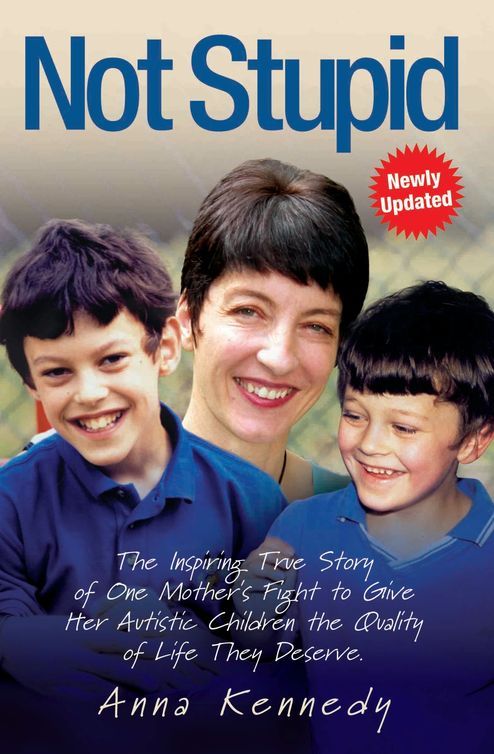

Not Stupid

Authors: Anna Kennedy

I would like to dedicate this book to my sons Patrick and Angelo, since they have taught me anything is possible and they have given me the strength to make a difference.

I have learned a lot from you, Sean, and have achieved more than I thought I was capable of, because you were by my side. Thank you.

Has this ever happened to you?

Not getting a joke?

Feeling left out?

Not knowing what to say?

Saying the wrong thing?

Not being able to concentrate?

Interrupting someone?

Making a mistake?

Feeling confused?

Feeling frightened?

Being told off but you don’t know why?

Not understanding something?

Doing your best but still getting it wrong?

Imagine this happening to you every day. This is what it can be like for children with Asperger Syndrome and autism.

I

used to take as my proverb the warning by Edmund Burke, ‘For evil to triumph it is only necessary that good men do nothing’. But that was in my youth, and the young are inclined to be pessimistic.

Now in my maturity – as we old people call our sixth decade – I prefer to turn that saying upside down: ‘For goodness to win through,’ I say, ‘it is only necessary that a good woman does something’ – and you can’t get a bigger, better example of that kind of victory than Anna Kennedy’s story.

What a woman! Sometimes when you watch great athletes leaping over a hurdle you wonder if they really understand how high it is, how many ordinary mortals would give up at the sight of it, or crack their shins painfully at the first attempt, and never try again.

Anna has leapt over hurdles most of us would run from, barriers so high that you wonder how it is that she’s not totally worn out. She is a slender, pretty brunette who doesn’t

look like an Olympic athlete, but then among her other huge talents Anna is a dancer, and dancers have a very special energy and grace.

She has needed those skills. To create the school her own sons, Angelo and Patrick, and hundreds of other autistic children in Hillingdon urgently needed, Anna begged, borrowed, persuaded and cajoled individuals, local councillors, companies, charities and the media.

She’s not a rich woman; she’s not a politician – all she originally had on her side were her two sons to inspire her, and her husband Sean to stand alongside her. But she is so eloquent, so committed, and her passion is so infectious that she soon attracted a powerful group of disciples who offered their skills and their money to make her dream a reality, and she attracted a terrific team to provide the skills and expertise she needed.

She didn’t want much. Just an appropriate education for her sons, and for half a million other autistic children in Britain. And yet, given the fashion for inclusive education that all too often is an excuse for stinginess and neglect, and denies disabled children the care and attention they need, appropriate education is heartbreakingly difficult to find.

Special-needs schools have been brutally phased out, instead of being expanded and developed, and, in many places, as the Children’s Commissioner has pointed out, for autistic children such schools simply don’t exist. But now in Hillingdon there is the one that Anna and her team created: Hillingdon Manor, with its glowing Ofsted report, its waiting list, and, alongside it, pioneering provision they have created for older autistic students. Because, as with all parents of disabled children,

Anna’s greatest fear is what will happen to them when she is no longer there to fight for them.

Where does Anna get her vision, and the strength to make it a reality? The answers are here in this book. I met Anna only when she was well on the way to creating her school as I was making a television programme about her. Reading about her teenage years, I am eternally grateful to her Italian father, who tried and failed to control her, to stop her going to college, and marrying the man she loved. Winning those early battles and proving she was right must have given Anna the confidence to believe that she could win other, tougher battles.

She and Sean persuaded Hillingdon Council to let her have disused school premises, and Barclays Bank to lend her the money she needed, and an army of volunteers to turn it into an attractive practical school. That was just the beginning, but all the while she was dealing with the dramas and dilemmas in her own family life, for autistic children have a different kind of logic, one that often sets them at odds with the rest of the world.

So there are plenty of moments in this book when you can laugh with Anna, while you are consumed with admiration for her stamina and resourcefulness. How would you like to be stuck on a motorway in the freezing fog in a broken-down car, with a mobile phone that has no signal, and two autistic children? She coped without panicking, just as she coped with all the other ordeals in her life.

This is not a textbook on how to bring up disabled children, nor the best way to teach them, or a toolkit you can use to set up your own school, although I’m sure many parents and

communities will use it that way, because there is plenty of useful information for others who want to follow where she has led.

This is not a personal story of victory, either – Anna is far too modest to see it in those terms – but it is a remarkable testament to the fact that one woman can make a difference, if that woman is Anna Kennedy.

So let me rephrase my proverb again: ‘For goodness to triumph, it is only necessary to have Anna Kennedy on your side’.

T

hankfully, the vast majority of families rarely need to trouble themselves with thoughts of coping day by day with the complex needs of loved ones whose lives have been blighted by either physical or mental conditions. That’s not to say these families go through life without any problems but, when you compare their lives with those who find each day and night a battle to get through, few of them really take the time to fully appreciate their good fortune. I count myself among that number. In fact, until I was invited to help write this book, I had little awareness of how devastating living with autism in its various forms could be.

The chances are, however, that, by picking up this book, you have been touched in some way by the condition. You may be a parent, relative or friend of someone diagnosed with autism or someone coping with it as a carer. Alternatively, you could be someone in the world of the teaching or caring professions whose contact with autism may be limited but you have a need

to find out more about the condition in order to gain a better understanding of how to deal with it within your own field. Or, of course, you may be a person with autism yourself.

Whatever your reason for picking up this book, I truly hope it will enlighten you in the same way as Anna’s story has enlightened me. Anna, I know, does not want to be put on a pedestal for what she has achieved, but it’s so hard not to place her there, for she is a remarkable woman.

Faced with the challenge of finding appropriate educational provision for her two boys, Anna, and her husband Sean, decided upon a course of action that most people would never have contemplated: founding a specialist school dedicated to the care and education of young people with various forms of autism. It was a mammoth task that, on the face of it, was one of folly – but how they have proved everyone wrong!

There are several good reasons for writing

Not Stupid

. From a human-interest point of view, it is a remarkable story of a couple’s love and dedication for their children and their determination to provide them with as good a chance of a happy and productive life as other, more fortunate youngsters.

On the other hand, their story highlights the barriers and misunderstandings placed in their path towards that goal by those who were either too ignorant or too inflexible in their ways to appreciate fully the scale of the problems faced by so many in society when it comes to autism.

Not

Stupid

highlights the depths of despair Anna and Sean endured in their quest to help their boys, and the boys’ torment, which, particularly in their time in nursery and mainstream education, saw them subjected to ridicule and bullying.

That said, this is a story of hope. Anna and Sean have proved that mountains can be moved if you have the determination to focus on your goals, and that living with autism can be made easier when it is more fully and widely understood.

I trust this book will, in some small way, help towards that end.

L

ooking at the psychotherapist’s report, I felt a rush of blood from my feet going straight to my head. ‘It says here my son’s got Asperger Syndrome.’

‘That’s right, Mrs Kennedy.’

‘Well, this report says it was diagnosed three years ago – this is the first time we’ve heard anything about it!’ I was incredulous. How could this total lack of communication over such a vital diagnosis possibly have happened?

Ever since his traumatic birth, our son Patrick had endured poor health, and his experience of life in his nursery school and, later, in a mainstream school had resulted in copious tears and frantic tantrums since day one. Now at last we knew why.

‘Why didn’t anyone tell us this before?’ I demanded.

‘We just assumed you knew.’

My husband Sean and I were attending an annual review at Patrick’s school in 1997, in Hillingdon, northwest London, to discuss his progress – or, should I say, his significant lack of it.

The head teacher, Patrick’s teachers and the educational psychologist present at the meeting didn’t know what to say to us when they realised no one had had the foresight to inform us of Patrick’s condition.

To be honest, the rest of the meeting was just a blur and I was unable to concentrate on anything being discussed because I was selfishly thinking, Christ, both my boys have autism! This is terrible. What have I done wrong?

When we arrived home from the school it soon became obvious that Sean was reluctant to talk about Patrick’s condition at all. Instead he preferred to discuss ways to get back litigiously at the doctor for failing to inform us when Patrick had been originally diagnosed.

All this was in the wake of learning, shortly earlier, that our younger son, Angelo, had autism. At the time we had known nothing of the condition. If I remember correctly, my first instinct was to wonder how long Angelo would live and I had immersed myself in a quest to find out as much as possible about the condition, with varying degrees of success, ever since. At least the literature I had recently read had given me some idea of what Asperger Syndrome was.

Nevertheless, the news that Patrick had it made me realise that my dreams of one day having children of my own and a carefree life were turning out to be a far cry from what I had hoped. Because my own childhood had been so regimented, I had been looking forward to a more relaxed way of life when, eventually, I would settle down and have a family of my own. I’d had dreams of days on the beach with my kids building sandcastles and having fun. Now all those aspirations seemed like a distant memory.

I decided to speak to the consultant paediatrician at Hillingdon Hospital to find out why we had not been informed of Patrick’s diagnosis three years earlier. The paediatrician insisted he had, indeed, informed us of his diagnosis at the time. ‘I think we would have remembered something like that if you had,’ I replied angrily.

My only recollection of that particular meeting in 1994 was that the paediatrician had said, ‘Your son has got very difficult behaviour’ – and that he had recommended we send him away to a residential school, but there was no way Sean and I would even have considered that, particularly as Patrick was only 4 years old at the time.

Sean and I now found ourselves setting out on a new path in life that would, over the following years, see us embroiled in a long and drawn-out lobby with the civic and education authorities as we battled to provide our sons with the same rights to an appropriate education and way of life as other, more ‘normal’, children have.

There’s no doubting that a diagnosis of any of the conditions in what is known as the autistic spectrum would plunge any family concerned into a deep sense of crisis – and we were certainly no different. As with most people, our knowledge of autism prior to Angelo’s diagnosis had been practically nonexistent and we can now recognise that what many people can see only as a naughty child can be anything but the case. We had now entered a world where only those directly affected can truly appreciate the difficulties and barriers that need to be overcome.

Autism, we discovered, affects around 520,000 people in Britain. The condition, a brain disorder that impairs the ability

to relate and communicate, is unrelated to intelligence. In fact, the autistic spectrum includes both highly intelligent individuals and others with severe learning needs. People with autism face difficulties in interacting socially. They have poor concentration and, in some cases, can display disruptive behaviour, which many observers unfamiliar with the condition often put down to naughtiness. Hopefully, this book will go some way to explaining what autism is all about, will reassure parents of children recently diagnosed with the condition, and hopefully, educate those who do not fully understand all the difficulties faced by sufferers and their carers.

There are several instances in my past that have had a profound bearing on my personality and that have shaped me into the type of person I am today. At the very least, the following few pages will illustrate why, to me, barriers are there only to be broken down.

It was back in 1984 that I first met my husband Sean. It was not long after my family had moved back to Middlesbrough from Italy – an unplanned return following the destruction of my parents’ home by an earthquake in Monte Cassino.

The earthquake had been an extremely frightening experience. My mother had just persuaded me, a teetotaller, to try a glass of Cinzano. As I sipped it, the walls shook and saucepans and pots began falling onto the floor. My sister Maria Luisa began screaming, then jumped on top of me and flung her arms around my neck in blind panic. I could hardly breathe. Mum prised her off me and we all hurried down the stairs as they were splitting apart under our feet.

As our home shook even more violently and began to disintegrate, we rushed outside into the piazza. During a smaller, subsequent earthquake, I saw the nearby church become badly damaged and saw mannequins crashing through the windows of the shops.

I was 24 years old when we returned to the northeast of England. Given the chance, I would have loved to remain in Italy to continue running the successful dance school, Scuola de Danza de Anna, that I had set up on our arrival in Monte Cassino three years earlier, but my father, who is Italian, was having none of it. As far as he was concerned, the family – my mother, brother Tullio, Maria Luisa and I – would all return to Britain straightaway. I was gutted. My dance school had taken off really well and had the added selling point that I spoke English, so the kids coming to classes could improve their language skills at the same time.

Back in Middlesbrough, when I was 25, I found work in the office of the Whinney Banks Community Centre during the daytime and worked teaching dance to teenagers with special needs at the centre in the evenings.

One evening, as he rushed into the building, I noticed a young man wearing a Crombie coat, green socks and Dunlop trainers. He had what I would describe as a Jackson Five fuzzy haircut and a thick, bushy beard. He ran through the building and dashed up the stairs three or four at a time to where the yoga classes were being held.

He returned the next day as I was sitting in the lounge area during my lunch break. I must have been sitting very upright in my chair when Sean approached me. ‘Have you got a rod up

your back?’ he asked. I just looked at him. What a strange guy! He sat down and stroked his beard.

‘Do you like beards?’

‘No,’ I replied as I turned my head away and ignored him.

‘OK,’ he said as he got up and off he went.

He was back again the following day, minus his beard. He looked at me and was obviously waiting for me to say something, but I didn’t. Then he started chatting to me. I have to admit, I really liked his eyes and the soft tone of his voice, which was surprising coming from such a big chap, who turned out to be a former rugby player – Sean was around six-

foot-four

tall and weighed around 18 stone.

After a while I got up to leave. I needed to be at Kirby College to attend a dance class to learn a new routine that I’d never tried before. Sean asked if he could walk me there and, on the way, he asked me for a date. I declined, concerned about what my father would say – even when I was 25 years old, my father strongly disapproved of me dating; the same went for my sister. Dad was so strict that if I was watching a film featuring a scene with a couple kissing I would be told to turn my head away. I was still doing so at 18 years of age because I’d been so conditioned by him. How crazy is that!

As a child, I hadn’t been allowed to go to friends’ houses to play. I’d been living such a sheltered life. From the ages of 13 to 16, I attended a convent school, where I took GCE O-levels and CSEs (Certificate of Secondary Education, which preceded the General Certificate of Secondary Education, or GCSE, in the UK) in French, English, needlework, domestic science, religious scriptures, maths and Italian. At the time I was incredibly naïve.

After leaving school, I had, at the age of 16, my first experience of death and feelings of loss and despair when my friend Karen, who was also 16, died from a brain tumour. I found her death very hard to handle and to come to terms with.

I never dated at all until I was in my early twenties. When it came to boyfriends I’d had to be sneaky in case Dad found out. I had to pretend I was going to run an errand for my mother in order to get out of the house because Dad had such a controlling influence on us all. I think he was scared that my sister and I would be taken advantage of.

On leaving school at 16 I had wanted to enrol at Kirby College in order to learn to become an interpreter, but Dad had ripped up my application form. ‘Good girls stay at home,’ he’d insisted. When I was 17 my mother had a word with Dad. She told him I shouldn’t be hanging around at home all day. If I didn’t go to college he should let me go out to work. He reluctantly agreed and, after an interview at the Binns department store, I was taken on in the lingerie department, which necessitated my attending Kirby College one day a week to undertake business studies, so I did get there in the end.

My only escape from such regimented order came in the form of dance. When I was a young child, my mother had taken me to the Mavis Percival Dance School and it was there that I felt truly free to express myself. In a way, I was like a free bird when I danced – even though Dad tried several times to stop me going. As I’d grown up I’d enjoyed preparing for dance competitions and shows. I loved tap dancing but I also had to do ballet, which, to be honest, I hated. I much preferred

fast-tapping

jazz routines – ones you had to attack. I’m not a

smoothy, floaty person. That’s just not me. But the ballet was a necessity if I was to improve my posture.

After working at Binns for 18 months I decided to open my own dance school. I’d studied for my teaching qualifications and was pleased to pass with 96 points from a possible 100. After helping my own dance teacher for a while, I began taking classes of my own in a church hall in Middlesbrough. At one time I had a hundred pupils. It was a very satisfying experience but, after I’d worked at Binns all day, dancing in the evenings meant I was always knackered! I had to choose between Binns and dance classes – so I chose the dancing.

It was only natural, bearing in mind Dad’s strict manner, that, when Sean asked me out for a date, my main concern was of Dad’s reaction, should he find out. But, when I declined Sean’s offer, he refused to give up, even when I explained my reasons why. Sean told me he would meet me in the nearby Debenham’s store and that I could use the excuse of running an errand for my mother as an excuse to get away.

It was absolutely pelting down with rain as I made my way to Debenham’s. I was convinced Sean wouldn’t be there, but there he was, wearing a smart suit and holding an umbrella. I was nervous. Although I’d already secretly seen a few boys in the short term, my first date with Sean was in the wake of a bad experience with one boy that had really scared me, mainly because I had been so naïve at the time. Sean, on the other hand, was quite forward and not shy at all. After chatting, we were surprised to find out that we had attended the same school in Middlesbrough and at the same time, although, to the best of our knowledge, we had never met.

Within three weeks Sean had asked me to marry him. At the time, we were in the house he shared with his mother, Coral, and his Aunt Pam. Sean had even cooked the meal for the occasion. A week later he took me into the town because he wanted to buy me a ring. It was now time to break the news to my family, but, when we got home, we discovered that Maria Luisa had been rushed to hospital with appendicitis, so it was obviously not the most appropriate of times to share our news. Instead I went straight to the hospital to see her.

However, the time eventually came when Sean was to be introduced to Dad. It was a complete nightmare. Everyone was nervous and Mum was baking for England. I’d already primed Sean to say all the things I thought Dad would want to hear, but it very soon became obvious that Sean was his own man. No one was going to tell him what he could or couldn’t say!

I was cringing as Dad became angrier and angrier. There were long silences, interrupted only by Mum frequently asking if anyone wanted more strawberry cakes. The meeting was a disaster. Dad was completely unimpressed, declaring, ‘He’s not going out with my daughter!’ Consequently, further meetings between Sean and me had to be clandestine.

I was heartbroken when Sean left Middlesbrough to attend Brunel University in Uxbridge, northwest London – and so was he. On arrival in London he rang me to say he’d get the first bus home to be with me again, but I persuaded him to stay. After four or five days, however, I was missing him so much. My Aunt Anita could see how low I was and said I should just pack up some things and go to him, that at my age I shouldn’t still be under Dad’s wing. Although I only had around

£

20 on me,

I took the train to King’s Cross, where Sean was waiting for me on the platform. It was so good to see him again.