Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light (23 page)

Read Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light Online

Authors: David Downie

Tags: #Travel, #Europe, #France, #Essays & Travelogues

Zola also said that Moreau had had no master and would have no disciples. But Zola was wrong. Rouault, Matisse, Marquet, and many others were his pupils at the École Nationale des Beaux-Arts. Odilon Redon, better known nowadays than Moreau himself, was heavily influenced by the mystic’s work, as were Picasso, Dalí, and Matta.

With a well-to-do family behind him, a secure job, and regular patrons, Moreau was the antithesis of the starving artist. Only once did he deign to show his work in a commercial gallery. The real motive for his reticence was a morbid fear of criticism. In the last years of his life he worked frantically to give titles to his pictures and to write notes about them so that future critics—and museumgoers—would not misinterpret them.

Several years after my first visit, I returned to the Moreau museum (and have been back many times since). I was not alone this time. The doorbell had been disconnected and the dust removed. Somehow the mystery was gone, and with it much of the magic. As the guard had said, the best pictures were on the third floor—gemlike canvases sparkling with cobalt and gold that Moreau had labored over for months or years.

The hundreds of watercolors and drawings mounted on ingenious wooden stands revealed another Moreau. Here were gentle landscapes and fine sketches with all the mystical power of the oils, but none of the tortured anguish. Here too was the self-portrait I had first seen on that old postcard, which I had lost in the meantime. Moreau had been commissioned to draw it by the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. It was to have hung in the Vasari Corridor, among the self-portraits of history’s greatest painters. But Moreau, believing himself unworthy, had never delivered it. He wished to disappear as a man, and live on in his works, at his museum.

At the Montmartre Cemetery later that day I asked a caretaker where I could find Moreau’s tomb. No one had ever asked for it before, he sniffed, and he’d never heard of the man. I gave the full name and the year Moreau died. After digging out an enormous leather-bound ledger marked

sépultures des célèbres

, the caretaker huffed and puffed and searched laboriously. He was startled to hit upon the entry, and was clearly disappointed not to send me away with a wag of the finger. The tomb, registered in a meticulous Belle Époque hand, was in section twenty-two, row seven, gravestone number two, he said. But I was unsure that day whether I’d found it. The headstone had fallen over, and the name engraved below was worn and mossy. It seemed appropriate, a fate of which the Symbolist would have approved. Cleaned and restored since then, like his museum, Moreau’s resting place is no longer dark, forgotten, and mysterious. But the enigma of the man remains.

The Perils of Pompidou

Cernimus exemplis oppida posse mori …

(We learn from example that cities, too, can die …)

—R

UTILIUS

C

LAUDIUS

N

AMATIANUS

,

De Reditu Suo

, fifth century

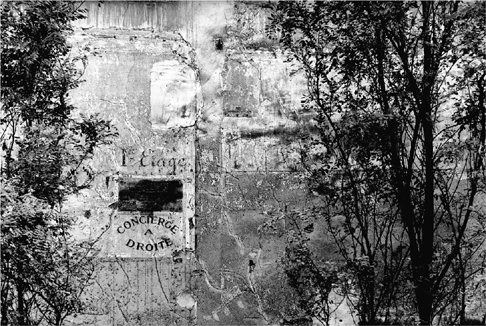

ew cities can claim a tradition of urban vandalism nobler than that of Paris. Perhaps it’s genetic: archaeologists insist the Gauls burned their Seine-side settlements before going to battle, thus depriving rivals of the pleasure. Julius Caesar and his descendants endlessly reconfigured their fledgling city, as did generation upon generation of kings, French Revolutionaries, and emperors, who continued vandalizing Paris right into the modern age. When a ruler wanted something new he merrily tore down everything in his way.

ew cities can claim a tradition of urban vandalism nobler than that of Paris. Perhaps it’s genetic: archaeologists insist the Gauls burned their Seine-side settlements before going to battle, thus depriving rivals of the pleasure. Julius Caesar and his descendants endlessly reconfigured their fledgling city, as did generation upon generation of kings, French Revolutionaries, and emperors, who continued vandalizing Paris right into the modern age. When a ruler wanted something new he merrily tore down everything in his way.

But Parisians have not been immune to preservationist sentiments. For the past two hundred years or so those in command have usually prefaced their assaults by citing public safety, sanitation, or, that magic word, “modernity.” Many Paris connoisseurs think Emperor Napoléon III and his prefect Baron Haussmann were the archetypal modernizers: they flattened thousands of buildings for a variety of reasons, from bona fide health concerns to crowd control and rampant greed. Decried as a rape by sensitive souls such as poet Charles Baudelaire or Victor Hugo, “Haussmannization” was nonetheless carried out by visionary planners and skilled architects. Whatever they built was built to last.

What is less well publicized is that the vandal heritage, slowed occasionally by recession or war, has been the driving force behind each of the various French republics that followed the Second Empire. It peaked under the current “Fifth Republic,” which began in 1958. Predictably the orgy of state-sponsored speculation the new republic ushered in was dressed up as Haussmann-style modernization. This time it was not an emperor and a baron directing the show but an aging general and a little gray technocrat named Georges Pompidou.

Pompidou rose to power as De Gaulle’s right-hand man, moving in smooth succession from a 1958 advisory position to that of prime minister, before becoming president in 1969. A statesman, De Gaulle didn’t like cluttering his mind with minor concerns such as the economy, the environment, or urbanism. So he delegated. “Ask Pompidou,” he would say with a vague gesture.

Pompidou’s reign ended with his sudden death in 1974, meaning that he presided over France and the capital’s fortunes for sixteen years (Paris had no mayoral authority from 1871 to 1977). This was the height of

les trente glorieuses

—thirty glorious years of bull market.

When I hear someone say “Pompidou” I lift my eyes to Paris’s skyline and see the name writ large. Pompidou lives on in the opaque, sixty-story silhouette of the Tour Montparnasse and the nervy university complex of Jussieu that’s about half as tall. Look west and there’s Pompidou again, mastermind of the mock-Manhattan towers of La Défense. Of course, there are the multicolored pipes and Plexiglas tubes of the Pompidou Center at Beaubourg, a prime example of what was formerly (and without irony) called Brutalism, from the French word

brut

, as in raw or unfinished. That meant deconstructed structures with their guts exposed. Lower your eyes and you’ll see many minor examples of the Pompidou era, from unremarkable administrative carbuncles and low-income housing to the mirrored squalor of Le Forum des Halles.

But there’s more to Pompidou’s Paris than most people realize. The Georges Pompidou Expressway snakes along the Seine where leafy river ports once stood. The Boulevard Périphérique, originally the no-man’s-land outside the 1848 city walls, was slated to become a greenbelt until Pompidou had it transformed into an eight-lane cement moat that separates Paris from its surroundings. Facing La Défense alongside the Périphérique is the Porte-Maillot hotel, shopping, and convention center so dear to Pompidou. Though only a few decades old, it was judged ugly enough to deserve a multi-million-dollar facelift not long ago, and it’s still an eyesore.

The list of Pompidou-inspired marvels goes on. It includes much of the damage done to the Marais and other historic districts (where streets were systematically widened by destroying rows of townhouses). And don’t forget the Place d’Italie apartment blocks on Paris’s south side, seemingly lifted from outer Moscow, or the Front de Seine high-rise pseudo-Cubist clusters and garish shopping center at Beaugrenelle in the 15th arrondissement, not to mention the “nouvelle” but already crumbling Belleville, and much of what is now the blighted, high-crime suburban ring around Paris.

Actually, the city got off lightly. Many of Pompidou’s most outlandish schemes were abandoned because of public outcry, or because the great modernizer died while still in office, and his successor, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, either refused to carry them out or was in turn thwarted. Here are a handful of examples of what we missed: a spaghetti bowl of expressways with skyscrapers in their midst, extending from Les Halles to the Seine; a freeway atop the Canal Saint-Martin; a Left-Bank expressway from Tolbiac to the Pont Mirabeau; a bridge across the downstream tip of the Île de la Cité that would have obliterated the handsome Square du Vert Galant; the demolition of the entire Marais except for two churches and one townhouse; and, in 1966, Pompidou planned to build “Paris II,” a residential city conceived so that what was left of the real Paris could be gutted and refitted.

“It is up to the city to make way for the automobile,” Pompidou pronounced midway through his reign, “and not the other way around.” He spoke of “surgical themes” and “necessary transformations,” promising Parisians a modern metropolis to rival New York and London, made to the measure not of man, but of the machine.

To this day some people actually admire Pompidou’s heritage. So let’s be fair: He bequeathed the city the RER commuter-train system and lovely La Défense. He created the Nouvelles Villes satellite cities and a network of freeways any sprawling megalopolis would be proud of. He was a man of his mixed-up, paradoxical times, the days of atonal “classical” music, hard rock and “free jazz,” free love, Pop Art, Agent Orange, LSD, and the domino theory. Pompidou may have resided on the historic Île Saint-Louis in a luxury townhouse but he earnestly wanted a freeway in front of his picture windows—and almost got one. The automobile was his God.

Small and swarthy, with a perennial, wolfish grin wrapped around a smoldering cigarette, Georges Pompidou was in fact a provincial from the Massif Central. A lifelong overachiever, he graduated summa cum laude in Greek then fought alongside De Gaulle. After the war he proved his quiet brilliance by rising to CEO of the Banque Rothschild. In the meantime, he’d netted the

chicissime

Claude Jacqueline Cahour, who was later dubbed “the first modern First Lady of France” and the “godmother of French art”—contemporary art, needless to say. Hard to pigeonhole or place on the political spectrum, Pompidou was backed by some of the great French intellectuals. Literary icon André Malraux, the country’s first minister of culture, worked cheek-by-jowl with the little gray man whose real personality screamed in primary colors. Incredibly, Malraux’s celebrated urban conservation laws helped save the Marais, but he nonetheless signed the permits for many of Pompidou’s catastrophes, including the Tour Montparnasse.

“Pompidou said little and wrote nothing while Malraux talked too much and wrote too much,” noted historian and Pompidou-confidant Louis Chevalier in his still-controversial exposé

L’Assassinat de Paris

, first published in 1977. A chronicle of how the De Gaulle–Malraux–Pompidou troika massacred the city, the book points out that Pompidou was at heart a banker. The banks owned real estate and were cozy with building contractors. The rest of the riddle is easy.

Another intellectual bigwig of the postwar period who came to despise Pompidou was author Georges Pillement. In

Paris Poubelle

(“Garbage-Can Paris”) Pillement asserts that Pompidou was aware of—and possibly the source of—the systematic vandalism occurring in central Paris. The aim of that vandalism, theoretically, was to get neighborhoods declared unsafe so they could be bulldozed. In this scenario, Pompidou’s long-term plan was to transform Paris into

the

European business center, studded with Le Corbusier–style high-rises and veined by highways. Pompidou “seduced” Malraux with visions not of banal skyscrapers for businessmen but of neo-medieval towers.

If De Gaulle was king and Pompidou his white knight then Malraux was the court decorator and savant, writes Chevalier in

L’Assassinat de Paris

. In any case, Pompidou was firmly in control, pressing the right buttons: with De Gaulle he spoke of France’s renascent glory and with Malraux, who could have thwarted him, he wrapped his visions in the fluff of whimsy. Thirty-some years later the results—now cracking, rusting, and peeling—are plain to see.

A bad Chicago skyscraper set in what used to be an artists’ quarter of two-story workshops, the Tour Montparnasse is so brutally banal and clearly out of place that I’ve become almost protective of it. That familiar brownish hulk is an ever-visible reminder of what not to do in a historic European city. Several years ago rumors began spreading about the tower’s possible demolition. It is universally loathed and, worse from the city’s standpoint, has not been profitable. With this peril in mind I spent an hour wandering through the could-be-anywhere shopping center at the tower’s base, pondering what might replace it. Then I rode an elevator to the top floor.