On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears (40 page)

Read On Monsters: An Unnatural History of Our Worst Fears Online

Authors: Stephen T. Asma

Malignant heart

is a term that appears in many state laws defining the charge of murder. The term is often used to help demarcate murder proper

from manslaughter. The State of California, for example, retains the language of “malice aforethought,” but under section 188 of the California Penal Code malice is divided into two forms: express and implied.

Express

malice exists “when there is manifested a deliberate intention unlawfully to take away the life of a fellow creature.” Malice may be

implied

by a judge or jury “when no considerable provocation appears, or when the circumstances attending the killing show an abandoned and malignant heart.”

Perhaps a criminal monster is one who

chronically

acts from a malignant heart. In that case the difference between a monstrous action and a monstrous person can be detected by the mark of recidivism or recurrence. The law recognizes, albeit with a very high burden, the insanity defense, and even recognizes voluntary intoxication as grounds for denying a malignant heart. A malignant heart suggests that a person’s crimes were not so much

situational

as character-based.

56

One criminal act by itself, even a brutal one, is very difficult to read. If that act is a single page in a whole book of weird and crazy behaviors (attested to by credible witnesses), it would indicate something quite different from a case of built-up rage (e.g., the Columbine massacre), and that kind of brutal act would look different still against the backdrop of a repeatedly mean and abusive pattern of behaviors.

IN THIS CHAPTER I HAVE

articulated the major contours of a twentieth-century view of criminal monsters. Instead of fading away in the light of clinical, pharmaceutical, and psychological theory improvements, the concept of monster has kept going strong, doing significant work for us. Although the term

monster

is overused and often obfuscates important complexities, the more professional semantic contenders, such as

psychopath

, are not exactly great leaps forward. Even the law is still using wonderful terms like

malignant heart

. We are still very much at the

descriptive

phase of the science of the criminal mind, not yet at the underlying

causation

phase. Some people like to point to the astounding complexity of the brain and the nature-nurture dialectic to undermine the quest for scientific certainty. But perhaps it’s not the complexity of a criminal mind that makes many of us despair of scientific comprehension. Perhaps instead, when we think about the horrific crimes of our day, we lose the desire to comprehend.

5

Monsters Today and Tomorrow

Torturers, Terrorists, and Zombies

The Products of Monstrous Societies

XENOPHOBIA AND RACESituational forces can work to transform even some of the best of us into Mr. Hyde monsters, without the benefit of Dr. Jekyll’s chemical elixir

.

PHILIP ZIMBARDO

A

FTER THE MODERN-DAY

M

EDEA

, Susan Smith, drowned her children in 1994, she went to authorities claiming that an African American man had stolen her car and driven off with her children. America was all too willing to accept this bogus story, and tearful entreaties and national manhunts ensued for almost two weeks, until Smith confessed to driving her kids into a lake. The carjacking, kidnapping black monster tapped into a barely submerged fear in mainstream America.

In 1899 Stephen Crane wrote a short story titled “The Monster.” In this sad novella, a small-town doctor named Trescott almost loses his son in a house fire, but a black man named Henry Johnson bravely saves the boy’s life. In the rescue, Johnson is horribly burned and deformed by the fire, but he lives and eventually rejoins society. Society, however, is not ready to receive him. His casual appearance at a neighbor’s home causes genuine terror and flight; his attempt to sit quietly in the town square brings the jeers and taunts of children. At one point he is thrown in jail and a mob forms simply because the town is so frightened of his appearance. Dr. Trescott, who gratefully took Johnson under his care and protection, begins to feel the sting of social rejection himself. The novella ends without resolution

but with the suggestion that Trescott and his family will share Johnson’s pariah status interminably. Henry Johnson may be interpreted as a symbol of the monstrous black male, a creature composed largely of projected fears and anxieties. Dr. Trescott represents the attempt to see beyond such demonization to the humanity of the black man, and he is punished for his goodwill by the mob, which clings to its convenient enemy.

The story is even more poignant when we consider it in light of the 1892 lynching of Robert Lewis in Port Jervis, New York. Stephen Crane’s brother William was a judge living in Port Jervis; on June 2 he heard a mob forming in the street outside his house. Robert Lewis had been accused of raping a white woman named Lena McMahon, and his police wagon was attacked by a vengeful mob on its way to the jail. Lewis was dragged to East Main Street and a rope was thrown around William Crane’s front tree. When Crane rushed out of his house “the body was going up” and he saw that “the negro’s hands were tied and his elbows were crooked.” Crane shouted, “Let go of that rope!” and the crowd quieted slightly, letting Lewis’s body descend somewhat. “Again I shouted,” Crane explained at the inquest, “and gave a jerk on the rope and it came loose in my hands and the negro fell into the gutter on his back. I pulled the rope down from the tree and loosened the noose from his neck and took it off.”

1

Crane then enlisted the help of a nearby policeman to “protect that man.” But the mob began to grow bold again and move in on Lewis and his few protectors. “I could see that he was alive,” Crane reported later. “He was gasping for breath and his whole body was quivering. His face was covered with blood and I did not recognize him.” A doctor emerged, and after a lightning-quick examination suggested to Crane that Lewis would survive if they could get him to a hospital. At this point a member of the mob, Robert Carr, stepped forward and shouted, “He ought to be hung.” Crane recounted that “the crowd then took up the cry, ‘hang him!’ ‘don’t let the doctor touch him!’ hang all the niggers!’ ” At this point a fight broke out, a struggle to get possession of the rope. Crane resisted, but the crowd was too strong and the noose ended up around Lewis’s neck again. Crane said, “The next I saw of it, it was over the branch of the tree again. I sprang to the tree and caught hold of the rope and tried to pull it down but there were too many at the other end.” Crane was overpowered and Robert Lewis was lynched a second time.

As in many other lynchings, this vigilante justice appears to be as symbolic as it is literal. In his essay “The Dramaturgy of Death” Gary Wills argues that most public executions of criminals throughout history have been motivated by obscure emotional impulses rather than rational theories such as deterrence. The community sees the killing as a kind of cleansing. Lynch mobs, for example, project impure traits onto a surrogate monster

or further vilify real criminality so that it stands for all things impure and then seek to destroy and cleanse the impurity. Wills explains that “forms of extrusion require society’s purification by destruction of a polluted person. Unless society or its agents effect this purification, the pollution continues to taint them.”

2

As the scholar Elaine Marshal describes the lynching of Robert Lewis, a single black man becomes a stand-in for the impurities that social prejudice accuses the entire black male population of embodying: “For the crowd Lewis is more than ‘a negro’ in this scene; he becomes ‘the negro,’ the faceless representative of the whole ‘race.’ That is the clear import of the transition in the mob’s cry from ‘hang

him

’ to ‘hang

all

the niggers.’”

3

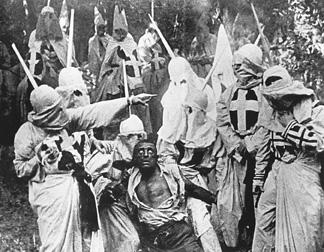

Demonization and race. The Ku Klux Klan lynches the black character “Gus” (played by actor Walter Long in blackface) in D. W. Griffith’s inflammatory film

The Birth of a Nation

(1915). Image courtesy of Photofest.

The myth of the black monster has had a prosperous career in the twentieth century, first in the Jim Crow era of public lynchings, then in the reactions to the civil rights struggle, and now in the well-known statistics that one in every twenty black men over the age of eighteen is incarcerated in the U.S. prison system.

4

But the myth itself is very old. Recall that the medievals tended to blend the extreme monstrous races (e.g., Blemmyae, Sciopodes) with the foreign ethnicities of Africa, India, and the Middle

East. Debra Higgs Strickland points out that “Ethiopians were often idealized as a pious and ‘blameless’ people in the writings of the ancient Greeks, such as Homer. But in European Christian eyes, Ethiopians were monstrous principally owing to their black skin, which was considered a demonic feature.”

5

One of the main reasons black-skinned people were more maligned in medieval Europe than in Mediterranean antiquity is that there were fewer of them around to serve as counterevidence to the unchecked gossip and fear-mongering; very few Africans lived in Europe before the twelfth century. But as I traced earlier in my discussion of the Christian Table of Nations, there were theological prejudices at work as well. “Black was a color,” explains Strickland, “associated with evil, sin, and the devil, especially in patristic writings. For example…St. Jerome stated that Ethiopians will lose their blackness once they are admitted to the New Jerusalem, meaning that their external appearance will change once they become morally perfect.”

By this point we have already seen many of the negative associations that a hostile imagination can produce for any perceived other (e.g., unclean, barbaric, sexually illicit, spiritually deformed). Demonizing or monstering other groups has even become part of the cycle of American politics. The social construction of an enemy is built into the generational dynamic of a melting-pot democracy. According to the sociologist James A. Aho, any sample of American history will reveal a redundant dynamic between three generations: those currently in power, a second generation that’s waiting to take the reins, and the children of the first group. The first group rules for approximately fifteen years, “focusing on the foreign or domestic enemy that provides it, by negation, with that generation’s identity as ‘good Americans’: niggers, fags, papists, spics, commies, nips, Nazis, huns, Satanists, or dope-crazed sex fiends, all drawn from the storehouse of American demonology.”

6

But because these “enemies” are largely collective projections and not real causes of social ills, the policies aimed at fixing them fail. The next generation, disgusted by the empty posturing of the first, eventually comes into power and replaces the elders with “visionaries” who can penetrate down to the true causes of social problems, and those true causes tend to be identified as the policies of the predecessors. But the third generation, the children of the first, get their turn at power thirty years after their parents. That third generation, Aho claims, now begins “reciting publicly the myths of evildoers first heard at the feet of their now-deposed fathers.” And the cycle starts over.

Obviously race has played a large role in this sociopolitical dynamic. Seeing other races and ethnicities as monstrous has not just helped cynical domestic politics, but has also aided much of the international warfare

of the twentieth century. The Jews were reconstructed as monstrous vermin by the Nazis, the Vietnamese were reconstructed as soulless gooks, and according to one U.S. soldier, Mike Prysner, the Iraqis and Afghanis are regularly referred to by military personnel as “camel jockeys,” “towel heads,” and “sand niggers.”

7

A Vietnam veteran in the documentary

Faces of the Enemy

says, “You’re trained as a soldier to see your enemy as an abstraction. You have to. The soldier’s most powerful weapon is not his weapon, but his idea of the enemy.”

8