Notebooks (51 page)

Authors: Leonardo da Vinci,Irma Anne Richter,Thereza Wells

Tags: #History, #Fiction, #General, #European, #Art, #Renaissance, #Leonardo;, #Leonardo, #da Vinci;, #1452-1519, #Individual artists, #Art Monographs, #Drawing By Individual Artists, #Notebooks; sketchbooks; etc, #Individual Artist, #History - Renaissance, #Renaissance art, #Individual Painters - Renaissance, #Drawing & drawings, #Drawing, #Techniques - Drawing, #Individual Artists - General, #Individual artists; art monographs, #Art & Art Instruction, #Techniques

Stair of Vigevano below the Sforzesca, 130 steps, ½ braccio high and ½ braccio wide, down which the water falls, so as not to wear anything at the end of its fall; by these steps so much soil has come down that it has dried up a pool; that is to say, it has filled it up and a pool of great depth has been turned into meadows.

41

41

Vineyards of Vigevano. On the 20th day of March 1494. And in the winter they are covered with earth.

42

42

Below this note is a sketch showing the alignment of plants in these vineyards, which is much the same as that prevailing at Vigevano and other Lombard vineyards today, but differs from Tuscan vineyards where the winter is not so severe. Leonardo remembered his young days in the country in Tuscany and observed the difference.

On the 23rd day of August 12 lire from Pulisona.

On the 14th of March 1494 Galeazzo came to live with me, agreeing to pay 5 lire a month for his cost, and paying on the 14th day of each month.

His father gave me 2 Rhenish florins.

On the 14th of July I had from Galeazzo 2 Rhenish florins.

43

43

On the 15th day of September Giulio began the lock of my studio, 1494.

44

44

In September 1494 Charles VIII of France entered Lombardy with an army on his way to the kingdom of Naples. He was received as an ally by Ludovico Sforza and entertained at Pavia. Meanwhile the duke of Orléans, afterwards Louis XII, who commanded the vanguard of the royal army, occupied Genoa and was menacing Milan. He was already dreaming of asserting his rights on this city based on the marriage of his grandfather with a Visconti.

On 21 October 1494 the young duke of Milan, Gian Galeazzo, died at Pavia. The manner of his death gave rise to suspicions that poison had been administered by order of his uncle Ludovico. On the following day, at the Castello Sforzesco at Milan, Ludovico was proclaimed duke, superseding Gian Galeazzo’s infant son, in order to provide an adult male during these troubled times.

On 17 November 1494, under the pressure of political events, Duke Ludovico shipped the bronze intended for casting Leonardo’s model of a horse down the Po to Ferrara to be made into cannon.

In the notebooks used by Leonardo at this time we find the following somewhat obscure entries referring to allegorical representations in connection with the two dukes.

Il Moro [Ludovico Sforza] with spectacles,

and Envy depicted with False report,

and Justice black for il Moro.

45

45

Ermine with mud.

Galeazzo between calm weather and flight of fortune.

46

46

The ermine will die rather than besmirch itself.

47

47

In the same notebook are a series of transcriptions from a popular medieval bestiary (see p. 215). These were probably made in connection with recitations and performances at court.

On Tuesday I bought wine for the morning, on Friday the 4th day of September (1495) the same.

48

48

The little notebook which is dated by this entry of the purchase of wine deals mainly with mechanics.

Double floor.

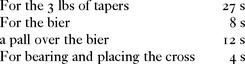

Funeral expenses of Caterina

51

51

Caterina had entered his household in 1493 and had therefore been with him for a few years.

She may have died in hospital, since Leonardo wrote the following note on the next page of the same notebook. It has been suggested that this housekeeper was his mother, who bore the same name (see p. 269), but this seems improbable.

Piscin da Mozania at the hospital of Brolio has many veins on arms and legs.

52

52

He was interested in a systematic representation of the veins of the human body as is shown by the following notes on a sheet at Windsor datable about this time.

[

With drawing of figure showing the anatomy of veins.

]

With drawing of figure showing the anatomy of veins.

]

Here shall be represented the tree of the vessels generally, as Ptolemy* did with the universe in his Cosmography; here shall be represented the vessels of each member separately from different aspects.

Draw the view of the ramification of the vessels from behind, from the front and from the side; otherwise you do not give true demonstration of their ramification, shape, and position.

53

53

The pupil in man dilates and contracts according to the brightness or darkness of the object in view; and since it takes some time to dilate and contract it cannot see immediately on going out of the light into the dark, and similarly out of the dark into the light; and this very thing has once deceived me in painting an eye, and from that I learned it.

54

54

In 1495 Leonardo began to work on his painting of the Last Supper on a wall of the refectory of the Dominican friary of Santa Maria delle Grazie. In his notebook are drawings of the plinths in the apsis of that church (see below). The following notes in the same book show how he was looking for models for his figure of Christ.

Christ—The young count, the one with the Cardinal of Mortaro. Giovannina has a fantastic face, lives at Santa Caterina, at the hospital.

55

55

Alessandro Carissimo of Parma, for the hand of Christ.

56

56

Among the apostles represented in the painting are portraits of courtiers and men in Milan. The following description of Leonardo’s methods of studying is of interest in this connection.

Giovanbatista Giraldi, whose father knew Leonardo, wrote: ‘When Leonardo wished to paint a figure he first considered what social standing and what nature it was to represent; whether noble or plebeian, gay or severe, troubled or serene, old or young, irate or quiet, good or evil; and when he had made up his mind, he went to places where he knew that people of that kind assembled and observed their faces, their manners, dresses, and gestures;

and when he found what fitted his purpose, he noted it in a little book which he was always carrying in his belt. After repeating this procedure many times, and being satisfied with the material thus collected for the figure which he wished to paint, he would proceed to give it shape, and he would succeed marvellously.’

and when he found what fitted his purpose, he noted it in a little book which he was always carrying in his belt. After repeating this procedure many times, and being satisfied with the material thus collected for the figure which he wished to paint, he would proceed to give it shape, and he would succeed marvellously.’

Draft of a letter probably from about this time addressed to Piacenza which at that time formed part of the duchy of Milan.

Magnificent Commissioners of Buildings! Hearing that Your Magnificences have resolved to make certain great works in bronze, I will put certain things on record for you. First, that you should not be so quick and hasty in awarding the commission that by your speed you put it out of your power to choose a good model and a good master as Italy has a number of men of capacity. Some man may be chosen who by his insufficiency may afford occasion to your successors to blame you and your age, judging that this age was poorly equipped with men of good judgement or good masters; seeing that other cities and especially the city of the Florentines were almost at this very same time endowed with beautiful and great works in bronze; amongst these being the doors of their baptistery. . . . And this Florence, like Piacenza, is a place of intercourse, through which many foreigners pass; who, when they see that the works are fine and good, form the impression that the city must have worthy inhabitants, seeing that the works serve as evidence of their opinion. And on the contrary, I say, that if they see a great expenditure in metal wrought so poorly, it would be less shame to the city if the doors were of plain wood, because the material costing so little, would not seem to merit any great outlay of skill.

Now the principal parts which are sought for in cities are their cathedrals, and as one approaches these the first things which meet the eye are the doors by which one passes into these churches. Beware, gentlemen of the commission, lest the too great speed in wishing with such haste to expedite the commission of so great a work as that which I hear you have ordered, may become the reason why what was intended for the honour of God and of men may prove a great dishonour to your judgements and to your city, where as it is a place of distinction and resort there is a concourse of innumerable foreigners. And this disgrace would befall you if by your negligence you put your trust in some braggart who, by his tricks or by the favour shown to him, were to be awarded such a commission by you as should bring great and lasting shame to him and to you.

I cannot help feeling angry when I reflect what men those are who have conferred with me wishing to embark on such an undertaking without giving a thought to their capacity for it, not to say more.

One is a maker of pots, another of cuirasses, yet another makes bells and another collars for them, another even is a bombardier. And among them one in his Lordship’s service who boasted that he is an intimate acquaintance of Messer Ambrosio Ferere who has some influence and has made certain promises to him; and if this were not enough he will get on his horse and ride off to his Lord and get such letters from him that you will never refuse him the work. But consider to what straits the poor students who are competent to execute such work are reduced when they have to compete with such men as these.

Other books

Doubletake by Rob Thurman

Quicksilver by Stephanie Spinner

The Flood Girls by Richard Fifield

Wicked Games by A. D. Justice

Halfway Bitten by Terry Maggert

Planet X by Eduard Joseph

2nd: Love for Sale by Michelle Hughes, Liz Borino

Show Time by Sue Stauffacher

Easton's Gold by Paul Butler