Notebooks (55 page)

Authors: Leonardo da Vinci,Irma Anne Richter,Thereza Wells

Tags: #History, #Fiction, #General, #European, #Art, #Renaissance, #Leonardo;, #Leonardo, #da Vinci;, #1452-1519, #Individual artists, #Art Monographs, #Drawing By Individual Artists, #Notebooks; sketchbooks; etc, #Individual Artist, #History - Renaissance, #Renaissance art, #Individual Painters - Renaissance, #Drawing & drawings, #Drawing, #Techniques - Drawing, #Individual Artists - General, #Individual artists; art monographs, #Art & Art Instruction, #Techniques

Meanwhile he studied the topography and made maps of the district for military purposes.

From Bonconvento to Casanova 10 miles; from Casanova to Chiusi 9 miles, from Chiusi to Perugia 12 miles; from Perugia to Santa Maria degli Angeli and then to Foligno.

95

95

Leonardo’s method of procedure in drawing maps was first to chart the river systems and determine the locality of the towns and then around these watersheds insert the mountains. The result was very suggestive of the nature of the terrain. The following note refers to map drawing.

On the tops of the sides of the hills foreshorten the shape of the ground and its division, but give its proper shape to what is turned towards you.

96

96

While studying the watersheds of Chiana and the upper Arno he looked for shells in order to ascertain whether these parts had been submerged by the sea in former ages.

Where the valleys have never been covered by the salt water of the sea there shells are never found; as is plainly visible in the great valley of the Arno above Gonfolina, a rock which was once united with Monte Albano in the form of a very high bank. This kept the river dammed up in such a way that before it could flow into the sea which was then at the foot of this rock, it formed two large lakes, the first of which was where we now see the flourishing city of Florence together with Prato and Pistoia. . . . In the upper part of the Val d’Arno, as far as Arezzo, a second lake was formed which discharged its waters into the above-mentioned lake. It was shut in at about where now we see Girone, and it filled all the valley above for a distance of forty miles. This valley received upon its base all the soil brought down by the turbid waters and it is still to be seen at its maximum height at the foot of Prato Magno for there the rivers have not worn it away.

Across this land may be seen the deep cuts of the rivers which have passed there in their descent from the great mountain of Prato Magno; in which cuts there are no traces of any shells or of marine soil This lake was joined to that of Perugia.

97

97

Pigeon House at Urbino. 30 July 1502

98

98

Passing through Urbino Leonardo saw the magnificent Renaissance castle built for Federico da Montefeltro, duke of Urbino. It had been a renowned centre of art and literature. Now young Guidobaldo, Federico’s son and heir, had fled from his home.

The fortress of Urbino.

99

99

The following note in the same notebook was probably suggested by the pillage of the palace whose treasures Cesare Borgia had sent to Cesena.

Of mules which have on them rich burdens of silver and gold. Much treasure and great riches will be laid upon four-footed beasts which will convey them to divers places.

100

100

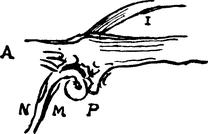

In ascending the staircase of the pillaged palace Leonardo made a hasty sketch of the columned arches on one of the landings.

Another sketch illustrates the unsatisfactory effect of a plinth which is narrower than the wall

.

.

Steps of Urbino.

The plinth must be as broad as the thickness of the wall against which the plinth is built.

101

101

First day of August 1502. At Pesaro, the Library.

87

87

There is harmony in the different falls of water as you saw at the fountain of Rimini on 8th day of August 1502.

102

102

The shepherds in the Romagna at the foot of the Apennines make peculiar large cavities in the mountains in the form of a horn, and on one side they fasten a horn. This little horn becomes one and the same with the said cavity and thus they produce a very loud sound by blowing into it.

103

103

In Romagna, the realm of all the dullards, they use carts with four equal wheels, or they have two low in front and two high ones behind and this is a great restraint on movement because more weight is resting upon the front wheels than upon those behind, as I have shown.

. . . And these first wheels move less easily than the large ones, so that to increase the weight in front is to diminish the power of movement and so to double the difficulty.

[

With a drawing

.]

With a drawing

.]

Here the larger wheel has three times the leverage of the small wheel; consequently the small one finds three times as much resistance and to add a hundred pounds [necessitates adding] two hundred more to the small [wheel].

104

104

[

With drawing of castle.

]

With drawing of castle.

]

St Mary’s Day, the middle of August at Cesena 1502.

105

105

[

With a sketch of two bunches of grapes hanging on a hook

.]

With a sketch of two bunches of grapes hanging on a hook

.]

Thus grapes are carried at Cesena.

106

106

A visit to Cesare Borgia by a delegation from the sultan Baiazeth possibly revived Leonardo’s interest in the East. The sultan was planning the construction of a bridge between Pera and Constantinople to replace a wooden structure resting on heavy barges that had been thrown across the Golden Horn.

Leonardo drew a plan for the bridge in his notebook.

Bridge from Pera to Constantinople.

40 ells wide, 70 ells above water, and 600 ells long, 400 ells being above the water and 200 resting on land. In this way it provides its own supports.

107

107

On 18 August 1502 Cesare Borgia while conferring at Pavia with the French king appointed Leonardo his chief engineer. He was to supervise the fortresses in the conquered provinces and was given power to requisition whatever was needed.

[

With a drawing.

]

With a drawing.

]

At Porto Cesenatico on the 6th of September 1502 at the 15th hour. How the bastions should project beyond the walls of towns to defend the outer slopes, so that they may not be struck by artillery.

107

107

On returning to Romagna Cesare Borgia found himself isolated at Imola, his captains conspiring against him, and Urbino in revolt. Leonardo’s plan of Imola, with indications of the distances to places in the neighbourhood, dates from about this time. Florence supported the cause of Cesare and sent Niccolò Machiavelli with offers of help. Both he and Leonardo were now able to observe the course of events which culminated in Cesare murdering his disaffected captains as they met him in order to be reconciled, on 12 December 1502. Among the victims was Vitellozzo Vitegli (see p. 320). The campaign was over and Cesare left for Rome in February 1503.

In

The Prince

(Il Principe) Machiavelli gave his ideal statesman the name of Valentino after Cesare Borgia, the duke of Valentino. In the following note Leonardo also refers to him by that name.

The Prince

(Il Principe) Machiavelli gave his ideal statesman the name of Valentino after Cesare Borgia, the duke of Valentino. In the following note Leonardo also refers to him by that name.

Where is Valentino?

Boots, boxes in the customhouse, the monk at Carmine, squares.

Piero Martelli.

Salvi Borghesini.

return the bags.

a support for the spectacles.

the nude of Sangallo.

the cloak. . . .

108

108

In February 1503 Leonardo may have ended his service to Cesare Borgia and returned to Florence.

Memorandum. That on the eighth day of April 1503 I, Leonardo da Vinci, lent to Vante, the miniature painter, four gold ducats. Salaì carried them to him and gave them into his own hand, and he said he would repay them within the space of forty days.

Memorandum. How on the same day I paid to Salaì three gold ducats which he said he wanted for a pair of rose-coloured hose with their trimming. And there remain nine ducats due to him—excepting that he owes me twenty ducats; seventeen I lent him at Milan and three at Venice.

109

109

This old man, a few hours before his death told me that he had lived a hundred years, and that he did not feel any bodily ailment other than weakness, and thus while sitting on a bed in the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova at Florence without moving or sign of anything amiss, he passed from this life. And I examined the anatomy to ascertain the cause of so sweet a death, and found that it was caused by weakness through failure of blood and of the artery that feeds the heart and the lower members which I found to be very parched and shrunk and withered; and the result of this examination I wrote down very carefully. . . . The other autopsy was on a child of two years old, and here I found everything the contrary to what was the case in the old man . . . .

110

110

[

With a drawing

.]

With a drawing

.]

This is the reverse of the tongue, and its surface is rough in many animals and especially in the leonine species, such as lions, panthers, leopards, lynxes, cats and the like which have the surface of their tongues very rough as though covered with minute somewhat flexible nails; and when they lick their skin these nails penetrate to the root of the hairs, and act like combs in removing the small animals which feed upon them.

And I once saw how a lamb was licked by a lion in our city of Florence, where there are always twenty-five to thirty of them, and they bear young. The lion with a few strokes of his tongue stripped off the whole fleece of the lamb, and after having made it bare, ate it.

111

111

June and July 1503. During the siege of Pisa, Leonardo stays in Pisa’s Camposanto and makes topographical sketches and designs for military machines and fortifications for the Signoria of Florence.

On 24 July he visited the camp of the Florentine army besieging Pisa and approved of a plan to straighten the river so as to deprive Pisa of its water and make Florence directly accessible from the sea. The plan had the support of his friend Machiavelli, and if feasible would end the war between Florence and Pisa which had been dragging on for years. The report from the camp says: ‘Yesterday came here accompanied by one of the Signoria, Alessandro degli Albizzi with Leonardo da Vinci and others and after seeing the plan and after many discussions and doubts it was decided that the undertaking would be very much to the purpose. . . .’ The expense of this visit was borne by the State and comprised the use of carriages and six horses.

Leonardo drew maps of the lower course of the Arno and work was begun in August 1504. He had previously acquired a thorough knowledge of the upper river course at Arezzo (see p. 321) and was therefore able to visualize its history. He combined his engineering with geological investigations.

Underground, and under the foundation of buildings, timbers are found of wrought beams already black. Such were found in my time in those diggings at Castel Fiorentino. And these had been in that place before the sand carried by the Arno into the sea had been raised to such a height; and before the plains of Casentino had been so much lowered by the action of the Arno in constantly carrying down earth from there.

26

26

They do not know why the Arno never keeps its channel. It is because the rivers which flow into it deposit soil where they enter and wear it away from the other side bending the river there. . . .

112

112

The eddy made by the Mensola when the Arno is low and the Mensola full.

113

113

The work, started in August 1504, was abandoned in October. But Leonardo’s mind continued to dwell on the problem. A year later on meeting the Florentine engraver and medallist Niccolò di Forzore Spinelli, he noted down his account of methods of canalization adopted in Flanders.

That a river which is to be turned from one place to another must be coaxed and not treated roughly or with violence; and to do this a sort of dam should be built into the river, and then lower down another one projecting further and in like manner a third, fourth, and fifth so that the river may discharge itself into the channel allotted to it, or by this means it may be diverted from the place it has damaged as was done in Flanders according to what I was told by Niccolò di Forzore.*

Other books

Scott Pilgrim 03 by Scott Pilgrim, The Infinite Sadness (2006)

Serena's Choice - Coastal Romance Series by Ransom, Jennifer

Gray Girl by Susan I. Spieth

TAKEN BY THE CEO (Dominated by my BDSM BOSS) by FOXX, FIONA

My Masters' Nightmare, Season 1 / Episode 13 by Marita A. Hansen

Highland Sparks (Clan Grant #5) by Keira Montclair

Double Dealing: A Menage Romance by Landish, Lauren

Blanco County 04 - Guilt Trip by Rehder, Ben

Samurai and Other Stories by William Meikle

Finding His Dragon (Dragon Blood Book 3) by Adams, Elianne