Pandora's Keepers (27 page)

Authors: Brian Van DeMark

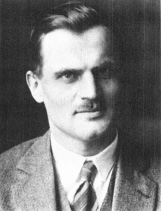

Ernest Lawrence (1901–1958), American experimental physicist who invented the first high-energy particle accelerator, the

cyclotron, and founded the Berkeley and Livermore National Laboratories. An early advocate of government support for atomic

research in 1941, he opposed development of the superbomb immediately after the war but later changed his mind. (

Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives

)

Arthur Compton (1892–1962), American physicist who chaired the governmental advisory committee in 1941 that assessed fission’s

military potential. He later directed the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago, where scientists researched

plutonium and the nuclear chain reaction. He abandoned weapons work after the war. (

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, W. F Meggers Gallery of Nobel Laureates

)

Robert Oppenheimer (1904–1967), American theoretical physicist who led development of the atomic bomb as director of the Los

Alamos National Laboratory from 1943–1945. After the war, he sought to resolve the political and moral problems arising from

nuclear weapons but fell victim to an anticommunist witch-hunt. (

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives

)

Hans Bethe (1906–2005), German-born American physicist who led the Theoretical Division at Los Alamos during the war and reluctantly

participated in development of the superbomb after the war. He later became a leading critic of the nuclear arms race and

the policy of nuclear superiority championed by Edward Teller. (©

CORBIS

)

THE NETWORK

Niels Bohr (second from left) stood at the center of a close-knit network of European and American physicists in the 1920s

and 1930s. Here he meets with younger colleagues, including Edward Teller (second from right) and Otto Frisch (far right).

(

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Wheeler Collection

)

Robert Oppenheimer (wearing hat) and I. I. Rabi (holding sheet), two American postgraduates in Zurich, summer 1930, with Wolfgang

Pauli (far right). In Europe, Oppenheimer and Rabi learned the latest physics, witnessed the rise of Nazism, and watched war

clouds gather over the Continent. (

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives

)

Robert Oppenheimer and Ernest Lawrence summering at Oppenheimer’s New Mexico ranch, 1931. They were very different, but they

complemented each other professionally and liked each other personally—until political differences after the war sundered

their friendship. (

Molly B. Lawrence, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives

)

Robert Oppenheimer, Enrico Fermi, and Ernest Lawrence at the Rad Lab, Berkeley, in the summer of 1937. Fermi was visiting

America from Italy, which he would leave the following year to escape Fascist persecution of his Jewish wife and children.

(

Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, courtesy AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives

, Physics Today

Collection

)

Participants at the Washington Conference on Theoretical Physics, January 1937. The annual conference attracted talented physicists

from both sides of the Atlantic. Those attending in 1937 included Hans Bethe (front row, fourth from left), I. I. Rabi (above

Bethe’s left shoulder), Niels Bohr (front row, second from right, wearing scarf), and Edward Teller (partially obscured, standing

directly behind Bethe, two rows up). (

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Gamow and

Physics Today

Collections

)

THE MANHATTAN PROJECT

Leslie Groves (1896–1970), U.S. army general who directed the Manhattan Project during the war. He oversaw all aspects of

the project: scientific, production, security, and planning for use of the bomb. Under his direction, project plants were

built at Oak Ridge, Tennessee; Hanford, Washington; and Los Alamos, New Mexico. (©

CORBIS

)

A weekend hiking excursion in the Jemez Mountains near Los Alamos, winter 1944–1945. Such outings offered one of the few opportunities

for scientists such as Enrico Fermi and Hans Bethe (first and second on left) to relieve the stress of working on the bomb.

(

AIP Emilio Segrè Visual Archives, Segrè Collection

)