I had to sit down. I laid my head on the table and covered it with my arms. I was going to be a university student. Suddenly, unbelievably, a bright ray of sunshine lit up my future. I wished my parents could know, and, thinking of them, I began to weep quietly. Now Great-Aunt could be proud of me. Now the burden of guilt at my replacing her on the farm would lift itself from Number 3’s shoulders. Now I could help my little sister.

“Congratulations, Xiao Ye,” Sun said, pulling the door closed as he left.

The word spread quickly and I was showered with good wishes. I was the first ever in our brigade to go to university since we had arrived here six years before. The next morning, after a night without rest, I went to the sub-farm office. My hand shook as I filled out the enrollment paper with my name on it.

I learned that my acceptance notice had been sitting in a desk drawer since my exams took place, but no one had bothered to tell me.

It was difficult to grasp the fact that my days as a peasant labourer in the unyielding paddies were over. Except for Xiao Zhao and a few supportive friends, I had no one to say goodbye to. Certainly I would not miss the stark, unfriendly

landscape or the northwest wind. I remembered poor Jia-ying. Soon after her transfer to the vegetable-growing team, her brother had come to visit her and the two of them spent the afternoon together in the dorm with no others around, causing some women to gossip behind her back and men to laugh at her in front of her face, accusing her of incest. The shame and humiliation drove her to mental instability and she was sent back to Shanghai. I remembered my four “counterrevolutionary” friends and the ordeal that shattered our unity; the days of unearned ostracism and disgrace; the struggle meetings; and always, the thousands of hours of backbreaking labour.

I had entered my twenty-third year. Up till now my existence had been controlled by fate, political storm, and loss. Maybe now I could lay my hand on the rudder of my own life and steer out of the bitter sea.

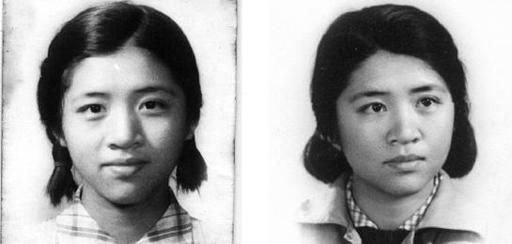

(Left) my ID photo for the prison farm where I laboured for six years (1968–74) and was persecuted as a “counterrevolutionary.”

(Right) My Beijing University ID photo, autumn 1974

.

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR