Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light (27 page)

Read Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light Online

Authors: David Downie

Tags: #Travel, #Europe, #France, #Essays & Travelogues

As we walked from room to room in the château the tableaux and voices changed automatically with eerie ease, activated by motion sensors. Here were Haussmann’s comfortable new buildings aligned on wide boulevards, with new train stations, grand cafés, legally registered whorehouses, iron bridges, bourgeois families out for a stroll. Here, too, were dozens of wonderful political cartoons hanging on the walls or projected on a screen. All referred to the works of the Impressionists. In one a disgruntled viewer comments:

These paintings need to be seen from afar!

Another retorts:

I know, that’s why I’m leaving

. Other rooms faithfully reproduced historic Paris interiors where nineteenth-century music-hall songs played, the period’s charm and seediness evoked side by side.

By the time we’d learned in a replica Impressionist Café-Théâtre about the irresistibility of absinthe (the LSD of the nineteenth century); waited in a mock-1870s Paris train station; then “ridden” the steam train out through beautiful projected countryside to Auvers, the way the Impressionists did, we were both thoroughly taken in. Having already eaten our giant omelets earlier, we resisted the temptation to lunch at the château’s Impressionist

guinguette

—a popular eatery as depicted in the paintings of Renoir et al.

This may be Auvers’s answer to Disneyland Paris, I thought, but it’s cleverly and intelligently done, the best evocation of the City of Light in its heyday I have yet to encounter. Even the silly, computer-modified image of Monet’s self-portrait blinking its eyes at you is contagiously funny.

There was just enough time to get to the Auberge Ravoux before it closed. We raced a mile or so back through town and squeezed in. The auberge dates back to 1855. It faces the town hall on one side, a cobbled courtyard on the other. In Vincent’s day its owners sold wine and wood, served meals, and rented out three rooms upstairs. Authur Gustave Ravoux took it over not long before Van Gogh arrived. For 3.50 francs a day the Dutchman got a tiny room and three squares: meat and vegetables, salad, and bread.

Theo Van Gogh had probably hoped that his ailing brother could stay at Dr. Gachet’s house and get treatment there, but that proved impossible. So he arranged for another young Dutch painter named Anton Hirschig to move into the room next door to Vincent’s at the auberge and keep an eye on him. No one really knows precisely where or with what kind of gun Vincent shot himself. He managed to get back to the auberge, drag himself upstairs, and hang onto life for a painful day and a half. After he died, no one wanted to sleep in the room of an insane suicide victim, so it was used for storage and somehow escaped alteration.

Having paid the entrance fee we climbed up to the room via a well-stocked, luxurious bookstore-boutique on the second floor. The Auberge Ravoux is no longer a quaint little inn: shortly after Van Gogh’s paintings became the most valuable in the world, in 1987, a businessman named Dominique-Charles Janssens bought the place, created the Institut Van Gogh, restored the building to its original configuration, and in the early 1990s reopened it as the Maison Van Gogh, a tourist attraction. Janssens did a consummate job.

From the bookshop we opened a shabby old door and hiked up the final flight of steps. Anton Hirschig’s room had been restored to its 1890s simplicity: period wallpaper, a single box-spring bed, a washbasin and chest of drawers. Vincent’s even smaller room next door was barren, without furniture or wallpaper. You could taste the raw plaster in the air. On one side of the room was an empty plate-glass display case with an extract from a June 10, 1890, letter Vincent wrote his brother Theo: “Some day or other, I believe I will find a way to have my own exhibition in a café.”

Starting in the mid-1990s Janssens’s institute began lobbying France’s museum bureaucracy for permission to decorate the room with

Landscape of Auvers After the Rain

(at the Pushkin Museum, in Moscow), but decades have now gone by. The empty bulletproof display case conceived for it clashed somewhat with the garret’s spartan walls and somber mood, which generated the same shrine-like quality as the Maison du Dr. Gachet. Janssens’s desire to exhibit a real Van Gogh seemed perfectly understandable. The restored auberge draws about seventy thousand paying pilgrims a year. With a multi-million-dollar original in Vincent’s room that number would soar.

In the third upstairs room we watched a twelve-minute video about Vincent’s seventy days in Auvers. Skillfully made, with music by Richard Strauss, it pressed all the right buttons. I blew my nose and dried my cheeks as we walked downstairs and dropped thirty dollars for a thin book on Vincent’s life in Paris and Auvers. I resisted the temptation to buy the Van Gogh–inspired cookbook.

Our last stop was the ground-floor restaurant, an authentic recreation of something a bourgeois traveler could have experienced hereabouts a century ago, with wooden tables, period settings, and carafes and glasses designed to look like those in the Van Gogh painting

L’Absinthe

. The restaurant quickly became a favorite among Paris’s glitterati. Hanging on a wall was a sketch by the celebrated French political cartoonist Sempé. In it a throng is trying to get into the Grand Palais for a Van Gogh exhibition. The caption says, “This is the guy who wanted to have a show in a café …”

Beaumarchais’s Marais

Je me presse de rire de tout, de peur d’être obligé d’en pleurer

. (I make myself laugh at everything, for fear of having to weep.)

—P

IERRE-

A

UGUSTIN

C

ARON DE

B

EAUMARCHAIS

,

The Barber of Seville

ou can walk across the Marais in half an hour or, like me, spend a lifetime exploring the leafy squares, alleys, and mossy courtyards of one of Paris’s more atmospheric neighborhoods. They’re woven along imperfectly traced arteries between the Bastille and Beaubourg, the Seine and Temple, in the 3rd and 4th arrondissements. Nowadays

ou can walk across the Marais in half an hour or, like me, spend a lifetime exploring the leafy squares, alleys, and mossy courtyards of one of Paris’s more atmospheric neighborhoods. They’re woven along imperfectly traced arteries between the Bastille and Beaubourg, the Seine and Temple, in the 3rd and 4th arrondissements. Nowadays

le shopping

may well be what draws most visitors to this self-consciously chic theme park for what Parisians call

bobos

—bohemian bourgeois. Boutiques, art galleries, and faux-bistros are shoehorned wall-to-wall between museums and administrative offices in landmark Louis-something townhouses.

But behind the restored façades and under the cobbles lurk layers of history. Since the mid-1980s I’ve lived near Place des Vosges, the neighborhood’s centerpiece, and when it comes to understanding and appreciating the Marais I’ve barely scraped the icing off the layer-cake.

Despite its inauspicious name

—marais

is old French for swamp or marsh—and equally murky proto-historical days as a floodplain, the neighborhood has long lured an impressive roster of humanity. Some contemporary admirers like to hark back thousands of years, but in my wanderings I’ve never heard the rumble of chariots on Rue Saint-Antoine (the neighborhood’s ancient Roman backbone) or the clatter of medieval knights en route to their fortresses at the Bastille or Temple. But echoes from the Marais’s past, especially those from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries’ Golden Age, continue to resonate above the white noise of cell phones and street-corner ensembles. One voice in particular often calls out to me, the voice of Pierre-Augustin Caron, better known as Beaumarchais. “I make myself laugh at everything,” Beaumarchais’s Figaro famously quipped, “for fear of having to weep.”

Clockmaker, musician, playwright, pamphleteer, arms dealer, and spy, Beaumarchais was born in 1732 on Rue Saint-Denis, a few blocks west of the Marais, and later lived in a Rue Vieille-du-Temple mansion in what’s now the Marais’s gay district. He died in 1799, having made and lost several fortunes, in an extravagant palace he’d built on Boulevard Beaumarchais, abutting Place de la Bastille and Boulevard Richard Lenoir. Beaumarchais certainly loved the Marais. Would he love it today?

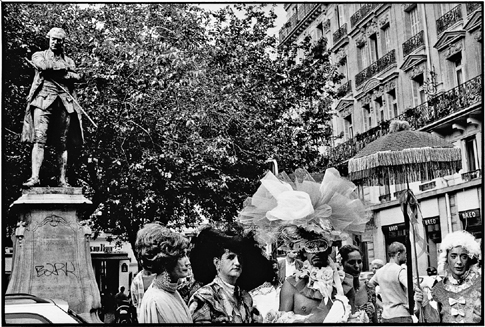

A bronze statue on Rue Saint-Antoine in a small square on the corner of Rue des Tournelles shows a handsome, vigorous Beaumarchais. His walking stick is bent: for the last hundred-odd years people have been hanging bouquets from its tip, during the protest marches that start at Place de la Bastille and, traditionally, move up Rue Saint-Antoine to city hall or along Boulevard Beaumarchais to Place de la République. A hotel just off Rue de Rivoli, and plaques on walls scattered here and there, bear Beaumarchais’s name. They remind the Marais’s window-shoppers that Beaumarchais was the author of the plays

The Barber of Seville

and

The Marriage of Figaro

.

Like the neighborhood’s façades and cobbled recesses, these physical testimonials open the doors of speculative fancy. To my mind what really makes Beaumarchais ever present amid the Marais’s bumper-to-bumper trendies is his eerily contemporary, disconcertingly ambiguous character. It merged in a single person the brutal contradictions and wild paradoxes of an age more like our own than many might think. If such a thing as “spirit of place” exists then Beaumarchais’s might very well have been—and still be—the spirit of the Marais and that of many of its residents: ambitious, litigious, subversive, licentious, arrogant, nostalgic, progressive, enlightened, opportunistic, self-important, at once aristocratic and thoroughly parvenu. Sound like the designers, architects, statesmen, fashion models, and starlets who call the Marais home today?

If he were alive the contrarian Beaumarchais would probably be director of the Opéra de la Bastille, receiving a salary plus subsidies (as a librettist, musician, and playwright) from the Ministry of Culture while simultaneously trying to dismantle the old-boy bureaucracy sustaining him. Since Boulevard Beaumarchais is traffic-clogged and undistinguished nowadays, he might choose instead to live in, say, the quietly posh Place des Vosges, perhaps in the same restored townhouse as former Socialist minister Jack Lang. Or maybe he’d gut and reconvert a historic property in Rue des Francs-Bourgeois, like celebrity architect Jean Nouvel, whose bald pate and flashy black designer-wear are a neighborhood curiosity.

More likely, Beaumarchais would knock down a landmark mansion or two and build something new, vast, and provocative—after all, he was a passionate innovator, and he did help bring down the sclerotic Ancien Régime despite his closeness to Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. Doubtless a modern Beaumarchais would dine regularly at such Michelin-starred Marais perennials as L’Ambroisie or Benôit, breaking bread with politicos from left and right, needling and wheedling both, soliciting and dispensing kickbacks, making and breaking allies and enemies alike. Perhaps he would lobby the Greens to turn the Marais into a car-free zone, as some misguided inhabitants are currently trying to do, while ensuring that he could still drive his SUV or Ferrari to his sumptuous digs (and those of his many mistresses).

“Drinking when we’re not thirsty and making love year round, Madame, that’s all that distinguishes us from other animals,” sang Figaro. And, as Beaumarchais’s biographers agree, Figaro and his creator were one and the same.

It was among the clocks, jewels, and musical instruments with which his father was entrusted that Beaumarchais, barely out of his teens, invented a spring mechanism that made watches run more accurately. And it was in defending his invention from Jean-André Lepaute, the royal watchmaker who stole his idea, that Beaumarchais demonstrated his preternatural talents as writer and orator. He won his case before the Academy of Sciences and soon replaced Lepaute at Louis XV’s Versailles court, quickly becoming, among other things, harp instructor to the king’s daughters, the associate of the kingdom’s biggest arms dealer, and protégé of the king’s official mistress, Madame de Pompadour.

The young Beaumarchais craved respectability, and while the city’s best addresses at the end of Louis XV’s reign were being built in the Left Bank’s Saint-Germain neighborhood, the Marais was still a fashionable enclave, just as it is now, for bluebloods and professionals at the top of their career. Only after years of social climbing, court intrigue, spying on the king’s behalf, gunrunning, and two marriages (the first to a rich widow with a property named “Beaumarchais,” whence his title) did the watchmaker-become-nobleman manage to move from Versailles via London to a Marais townhouse. That townhouse was the luxurious Hôtel Amelot de Bisseuil, often called the Hôtel des Ambassadeurs de Hollande, in Rue Vieille-du-Temple.