Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light (24 page)

Read Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light Online

Authors: David Downie

Tags: #Travel, #Europe, #France, #Essays & Travelogues

Inaugurated in 1973, the tower feels like it’s about to deconstruct itself. No one appears to have celebrated its thirty-seventh birthday in 2010, but perhaps they’re awaiting the big 4–0. Several windows were missing, replaced by plywood panels. The fingerprints of the project’s Chicago-based designers were everywhere: this was a piece of 1960s–’70s Americana owned by the French, a typical De Gaulle–Pompidou act of defiance vis-à-vis the postwar period’s new global, English-speaking power.

Soon after the Eiffel Tower was built, novelist Guy de Maupassant began lunching in the panoramic restaurant there because, as he put it, it was the only place in town from which you could not see the Eiffel Tower. The same could be said for panoramic Montparnasse: the view is splendid and there’s no Montparnasse tower to be seen. Unhappily, amid the centuries-old mix of inner Paris that spreads below, you’re treated to a pigeon’s-eye view of Pompidou’s other creations. There is simply no escaping them. The 1965 Jussieu university complex, for example, almost obscures the handsome tree-lined alleys of the Jardin des Plantes behind it. And unless you’re as shortsighted as Pompidou himself, you can’t help staring at the paint-box innards of the Pompidou Center, whose construction entailed the demolition of the historic Beaubourg neighborhood.

As I crossed town along “Haussmannized” yet appealing boulevards toward the Pompidou Center I recalled the time I interviewed Renzo Piano, the center’s co-architect. “It was a joke,” Piano snorted, stroking his bushy beard. “A parody of technology … a great, insolent, irreverent provocation.”

Were Piano and fellow architect Richard Rogers really thumbing their noses at Pompidou and his technocrats? Maybe. Piano, I reflected, is an affable and clever man. He has had years to develop a convincing patter. His idea, he now says, was to create a place where the arts and other disciplines would mix and match—a culture factory. When people said that his building looked like a refinery Piano was delighted. As to the destruction of historic Beaubourg, Piano pointed out that Pompidou’s men had already wiped the slate.

Love it or hate it, the giant culture-refinery of Beaubourg has been a surprise success. Around seven million people visit it annually, loving it to death. French taxpayers like me spent tens of millions of dollars to restore it a few years ago, even though the building was barely into its twenties. Gaining admission to the Pompidou these days is a feat: typically the lines snake for a quarter mile through the sloping “piazza” out front, among the caricature artists, fire-eaters, and mimes. The high culture starts inside.

This time around I skipped the world-class museum displays and the vast library to look again at the building itself. Light streamed in through the thirty-foot windows. People floated by on escalators in Plexiglas tubes. Transparent elevators bobbed up and down. The color-coded pipes and ducts, another mock-industrial provocation, shone bright. For a moment I thought I’d stepped back into the caustic, gutsy, colorful seventies.

Luckily I hadn’t. I poked around the trendy, panoramic restaurant called Georges (a reference, perhaps, to Monsieur Pompidou?) but could not afford to sit down. From the viewing terrace, lower than that of Montparnasse, I could see the roofs of old Paris. Pompidou had disdained them and tried, with a large measure of success, to bring them down. Sadly, he never lived to see his namesake center completed: it opened in 1977, three years after his death. As I exited through the lobby I looked up at the round, deconstructed black-and-white Op Art portrait of Pompidou hanging there for all to see. His wolfish grin shifted as I passed.

In retrospect Pompidou’s most impressive achievement was not the building of the Tour Montparnasse or the Pompidou Center at Beaubourg; it was the eviction of the messy old general markets from Les Halles. Planners had been trying to get rid of them for decades. Once the market was gone, the area became a slum in short order. Soon thereafter the nineteenth-century glass-and-ironwork Baltard pavilions that had housed the market were flattened. Another decade went by before a seven-story subterranean RER train and Métro station—the world’s biggest underground station—and a shopping center with a sunken “forum” filled the “hole of Les Halles.”

I thought of Émile Zola as I rode a steeply raked escalator into the Forum’s pit. In his 1873 Rougon-Macquart series of novels Zola dubbed the old market

le ventre de Paris

—the guts or stomach of Paris. Apparently the site has permanent indigestion: it emanates an acrid stench. Some say it’s the disgruntled spirits of place. Others believe it’s the smell of oozing sewage, scented by disinfectants and bubbling fast-food fryers. Experts claim it’s the scent of decomposing limestone. In any case, at least the suburban adolescents, the hucksters, and the drug dealers surrounding me among the stained and broken cladding seemed to be enjoying the Forum. It’s soon to be rebuilt, after only thirty-some years of service.

I headed as fast as I could out of the area, the words of the governor of Rome Rutilius Claudius Namatianus, written around AD 415 as Rome collapsed, ringing in my ears: “Cities, too, can die.”

In the 1970s, critics of Pompidou pronounced Paris dead. But as I sipped a beer in a landmark building that would have been destroyed had Pompidou’s plans been carried out, another thought sprang to mind. Like the proverbial phoenix rising from the ashes, cities can also be reborn. Despite Les Halles, Montparnasse, and many a blighted suburb, it seemed to me that Paris was alive and ready to box its way through the twenty-first century. Now, if only the authorities would follow Pompidou’s precepts and dynamite his towers and shopping malls, then close the Seine-side expressways and transform the Périphérique into that mythical greenbelt, we’d really be talking modernity.

Keepers of the Craft: Paris Artisans

Gold is for the mistress—silver for the maid—

Copper for the craftsman cunning at his trade

.

“Good!” said the Baron, sitting in his hall

,

“But Iron—Cold Iron—is master of them all.”

—R

UDYARD

K

IPLING

,

Cold Iron

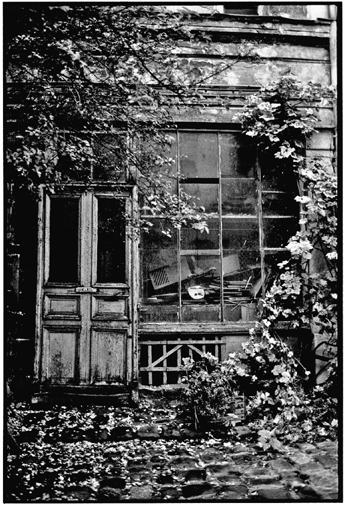

walked one day not too long ago down the picturesquely named Rue du Pont aux Choux—the street of the bridge of cabbages—near where I live in the Marais. As if in a dream I stepped through a set of steamed-up doors and witnessed a scene from Dante’s

walked one day not too long ago down the picturesquely named Rue du Pont aux Choux—the street of the bridge of cabbages—near where I live in the Marais. As if in a dream I stepped through a set of steamed-up doors and witnessed a scene from Dante’s

Inferno:

a blazing-hot furnace showered sparks into a dark workshop where leather-gloved men molded sheets of what I came to recognize as molten glass. A few hundred yards from the glassworks, in a seventeenth-century townhouse near Place des Vosges, I paused to watch a craftsman tap-tap-tapping with an old hammer, finishing a tooled-leather box. About half a mile east, still in the Marais, a solitary woman quietly carved antique wooden panels in an Alice-in-Wonderland workshop with sawdust reposing on wounded collectibles, yellowing plaster busts and cupids suspended on rusty wires.

To me, the word

artisan

evokes just such sepia-tinted images of yesteryear, of atmospheric ateliers where master craftsmen and eager apprentices toil into the night to create or restore goods at once useful and beautiful to behold. This is not the throwaway junk we’re used to, but the solid, desirable stuff of our forebears. Happily in Paris by some small miracle the craft tradition has survived not only the fall of the Ancien Régime and the advent of industrialization, but also the myriad manifestations of contemporary mass consumerism.

The French language is ambiguous when it comes to defining the term

artisan

. It can identify anyone from a plumber to a baker or a taxi driver. Often it simply means “independent contractor.” But when I use it I’m thinking of crafts people who fashion one-of-a-kind items, shunning large-scale production methods, and catering to clients directly in their workshops.

Over the past several decades I have been lucky enough to meet many skilled artisans in Paris: glassworkers, silver- and coppersmiths, bronze founders, ceramists, enamelers, painters of miniatures, cabinetmakers, leather workers, bookbinders, makers of stained-glass windows, hatters, fan-makers, engravers, gilders, ivory sculptors, violin- and lute-makers, saddle-makers, jewelers, goldsmiths, printers, and others still.

Several thousand artisans work today in central Paris, living proof of the superiority in many fields of man over machine.

One reason the craft tradition remains encouragingly resilient is apprenticeship. It continues in many workshops, though not in the nineteenth-century sense of indentured servitude. Parisian youngsters wouldn’t buy that. Almost anyone can learn at any age to be an adequate artisan. The key word is “adequate.” For many crafts—inlay and cabinetmaking, for example—the experts are unanimous in saying that budding craftsmen really must begin when very young in order to develop the muscles and reactions needed to mature into a master. So, in this digitalized, laser-guided world of ours, apprenticeship is still the most vital means for training young talents and passing craft secrets down the generations.

Apprenticeship is what the Compagnons du Devoir du Tour de France is all about. This four-hundred-year-old association has long intrigued me, in part because of its quirky window displays of roof beams, stones, or furniture at its headquarters behind the church of Saint-Gervais, a hundred yards east of city hall. Mostly, I’ve been drawn to the Compagnons because they resemble a medieval crafts guild. Only adepts, and I use the word intentionally, aged fifteen to twenty-five, may join. They must agree to spend up to ten years traveling around France learning their chosen trade from masters—bakers, tapestry makers, carriage builders, stone masons, locksmiths, roofers, carpenters, saddle-makers, plasterers, and so forth. Reportedly, there is no such thing as an unemployed Compagnon. After their tour of duty, once they have set up shop, they must agree to train other Compagnons.

There’s another reason the craft tradition survives in France, and especially in Paris: the handful of world-class technical institutions scattered around the country, with four in the capital alone. The most famous is l’École Boulle, named after Louis XIV’s court cabinetmaker André-Charles Boulle (1642–1732). The school was founded in 1886 to train cabinetmakers and workers in related trades. Today Boulle graduates might work in cabinetry or inlay, or venture into the fine arts, jewelry, or industrial design. One graduate I met works for Cartier, another was a member of the TGV high-speed train design team.

Other Paris crafts schools include the 140-year-old EPSAA (graphic arts and architecture); the even older École Duperré (fashion, textile design or printing, interior decoration, tapestry, ceramics); and the equally venerable École Supérieure Estienne (engraving, bookbinding and gilding, printing, illustration and graphic arts). Both Duperré and Estienne offer adult education courses, and if I weren’t so hopelessly incapable of working with my hands I would be tempted to retrain and recycle myself through one of them, perhaps as a bookbinder, or something equally out of step with the times.

Of course luxury goods are yet another reason—perhaps the main reason—French artisans continue to thrive. They work for companies such as Hermès, Cartier, or Louis Vuitton. Fashion designers, too, though a pernicious breed in my book, do their part to keep alive a variety of unlikely specialties such as

plumassiers

(feather decoration makers), leather workers, silk dyers, hat-makers and, yes, fan-makers.

There is usually a flip side to a happy story and in this case it is one of numbers: a mere twenty years ago there were almost twenty thousand crafts workers in Paris’ two main crafts districts alone, the Marais (comprising the 3rd and 4th arrondissements) and abutting Faubourg Saint-Antoine east of the Bastille (the 11th arrondissement). If several thousand remain, where have the others gone?

To find out, I decided to talk to a spokesperson at the government-funded SEMA (Société d’Encouragement aux Métiers d’Art), which is putatively in charge of developing local assistance programs for artisans all over France. “Where have they gone?” the startled bureaucrat repeated my question rhetorically—he was startled because I’d uncovered the official statistics. “To the suburbs, the provinces, or out of business!” SEMA confirmed that only a handful of Paris artisans actually create new, original goods, mostly for luxury manufacturers or fashion houses. Everyone else now earns his living by making replicas of antiques or doing restoration work for individual clients or the French government.