On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears (20 page)

Read On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears Online

Authors: Stephen T. Asma

Happily, one’s penis does not go missing, the inquisitor assures us, if one is in a state of grace. The best protection against penis-stealing witches is sexual modesty. Witches cannot infiltrate the righteous man’s “imaginative faculty” in order to play this trick on him.

20

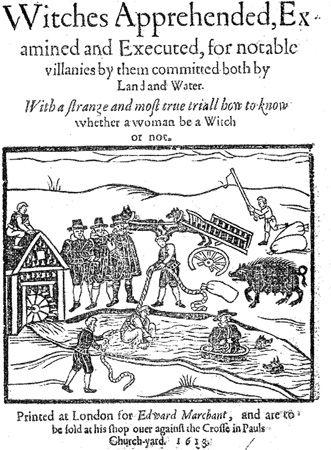

A 1613 pamphlet advertising witch detection tests. A woman is being dunked in water to determine her status. Courtesy of the Newberry Library.

Although it is disheartening to

think

you’ve lost your penis, it’s significantly worse to really lose it. True removal is effected directly by the demons themselves, rather than through the conjuring witches. So how do you know if your penis has really been removed or just whisked away by a witch-induced hallucination? The answer, perhaps unsurprisingly, is that the former case is accompanied by terrible pain, whereas the latter case is accompanied by “depression.” And rest assured that in either case, as with all such harm, God must have given the green light. If one’s penis goes missing, one can feel confident that one deserved it. Likewise, switching to a milder example, if a man experiences erectile dysfunction when he wants to procreate with his wife, then it’s quite likely to be the result of harmful magic. One can’t help but speculate whether this excuse proved credible to the long-suffering wife.

The inquisitors did not confine themselves to men’s deep castration and performance anxieties, but found room to foment other primordial fears and apprehensions as well. It may be a platitude to mention that no greater wellspring of irrational fear and worry exists than the emotions surrounding the subject of one’s own children. When you first become a parent, charged with the greatest responsibility possible, you discover subterranean deposits of emotional vulnerability in yourself that you didn’t know existed. Parents of the medieval era had the inquisitors to help nourish their worst hysterical fears. Besides stealing penises, witches apparently were very interested in stealing babies. Inquisitors claimed, “Midwives who work harmful magic kill fetuses in the womb in different ways, procure a miscarriage, and, when they do not do this, offer newly born children to evil spirits.”

21

There are three ways witches attempt to counter the sacred purpose of procreation. The first, already mentioned, is to render the penis flaccid. The second is to produce a miscarriage or prevent conception altogether. The third is to steal the infant shortly after birth in order to eat it or offer it to an evil spirit. “Those who are indisputably witches are accustomed, against the inclination of human nature—indeed contrary to the temperament of every animal (at least, with the exception of the wolf)—to devour and feast on young children.”

22

The inquisitor of Como, Italy, relates that “a man had lost his child from its cradle and, while he was searching for it, he saw some women who had gathered together during the nighttime, and he came to the conclusion that they were slaughtering a child, drinking its fluid, and then devouring [it].” In response to that event, the inquisitor came down very hard on the local witches, burning over forty-one of them in a single year. One might well ask how all this baby stealing and torturing was possible. The answer is simple: midwives.

Inquisitors took a very dim view of midwifery.

23

No particular compelling reason is given in the text for this hostility. The Dominican inquisitor Heinrich Institoris claimed, however, that penitent witch midwives had confessed to him, doubtless under duress, “No one does more harm to the Catholic faith than midwives. When they don’t kill the children, they take the babies out of the room, as though they are going to do something out of doors, lift them up in the air, and offer them to evil spirits.”

24

Besides midwife witches, evil demons themselves got into the business of human procreation. Remember the discussion of incubi that we encountered in St. Augustine, who somewhat reluctantly agreed to the

possibility

of spirits having sex with human women. A millennium later, according to the inquisitors, the possibility evolved into certainty.

25

Demonic spirits transformed themselves into attractive and alluring men and women

and then seduced human partners into sexual union. A seductive female demon was called a

succubus

(“bottom,” or underneath) and the male, as we’ve already learned, was called an

incubus

(“top,” or above). The succubus was thought to lure a man into her arms, engage him in sex, and then steal his semen after climax. Once the trickster succubus had the precious bodily fluid, she would bring it to an incubus, who would in turn seduce a human woman, only to deposit the stolen semen into her womb.

26

The woman would be impregnated by this demonic insemination process and in time give birth to a doomed child. But the offspring of such a union was not itself a demon nor the child of a demon. It was, properly speaking, the offspring of the man whose semen was originally stolen and the woman in whom the semen was deposited. Something in this unholy process of deception, however, created a child that was more susceptible to demonic manipulation later in life.

The most famous manual for understanding, detecting, and vanquishing witches is the 1486 text

Malleus Maleficarum

(The Hammer of Witches), written by the Dominican inquisitor Heinrich Institoris. This German witch hunter synthesized his own significant experience chasing and persecuting witches, but also set the terms for subsequent generations of pious purifiers. Witches were a particularly odious species of the larger genus of heresy, and the Inquisition was busy at work protecting orthodoxy and the Roman papacy. In a 1484 papal bull,

Summis desiderantes affectibus

, Pope Innocent VIII gave Institoris and fellow witch hunter Jakob Sprenger wide-ranging legal powers to pursue and eradicate witches. The bull was used as a justificational preface for Institoris’s

Malleus Maleficarum

.

A witch must be understood as a human being who has become a pawn in the various schemes of evil demons. An act of

maleficium

, or harmful magic, requires three things: the evil demon who acts as a puppeteer, the puppet human (or animal) who works the harmful magic, and God’s acquiescence. But the puppetry goes both ways: once the human-demon compact has been sworn, the human believes he is manipulating evil spirits to do his bidding. The witch feels like the puppet master… for a while; we all know that

after

the witch’s brief reign a terrible price must be paid. But the deeper theological point is that even

while

the human witch has his or her fun, a kind of satanic victory is being enacted in the microcosmic betrayals of these fallen parishioners.

In the very beginning of the

Malleus

Institoris reveals how sophisticated and complex witch theorizing had become in the Middle Ages. There was,

for example, a prevalent psychological view of witchery, which the

Malleus

sought to discredit. Extrapolating from the early theories that we encountered in the story of Anthony, there was a school of thought that saw all evil magic and demon activity as pseudo-real. Emblematic of the medieval disputation style, Institoris considers this before he rejects it. Some people, he says, think witchcraft is illusory because “if there were harmful magic in the world, in that case something done by the Devil would exist in opposition to God’s creation. Therefore, just as it is illicit to maintain that a superstitious creation of the Devil surpasses something made by God, so it is illicit to believe that created beings and various things made by God, in [the form] of humans and beasts of burden, can be damaged by things which are done by the Devil.”

27

In other words, some theorists believed that the Creation is so inherently good (by definition of God himself), that evil must be illusory or fantastical. Moreover, if the demons actually possessed

creative

power in the world, they would be encroaching on God’s exclusive power to create. Werewolves, for example, are briefly mentioned in the

Malleus

, and Institoris walks a fine line between a purely psychological theory of man-wolf transmutation and a realist theory. The realist theory contends that the devil or an evil demon actually changes a man into a wolf; in other words, the devil

creates

a wolf where there was none a moment ago. But properly speaking, only God can create something de novo, and only God has the power to twist one species into another (an essential transformation), so this position is dangerously heretical. If this realist view is too strong, however, the psychological theory is too weak. The whole point of Institoris’s

Malleus

is to establish the very real dangers of witches and witchcraft, so it will not suffice to take the “it’s all in your head” approach. A man may become deluded and think that he has become a werewolf, Institoris explains, but that delusion is not pure fantasy. The illusion itself is caused by

malefici

, workers of harmful magic. For Institoris, there are occasional physiological hallucinations in the way we would define them today, as groundless subjective fictions caused by the body. But there are many more spirit-based misperceptions. There are good and evil apparitions, sent to us from somewhere, and the trick is to be able to discriminate the sacred from the demonic.

Institoris says that wolves will sometimes “snatch adults and children out of their houses and eat them; and they will run all over the place with great cunning, and cannot be hurt or captured by any skill, or body of men.”

28

This might be the result of natural causes, as when packs of wolves experience famine or humans get between a bitch and its pups, but Institoris rejects mundane explanations and says, “I maintain they happen through an illusion [created by] evil spirits when God punishes a people on account

of its sins.”

29

The man-eating wolves may be real animals, or they may be evil spirits appearing in that shape, or they may be real animals who have been possessed by evil spirits, but they’re probably not men who have been transformed into wolves. Institoris tells a story of a man “who used to think he was being turned into a wolf, and at these times he would hide in caves. He went there on one particular occasion and although he stayed there all the while without moving, he had the impression he had become a wolf and was going round, devouring children; and although in fact it was only an evil spirit who had possessed a wolf and was doing this, [the man] mistakenly thought (while he was dreaming) that

he

was prowling around.” Eventually this poor fellow became completely deranged by the mental illness, and they found him dithering in a forest. This madness is precisely the sort of effect that evil spirits enjoy, and such confusion, Institoris adds, is what led pre-Christian pagans to erroneously believe that people could actually transform into animals.

The

Malleus

argues throughout for this middle way between witchcraft that’s too real, and therefore in violation of God’s goodness and power, and witchcraft that is not real enough, but purely imaginative. Earlier demonologists, such as Aquinas and the authors of the influential

Canon Episcopi

,

30

argued that the frightening visions and shape-shifting episodes associated with witchcraft were really just dream-like phantasms. If any mischievous manipulation is occurring to a man who thinks he’s a werewolf, or sees his hand spin around on his wrist, or experiences aerial lift-off on a broom, the cause would have to sneak in, according to these more skeptical demonologists, at the physiological juncture where his “imaginative faculty” meets his “interior senses.” The imaginative faculty is described as a “treasure house” in each person that stores or preserves visible shapes, such as the images of animals. It’s a treasure house of memories. If some evil spirit were to trigger this storage faculty just right, it would flood the perceptual senses and give the person the illusory experience of real external stimuli. A mundane version of this happens all the time, when bodily humors trigger the treasure house in sleep and we subsequently dream.

Institoris breaks with this more prosaic version of witchcraft and offers a clever way to get demons back in their threatening positions. Works of evil, he says, are not just indigestion-like fabrications of the body. They are real and they are happening in the external world; the hand is really spinning, the children are really being eaten by wolves, the witches are really taking flight. But how is it done, if only God has true creative power?

Evil spirits, according to Institoris, do not make something from nothing when they enact their transgressions; that would truly violate the cardinal notion of a monotheistic God. It may seem that demons and their witches conjure monsters and terrors from thin air, but they do not really create in such an absolute manner. Instead, the demons have an amazing understanding of the Book of Nature. They grasp the first principles, fundamental springs, and material trajectories of physical nature itself. Demons were manipulative “scientists” long before this modern sense of the term even existed. They are the ultimate alchemists.

31