Overlord (Pan Military Classics) (54 page)

Read Overlord (Pan Military Classics) Online

Authors: Max Hastings

‘Goering! The Luftwaffe’s doing nothing.’ [Guderian reported a confrontation that August] ‘It is no longer worthy to be an independent service. And that’s your fault. You’re lazy.’ When the portly Reichsmarschall heard these words, great tears trickled down his cheeks.

24

Hitler placed the principal responsibility for failure at Mortain upon von Kluge’s lack of will. Yet he seemed far more depressed by small personal tragedies, such as the death of his former SS orderly, Captain Hans Junge, who was killed by Allied strafing in France. He broke the news personally to the man’s widow, his youngest secretary, Traudl Junge: ‘

Ach

, child, I am so sorry; your husband had a fine character.’

25

When von Choltitz reported to Hitler fresh from the front, he was informed that the Führer was about to hurl the Allies into the sea. The general concluded that ‘the man was mad’.

26

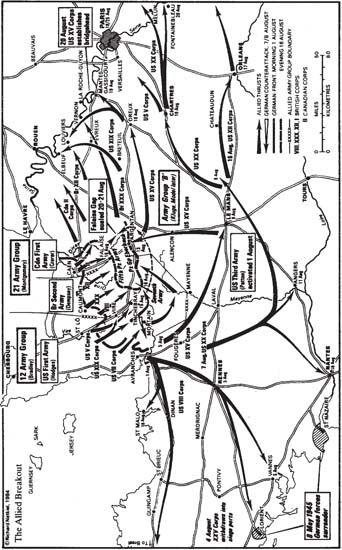

On 11 August, with Haislip’s XV Corps still pushing east around Alençon, it became Montgomery’s responsibility to consider setting a new boundary between the American, British and Canadian forces, which expected to meet east of the German armies imminently. Despite the changed circumstances, he declined to alter the line he had set near Argentan on 6 August. He believed that XV Corps would meet slow going on its turn north, where it re-entered the

bocage

, which the Germans could exploit to their advantage. It seemed reasonable to assume that the Canadians, pushing south across reasonably open country, would be in Argentan before Haislip. The new boundary, the point at which XV Corps

would halt its advance, was therefore set just south of Argentan. Patton nonetheless warned Haislip to be ready to push up to Falaise, despite the corps commander’s fears that his division would not prove strong enough to hold a trap closed in the face of the wholesale retreat of Army Group B. Patton urgently began to seek reinforcement from XX Corps and from Brittany. Just before midnight on the 12th, Haislip informed Third Army that his 5th Armored Division was just short of Argentan. Did Patton wish him to continue north to meet the Canadians? Patton now telephoned Bradley with his legendary demand: ‘We have elements in Argentan. Shall we continue and drive the British into the sea for another Dunkirk?’

27

Despite Bradley’s refusal, Patton anyway ordered Haislip to advance cautiously north of Argentan. Only at 2.15 p.m. on the 13th did XV Corps receive categoric orders to halt at Argentan and recall any units north of the town. Bradley’s staff had consulted 21st Army Group about a possible boundary change, but were refused it. Patton wrangled with Bradley until at last, having taken care to ensure that the circumstances of the order to halt were made a matter of record, he acquiesced. Bradley was always at pains to make it clear that he himself opposed any further push north, irrespective of the opinions of Montgomery. He feared, as Haislip did, the danger of presenting a thin American front to German troops who would have no alternative but to seek to break through it. Throughout the days that followed, he resolutely refused to press Montgomery for a change in the boundaries.

On the ground, the situation was developing imperatives of its own as resistance stiffened in front of Haislip. 116th Panzer – with 15 surviving tanks – and elements of 1st SS and 2nd Panzer – with 55 tanks between them – were now deployed on his front. The Germans had still made no decision to attempt to flee the threat of encirclement. As mopping up around Mortain was concluded and forces of the US First Army became available to move east, Collins’s VII Corps began a rapid advance north-east from Mayenne on the 13th. At 10.00 a.m. that day, Collins telephoned First Army

in a characteristically ebullient mood, asking for ‘more territory to take’. First Army’s diary recorded:

1st Div was, in some places, on the very boundary itself, and General Collins felt sure that he could take Falaise and Argentan, close the gap, and ‘do the job’ before the British even started to move. General Hodges immediately called General Bradley, to ask officially for a change in boundaries, but the sad news came back that First Army was to go no further than at first designated, except that a small salient around Ranes would become ours.

Bradley, curiously enough, claimed now to be convinced that the importance of closing the trap at Falaise had diminished, because most of the Germans had already escaped eastwards, a view which neither Ultra nor air reconnaissance confirmed. For whatever reasons, he switched the focus of American strategic energy east, towards the Seine. Haislip, he told Patton, was to take two of his four divisions east, while the remainder, with VII Corps, remained at Argentan. It was almost as if Bradley had lost all interest in the ‘short envelopment’ which he himself had proposed to Montgomery on 8 August. He now seemed determined instead to concentrate upon trapping the Germans against the Seine, the rejected ‘long envelopment’. In these days, an uncharacteristic uncertainty of purpose, a lack of the instinct to deliver the killing stroke against von Kluge’s armies, seemed to overtake Bradley. General Gerow of V Corps, sent to take charge of the situation at Argentan after Haislip’s departure, found the command there almost completely ignorant of the whereabouts of the Germans, or even of his own men.

But now Montgomery and Bradley at last agreed that they would enlarge the scope of the pocket eastwards, and seek to bring about a junction of the Allied armies at Chambois. Their plans had thus evolved into a series of compromises: instead of the ‘short envelopment’ through Argentan–Falaise, Haislip was launched upon the ‘long envelopment’ to the river Seine, while Gerow and

the Canadians in the north attempted to complete the trap along a line between them. On the night of 17 August, 90th Division attacked north-east to gain the Le Bourge–St Leonard ridge commanding the approach to Chambois. On their left, the raw 80th Division attempted to move into the centre of Argentan. The commanding officer of their 318th Infantry described his difficulties:

This was our first real fight and I had difficulty in getting the men to move forward. I had to literally kick the men from the ground in order to get the attack started, and to encourage the men I walked across the rd without any cover and showed them a way across. I received no fire from the enemy and it was big boost to the men. A tank, 400 yards to our front, started firing on us and I called up some bazookas to stalk him. However the men opened fire at the tank from too great a range and the tank merely moved to another position. I walked up and down the road about three times, finding crossings for my troops. We advanced about 100 yds across the rd and then the Germans opened up with what seemed like all the bullets and arty in the world. I call up my tanks . . . When my tanks came up we lost the first four with only eight shots from the Germans.

28

The Germans held the 90th Division through the night of 18/19 August south of Chambois, and it was only in the morning that the first American elements reached the village. All the next day and night, the 90th’s artillery pounded Germans fleeing east from encirclement. The 80th Division secured Argentan only on the 20th. Bradley’s divisions had effectively stood behind the town for over a week.

Hundreds of thousands of Allied soldiers at this time hardly understood the enormity of the events unfolding around them. They knew that some days they had moved a little further, some days a little less; that some days they encountered fierce German resistance, and on others it seemed, incredibly, as if the enemy’s

will was fading. In a field near Aunay-sur-Odon in the British sector on 14 August, a tank wireless-operator named Austin Baker was camped with his squadron of the 4th/7th Royal Dragoon Guards:

We hadn’t been there more than a couple of hours when everybody in the regiment had to blanco up and go over by lorry to the 13/18th Hussars area to hear a lecture by General Horrocks, who had just taken over command of XXX Corps. He was very good, and made us feel quite cheerful. He told us about the Falaise pocket – how the German Seventh Army was practically encircled and how the RAF were beating up the fleeing columns on the roads. He said that very soon we should be breaking out of the bridgehead and swanning off across France. That seemed absolutely incredible to us. We all thought that we should have to fight for every field all the way to Germany. But Horrocks was right.

29

Through most of the campaign in north-west Europe, while there were tensions between the American and British high commands and each army possessed a large stock of quizzical jokes about the other, there was no real ill-will between the soldiers. ‘We knew that they were the chaps that mattered,’ said Major John Warner of British 3rd Reconnaissance Regiment about the Americans. ‘We couldn’t possibly win the war without them.’

1

But during the weeks between the start of COBRA and the march to the Seine, many men of the British Second Army and the newly-operational Canadian First Army found the blaring headlines about the American breakout, their armoured parade through Brittany and down to the Loire, a bitter pill to swallow. Much more than most armies in most campaigns, they were very conscious of the press. They received newspapers from England only a day or two after publication, and studied avidly the accounts of their own doings in Normandy. They saw photographs of jubilant American infantry, helmets pushed back and weapons slung, waving as they rode their tanks through liberated villages alive with smiling civilians. They studied the sketch maps that revealed their allies controlling tracts of country far greater than their own overcrowded perimeter. Above all, they read of the light opposition that the advance was meeting. An NCO of 6th KOSB asked his commanding officer bitterly, ‘if it was the high command’s intention to wipe out all the British and finish the war with the Americans.’

2

For throughout the weeks of COBRA, Brittany, Mortain, almost every day the British and Canadians were pushing slowly forward on their own front with much pain and at heavy cost. The British

VIII and XXX Corps were attacking on an axis south-east from Caumont, while the Canadians moved directly south from Caen towards Falaise. Second Army was still in thick country, facing an unbroken German line with far greater armoured strength and

Nebelwerfer

support than anything the American Third Army encountered. Only immediately before the Mortain counter-attack did the weight of German armour begin to shift dramatically eastwards. Most of Dempsey’s men were very tired by now, above all the infantrymen of 15th Scottish, 43rd Wessex and 50th Northumbrian divisions, who had borne so much of the heaviest fighting, and continued to do so. It was a matter of astonishment to officers of other units that 43rd Division still retained any morale at all. Its commander, Major-General G. I. Thomas, was a ruthless, driving soldier for whose determination Montgomery was grateful, but who had earned the nickname ‘Butcher’ for his supposed insensitivity to losses. The purge in XXX Corps when Montgomery sacked Bucknall, together with Erskine and Hinde of 7th Armoured, dismayed many of the 7th’s men, but did not produce a dramatic improvement in performance.