Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light (34 page)

Read Paris, Paris: Journey Into the City of Light Online

Authors: David Downie

Tags: #Travel, #Europe, #France, #Essays & Travelogues

Sidewalk Sundae: What Makes Paris Paris

Give Parisians water, fresh air, and shade!

—C

LAUDE

B

ARTHELOT

, Comte de Rambuteau, Prefect of Paris, 1830

[For the “collective,”] glossy enameled shop signs are a wall decoration as good as, if not better than, an oil painting in a bourgeois’s drawing room; walls with their “Post No Bills”

are its writing desk, newspaper stands its libraries, mailboxes its busts, benches its bedroom furniture, and the café terrace is the balcony from which it looks down on its household

.

—W

ALTER

B

ENJAMIN

, 1934

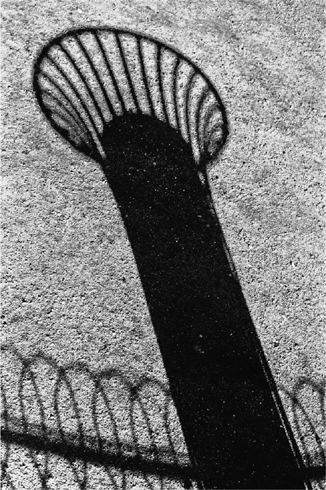

ay “Paris” and with the predictability of Pavlov’s dog millions the world round will bark “Eiffel Tower,” “Musée d’Orsay,” or “Louvre.” For many people, monuments and museums define what the French capital is all about. For me monuments are navigational tools in a cityscape whose character manifests itself in humble, vernacular realities: the alignment of façades, trees, and lampposts, and the placement on sidewalks and streets of signs, bus shelters, trash cans, toilettes, phone booths, benches, and bollards. Yes, bollards.

ay “Paris” and with the predictability of Pavlov’s dog millions the world round will bark “Eiffel Tower,” “Musée d’Orsay,” or “Louvre.” For many people, monuments and museums define what the French capital is all about. For me monuments are navigational tools in a cityscape whose character manifests itself in humble, vernacular realities: the alignment of façades, trees, and lampposts, and the placement on sidewalks and streets of signs, bus shelters, trash cans, toilettes, phone booths, benches, and bollards. Yes, bollards.

An open-air collection of cultural ID cards, it’s the sidewalks of the city and their unsung “furniture” that help make Paris, Paris. Stand on just about any corner in town and you’ll know instinctively that you’re not in Lyon or Lille, let alone London or Lisbon. Like minor artworks only a curator can love, each piece of Paris’s urban décor reflects the spirit and needs of its day and provides insight into the city’s past, present, and future.

Take the bollards, for instance, those unsightly lumps of stone or cement that the French lovingly call

bornes

. Unfamiliar to most nations, like the proverbial pearls before swine

bornes

tell more about Parisians and their culture than do the contents of most museums. For one thing,

bornes

and their phallic brothers

les poteaux

—alias

les bittes

, those serried ranks of spindly brown posts bristling on pavements—are the only effective means of keeping cars from invading the territory of pedestrians. Left to their own devices Parisian drivers would mount

les trottoirs

and park everywhere and anywhere, including on your toes.

Bornes

have been around for centuries: the first daguerreotype, from 1838, shows rows of them on Boulevard du Temple near what’s now Place de la République.

Bornes

gave rise to that quintessentially French expression,

dépasser les bornes

—meaning beyond restraint, beyond reason, beyond the control of the bureaucrats whose job it is to enforce

liberté, égalité

, and

fraternité

. The argot meaning of

bitte

is obvious enough. Real and metaphorical, blocky

bornes

and phallic

bittes

are only one element of a complex system of barriers and signage whose purpose is to restrain, thwart, and redirect unruly natives.

In 1910 the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, bemused by the rapidity of technological progress in street lighting, only half-jokingly proposed that the City of Light create a museum of lampposts and related equipment. Apollinaire saw perhaps a dozen models of lamp on the city’s streets, from ancient oil lanterns mounted on pulleys to pressurized-gas burners on elegant ironwork posts and, of later manufacture, a variety of electric types, including Hector Guimard’s praying mantis–like illuminated 1900 Métro entrances. Since Apollinaire’s death in 1918 at least another dozen generations of lighting fixtures have been added to the mix. More surprising than this continuing tech evolution is the cultural tendency to adapt the new to the old, to convert a cast-iron gas lamp of the 1850s again and again, for instance, thereby demonstrating an attachment to the past only in part ascribable to economics.

My personal sidewalk epiphany occurred while I was researching the origins of the nickname Ville Lumière—City of Light. A bulb flickered on in my brain, highlighting those proverbial pearls scattered before my snout. I began to take notice of Paris’s peculiar décor and realized that, just as the City of Light has a luminous identity created by engineers and designers, so too it has dozens of architects, planners, and administrators in an array of interlocking government departments whose life’s work is the creation, placement, and upkeep of street furniture that declares “You’re in Paris,” nowhere else. Now, whenever I step beyond the

bornes

separating my building’s courtyard from the public realm, I think about the crucifixion of Saint Andrew as represented in the city’s metal crossbars that protect sidewalks from traffic on the streets (they show a capital X on their sides and are found at nearly every intersection). I ponder the age-old symbolism of the red (passion, danger), yellow (caution), and green (hope, safety) of stoplights, first used here in 1923. I delight in the double-sided 1850s-style benches draped with young lovers or with garrulous geezers. I weigh the relative merits of granite or asphalt underfoot as I sidestep horizontal pollution, and wonder what Paris was like before it had sidewalks, a relatively recent invention. With a curse I blink at the luminous, revolving, flashing outdoor advertising on a thousand panels, poles, and columns, and marvel at the hideousness of the so-called

sanisette

toilets encased in concrete bunkers.

The ad panels and toilets (plus many other contemporary sidewalk items) were designed for and are operated by JC Decaux, the world’s biggest street furniture supplier and Europe’s top outdoor advertising agency. In concert with a municipal committee, they hired prize-winning British architect Norman Foster to come up with his glassy bus shelters, international design star Philippe Starck to excogitate faux-Gallic canoe paddles (with potted histories of Paris sites), and Jean-Michel Wilmotte to replace the benches, lighting, and signals on the upper end of the Champs-Elysées. Foster bus shelters, intentionally unobtrusive, are now in many cities worldwide. Wilmotte’s furniture is nice enough but could be anywhere. And the best that can be said of the Starck paddles is, they supply useful information.

I’m not predisposed to reactionary sentiments and have nothing against current design gurus. But when it comes to the objects on Paris’s sidewalks, generally speaking the older they are the better. Whether or not you side with Victor Hugo and despise Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann for the way he destroyed medieval Paris during the Second Empire, sooner or later you’ll have to admit that Napoléon III’s zealous prefect did an impressive job equipping the city from 1853 to 1870 with site-specific, only-in-Paris fountains, benches, kiosks, and newsstands set up under freshly planted trees, on novel sidewalks, and in squares or parks, for the delectation of all social classes.

It was Haussmann’s head engineer Jean-Charles-Adolph Alphand and architect Jean-Antoine-Gabriel Davioud who masterminded the transformation of public areas into “flower-filled salons” where beleaguered Parisians and their horses could quench their thirst, relieve themselves, breathe fresh air, rest in the shade of more than one hundred thousand trees, and, if they had time to spare, watch the world go by. Davioud may not be a household name, but city planners everywhere hail him as the unwitting father of “street furniture” (the binomial was coined by Frenchman Jean-Claude Decaux in the 1960s). To his mind, Davioud was merely “decorating” the capital. At a distance of more than a century since Davioud’s death, if Paris can still be said to have its own unmistakable street-level look and feel, that achievement is largely attributable to him.

Despite his lengthy name and Prix de Rome pedigree, Davioud was self-effacing, rarely signing his work. After furnishing Paris’s sidewalks, he dashed off blueprints for twenty-four parks and garden squares, detailing everything from the paths, gates, and grilles to the tree-corsets, water fountains, and amusement stands—an onion dome here, a playful mask there, and plenty of foliage faux and real. Then he turned his hand to the twin theaters at Châtelet, and the fountains of Place Saint-Michel, l’Observatoire, and Daumesnil. Dozens of the old green pavilions, rotundas, and shelters in Paris are of his conception. So all-encompassing and lasting is Davioud’s influence that it’s tough to imagine a Paris street before him. But his designs didn’t come from nowhere. They were rooted in European history, drawing on the Italian Renaissance and the English reinterpretation of it that followed the eighteenth-century Grand Tour.

Rewind to the preindustrial Paris of the Ancien Régime, a city of under half a million, with layout and building styles still marked by the Gallo-Roman Lutetia, with medieval and Renaissance overlays. On the spider’s web of alleys spreading outward from Notre-Dame there are few signs and no sidewalks. Gutters in the center of dirt roads run black with sewage. Garbage is piled high against the half-timbered buildings. The air reeks of boiled cabbage and the burning rapeseed oil that fuels the lanterns hung from scabrous façades. In the shadowy rankness, carriages thunder by scattering pedestrians whose only refuges are rows of stone bollards, posts, and mounting blocks. There are no benches or trees outside the sealed royal enclave of the Tuileries or the private gardens of the rich. Public fountains are besieged: indoor plumbing hasn’t been invented. Most wells are contaminated. Water-bearers serve neighborhoods that have no drinking water. On the edge of this squalor, the sole neighborhood conceived for pedestrians and pleasure-seekers is Boulevard du Temple, a chaotic esplanade built atop former bastions, where five rows of sycamores from the late 1600s shade theaters and café terraces.

Fast forward from the mid-1700s into the early industrial age, when hundreds of thousands of French provincials driven off the land begin moving to Paris to work in factories. Suddenly, the great unwashed are swarming onto the streets. The number of traffic accidents skyrockets. An anonymous writer in

L’Espion des boulevards

notes that, “The pedestrian lacking agility is a dead man!” Cholera spreads through overcrowded tenements, killing thousands. Old Paris has become a hellhole of disease and famine, wracked by riots culminating in the Glorious Revolution of July 1830.

Enter Claude Barthelot, Comte de Rambuteau, prefect of Paris as of 1830. Upon taking office a mere 146 drinking fountains supply a population nearing one million. Only three streets have sidewalks. Rambuteau’s slogan is “Give Parisians water, fresh air, and shade!” A chronicler of the day quips that the count “would rather have his own teeth pulled than uproot trees he’s planted.” It is Rambuteau who begins the process of “sanitizing” medieval Paris: the road that bears his name, driven through Beaubourg in 1838, destroys six streets of the eleventh and twelfth centuries and scores of buildings. Under Rambuteau, in 1841, the Faubourg Saint-Martin becomes the first neighborhood to get a complete set of “furniture”: sidewalks, lights, benches, trees, drinking fountains and, what is considered a miracle of hygiene, urinals. By the time Napoléon III fires him, Rambuteau can report totals of 1,840 fountains, about 150 miles of sidewalks, hundreds of benches, and thousands of trees.

These are the tumultuous years captured on polished metal plates by pioneering photographer Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, inventor of the daguerreotype. His studio just happens to be sited high above Boulevard du Temple. Continuity? In Paris the historic present tense reaches far beyond grammar. If you get out a magnifying glass and study the images Daguerre produced in Spring 1838, you’ll see

bornes

edging the road just as they do now in many places, iron corsets supporting saplings, and streetlamps with fishbowl globes held aloft by lyre-headed poles identical to ones in use today.

However hard he tried, Rambuteau’s efforts failed to cure Paris’s growing pains. The city was rocked by unrest again in 1848. The new government was soon subverted from within, and, in 1852, Charles-Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte declared himself emperor. An enlightened despot, Napoléon III was bent on making Paris the world’s most modern city. He assigned the task to Baron Haussmann.