On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears (24 page)

Read On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears Online

Authors: Stephen T. Asma

Obviously the nurse of General Washington (hoax or not) is only a historical curiosity, not a monster. But Barnum’s genius was in his recognition that people would stand in line and pay for all manner of curiosities— historical, zoological, or teratological. Throughout his long career Barnum did not bother to separate the historical from the “scientific” or the purely entertaining. Curiosities were curious, no matter what their domain. Sometimes the curiosity was totally bogus, as in the case of Joice Heth, but sometimes the curiosity was a manifestly interesting body or face or creature repackaged and publicized with a bogus narrative. In this blending of natural, historical, and artificial marvels, the spirit of his collecting tendencies ran along the much earlier tracks of European

wunderkammern

.

Monsters, grotesques, and nondescripts simply formed one branch of Barnum’s tree of wondrous offerings.

After the success of Joice Heth, Barnum created a small touring circus called Barnum’s Grand Scientific and Musical Theatre. In 1841 he became the proprietor of the American Museum in New York, and a year later he hit the jackpot with the “Feejee Mermaid” and “Tom Thumb.” The Feejee Mermaid was a taxidermy hoax that must have been somewhat convincing in its day.

20

Its hybrid body, the top half of a monkey fused to the bottom half of a large fish, fooled a reporter at the

Philadelphia Public Ledger

, among many others. After an effusive paean about the gloriousness of living in the “era of progress,” the reporter gleefully proclaimed, “The greatest discovery yet made is still to be announced, and it is left for us to make the fact public.”

We have seen a mermaid!!

Start not and curl your lips in scorn, though concerning a fish it is not a

fish story

. We have seen the tangible evidence exhibited to our senses. Of the existence of that monster hitherto deemed fabulous by all the learned, though religiously believed by every salt water naturalist that ever crossed the Gulf Stream….The monster is one of the greatest curiosities of the day. It was caught near the Feejee Islands, and taken to Penambuco, where it was purchased by an English gentleman named Griffin, who is making a collection of rare and curious things for the British Museum, or some other cabinet of curiosities. This animal, fish, flesh or whatever it may be, is about three feet long, and the lower part of the body is a perfectly formed fish, but from the breast upwards this character is lost, and it then approaches human form—or rather that of a monkey.

21

Barnum drummed up public interest in this specimen by first tantalizing newspaper reporters with a phony story about trying to convince “Dr. Griffin” (also a Barnum fraud) to exhibit his astonishing specimen. Barnum invented a “curating drama” and then complained about it loudly, after which he printed posters and fliers, including illustrations of half-nude women, and eventually, when frenzy was high, announced that Griffin had acquiesced.

22

The public, and the media, swarmed.

In the weeks that followed, newspapers vacillated between astonished credulity and skeptical disgust.

23

But Barnum had succeeded in making significant profits, and he planned to make more. In a letter to his friend and Mermaid co-conspirator Moses Kimball, Barnum reveals his new taste for profitable monsters: “I

must

have the fat boy or the other monster [or] something new in the course of this week….don’t fail!”

24

In addition to bogus taxidermy, Barnum offered a steady stream of real extraordinary bodies to the paying public; some of the most well-known

were Tom Thumb (Charles Stratton, a midget), the Siamese Twins (Chang and Eng Bunker, conjoined twins from Thailand), and Jo-Jo the Dog-faced Boy (Fedor Jeftichew, a Russian with hypertrichosis, or werewolf syndrome). Current-day sentiments may find it difficult to see Barnum’s relationship with his “curiosities” as anything but exploitive, but in fact the relationship between the exhibitor and the exhibits was more complex. Tom Thumb was trained and displayed by Barnum from the time he was four years old, but he eventually became a contracted

partner

with Barnum and a wealthy man as a result, even lending money to Barnum when certain speculations failed. Some curiosities were presented with little dignity (Jo-Jo the Dog-faced Boy was expected to bark like a dog); the Siamese Twins, the Bearded Lady, and William Tillman the Colored Civil War Hero, among others, were respectfully framed and compensated.

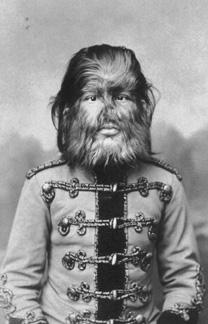

Chas Eisenmann’s photograph of Fedor Jeftichew, the Russian Dog-faced Boy (ca. 1884). From Michael Mitchell,

Monsters: Human Freaks in America’s Gilded Age: The Photographs of Chas Eisenmann

(ECW Press, 2002).

Barnum himself was a character of contradictions—in other words, quite human. His letters reveal a mixture of kind-hearted benevolence,

awe, and disdain toward his grotesques. As a showman, he appealed to the most sensationalist side of popular audiences, but he also became a teetotaler and implored his audiences in leaflets, posters, and lectures to abstain from drink and to live piously.

One of Barnum’s favorite strategies for luring the gazing public was to make the most of the liminal creature, the unnatural intermediate between natural kinds. A particularly significant liminal monster was Barnum’s famous “What Is It?” exhibit. This “non-descript,” as Barnum promoted him, was a diminutive man with abnormal physical features (real name, Harvey Leach). Barnum describes his new project in a letter to Moses Kimball: “The

animal

that I spoke to you…about comes out at Egyptian Hall, London next Monday, and I half fear that it will not only be exposed, but that

I

shall be found out in the matter. However, I go it, live or die. The thing is not to be called

anything

by the exhibitor. We know not and therefore do not assert whether it is human or animal.”

25

But the exhibit failed to draw the British public, and Barnum shelved the idea for over a decade.

The supposed appeal of “What Is It?” was the seemingly timeless interest we have in finding some creature that bridges the human-animal divide, something that mixes the ultimate taxonomic domains. Although Harvey Leach, the first “What Is It?” failed in 1846, Barnum’s second “What Is It?” an African American man named William Henry Johnson, worked like a charm after 1860. The idea behind the exhibit had come into better fashion after Darwin’s 1859

Origin of Species

put such matters before the public again. Barnum played up the “missing link” question with his new “What Is It?” suggesting in his ads that the creature was a “man-monkey.” His flier describes Johnson as “a most singular animal, which, though it has many of the features and characteristics of both the human and the brute, is not, apparently, either, but, in appearance, a mixture of both—the connecting link between humanity and the brute creation.”

26

One wonders if the racist dimension of the exhibit, offering a black man as an uncivilized transitional animal, must have played better to an American audience struggling with abolition and race questions than to the earlier audience in England, where slavery had been abolished a century earlier.

27

William Henry Johnson (1842?–1926), also known as “Zip the Pin-head,” was an African American from New Jersey whose head remained small and severely tapered while the rest of his body developed normally. Some have argued that he was a genuine microcephalic, someone with a neurological disorder resulting in reduced head size, but Johnson’s normal intelligence throws doubt on that diagnosis. The normal size of his jaw and nose were accentuated and exaggerated by the steep slope of his forehead,

and this allowed Barnum to make the “biological” suggestion of “missing link” status. Barnum dressed him in a furry suit, told audiences that he had been captured in Africa, and choreographed a show that portrayed Johnson’s increasing “civilization.”

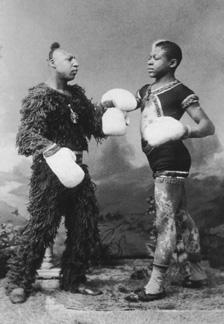

Chas Eisenmann’s photograph of William Henry Johnson, otherwise known as Zip the Pinhead (ca. 1885). Zip is pictured on the left, sparring with a “negro turning white.” He worked for both Barnum and Ringling. From Michael Mitchell,

Monsters: Human Freaks in America’s Gilded Age: The Photographs of Chas Eisenmann

(ECW Press, 2002).

Johnson drew a good salary from Barnum and eventually outlasted the Prince of Humbug, moving on to exhibit himself with the Ringling Brothers Circus. Altogether he worked as a freak for over sixty years. A year before his death, when the famous Scopes monkey trial was raging, the enterprising Johnson even offered to make himself available to the courts as “evidence” of missing links.

Many of us have seen drawings and daguerreotype images of Barnum’s famous attractions, but we also have a unique “moving image” access to one of Barnum’s late prodigies, “Prince Randian.” Prince Randian was born in the 1870s in Guyana with no limbs, just a head and a short torso. Barnum brought him to the United States and displayed him as the “human

caterpillar.” He was eventually featured in Tod Browning’s highly controversial film

Freaks

(released in 1932 and banned in the United Kingdom for more than thirty years), where his onscreen presence is both profoundly surreal as he wriggles his body through a mud puddle, carrying a knife in his mouth, and also strangely mundane as he rolls and lights a cigarette using only his mouth. In real life Randian was an intelligent man who spoke several languages, lived with his wife in New Jersey, and fathered five children. He died shortly after Browning’s film was made.

28

The film’s narrator cryptically underscores the “scientific” view of monsters, as opposed to the spiritual or moral view, when he says, “But for the accident of birth, you might be even as they are.”

The three audience responses I analyzed when discussing Shakespeare’s monsters seem relevant here, too. One could see a sideshow monster and respond with credulity, skepticism, or some intermediary reaction. In Bar-num-style hucksterism, we have completely fabricated monsters, such as the Feejee Mermaid, but also real disabled or abnormal individuals who were cloaked in fabricated exotic narratives. Often those fabricated narratives had implicit (and explicit) moral and political significance, as when white gawkers were inclined to read some monsters as evidence of a racial chain of being, an old hierarchy to which social Darwinism had given new, though spurious, credence. Monsters were intrinsically exciting but also extrinsically useful in giving audiences a sense of relief and possibly even gratitude about their own station in life.

Beyond these social implications, the purely fantastic monsters were also remarkably popular. Even when the press had definitively unmasked the hoax of some pasted-together specimen, people would line up for a firsthand experience of the spectacle. Like Shakespeare’s Blemmyae, these “natural history” monsters captured the

hearts

of audiences, even while their

minds

barred entry to the creatures. Barnum regularly claimed that the American people “loved to be humbugged,” but this was not an insult so much as a declaration of solidarity. The emotions of wonder and amazement are highly pleasurable, even when our own senses (and our mass media) turn out to be lying to us.

The Medicalization of Monsters

A woman gave birth to a child having two heads, two arms, and four legs, which I opened; and I found inside only one heart (which monster is in my house and I keep it as an example of a monstrous thing

).

AMBROISE PARÉ

W

E HAVE SEEN THAT THE ANCIENTS

interpreted monsters as omens or signs. Whether it was the birth of a hermaphrodite child or a one-horned ram, many believed the event to be a message about future military campaigns, the political wind, or the general social welfare. Monsters continued to function as portents throughout the medieval era and well into the modern. In 1642, for example, a London pamphlet reported on a frightening creature that got tangled up in a fishing net, which set the whole region on edge with worry. The pamphlet heralds, “A relation of a terrible monster taken by a fisherman near Wollage, July 15th 1642, and is now seen in King’s Street Westminster. The shape whereof is like a toad, and may be called a toad-fish. But that which makes it a monster, is, that it hath hands with fingers like a man, and is chested like a man—being near five foot long and three foot over, the thickness of an ordinary man.”

1