Paul Revere's Ride (18 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

Dr. Joseph Warren (1741-75), was a gentleman-revolutionary. Admired by his friends and respected even by his enemies, he contributed a quality of character to the Whig cause. This animated oil sketch by John Singleton Copley occupied the place of honor over the parlor fireplace in the Adams family home. Courtesy of the National Park Service, Adams National Historic Site, Quincy, Massachusetts.

We shall never know with certainty the name of Doctor Warren’s informer, but circumstantial evidence strongly suggests that it was none other than Margaret Kemble Gage, the American wife of General Gage. This lady had long felt cruelly divided by the growing rift between Britain and America. Later she confided to a close friend that her feelings were those spoken by the lady Blanche in Shakespeare’s

King John:

The Sun’s o’ercast with blood; fair day, adieu!

Which is the side that I must go withal?

I am with both: each army hath a hand;

And in their rage, I having hold of both,

They whirl asunder and dismember me. …

Whoever wins, on that side shall I lose.

Assured loss, before the match be played.

9

Margaret Gage made no secret of her deep distress. In 1775, she told a gentleman that “she hoped her husband would never be the instrument of sacrificing the lives of her countrymen.”

10

Her loyalty came to be suspected by both sides. The well-informed Roxbury clergyman William Gordon wrote that Dr. Warren’s spy was “a daughter of liberty unequally yoked in the point of politics.”

11

Many British officers, including Lord Percy and General Henry Clinton, believed that General Gage was “betrayed on this occasion” by someone very near to him. Some strongly suspected his wife.

12

Even Gage himself appears to have formed his own suspicions. Earlier that same evening, he had summoned Lord Percy and told him that he was sending an expedition to Concord “to seize the stores,” Percy was admonished tell nobody—the mission was to remain a “profound secret.” As he left the meeting and walked toward his quarters, he saw a knot of eight or ten Boston men talking earnestly together on the Common. Percy approached them to learn what they were discussing. One man said:

“The British troops have marched, but will miss their aim,”

“What aim?” Lord Percy demanded.

“Why, the cannon at Concord.”

Percy was shocked. He hastened back to the general, and told him that the mission had been compromised. Gage cried out in anguish that “his confidence had been betrayed, for he had communicated his design to one person only,” besides Percy himself.

13

Before this fatal day, Gage had been devoted to his beautiful and caring wife. But after the Regulars returned from Concord, he ordered her away from him. Margaret was packed aboard a

ship called

Charming Nancy

and sent to Britain, while the General remained in America for another long and painful year. An estrangement followed after Gage’s return. All of this circumstantial evidence suggests that it is highly probable, though far from certain, that Doctor Warren’s informer was indeed Margaret Kemble Gage—a lady of divided loyalties to both her husband and her native land.

14

After hearing from his secret source, Dr. Warren sent an urgent message to Paul Revere, asking him to come at once. The time was between 9 and 10 o’clock when Paul Revere hurried across town. “Doctor Warren sent in great haste for me,” Revere later recalled, “and begged that I would immediately set off for Lexington, where Messrs Hancock and Adams were, and acquaint them of the movement, and that it was thought they were the objects.”

15

Paul Revere’s primary mission was not to alarm the countryside. His specific purpose was to warn Samuel Adams and John Hancock, who were thought to be the objects of the expedition. Concord and its military stores were also mentioned to Revere, but only in a secondary way.

16

Warren appears to have known or suspected that British officers were patrolling the roads west of Boston. To be sure that the message got through, he told Revere that he was sending duplicate dispatches by different routes. One message had been entrusted to William Dawes, a Boston tanner. Dawes was not a leader as prominent as Revere, but he was a loyal Whig, whose business often took him through the British checkpoint on Boston Neck. As a consequence the guard knew him. He was already on his way when Revere reached Doctor Warren’s surgery. Another copy of the same dispatch may have been carried by a third man.

17

Dawes and Revere carried written messages, which Lexington’s Congregational minister later copied into his records: “A large body of the King’s troops (supposed to be a brigade of about 12, or 1500) were embarked in boats from Boston, and gone to land at Lechmere’s point.” Warren’s estimate exaggerated the strength of the British expedition, but was accurate in every other detail.

18

The messengers took different routes. William Dawes left town across Boston Neck—no small feat. He had to pass a narrow gate, closely guarded by British sentries who stopped all suspicious travelers. Dawes was remembered to have been “mounted on a slow-jogging horse, with saddle-bags behind him, and a large

flapped hat upon his head to resemble a countryman on a journey.”

19

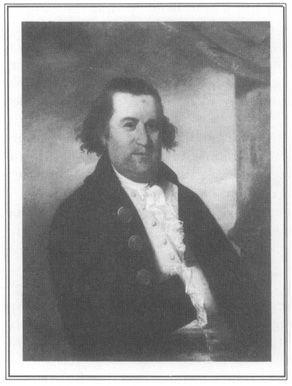

William Dawes, Jr. (1745-99), was one of many Whig “expresses” who carried the Lexington Alarm. A Boston tanner of old Puritan and East Anglian stock, he was asked to be a courier on April 18, perhaps because his work often took him through the British “lines” on Boston Neck, and he knew many of the guard. (Evanston Historical Society)

Some say he attached himself to another party; others, that he knew the sergeant of the guard and managed to talk his way through. According to one account, a few moments after he passed the British sentries, orders arrived at the guardhouse, stopping all movement out of town. Once safely across the Neck, William Dawes eluded the British patrols in Roxbury, and rode west through Brookline to the Great Bridge that spanned the Charles River at Cambridge.

20

Paul Revere made ready to leave in a different direction, by boat to Charlestown. His journey was not a solitary act. Many people in Boston helped him on his way—so many that Paul Revere’s ride was truly a collective effort. He would be very much surprised by his modern image as the lone rider of the Revolution.

Revere had anticipated that the Regulars might try to stop all communications between Boston and the countryside. He would have remembered keenly his failure to warn the people of Salem in February, when Colonel Leslie’s men held three of his fellow

mechanics prisoner in Boston harbor until the expedition was on its way. The problem had been percolating in his mind for several weeks. Only the Sunday before, on his way home from Concord, Paul Revere had stopped at Charlestown and discussed the matter at length with Colonel William Conant and the Whig leaders of that town. Together they worked out a set of contingency plans for warning the country of any British expedition, even if no courier was able to leave town.

21

Later Paul Revere recalled, “I agreed with a Colonel Conant and some other gentlemen, that if the British went out by water, we would shew two lanthorns in the North Church steeple, and if by land, one, as a signal, for we were apprehensive it would be difficult to cross the Charles River, or git over Boston neck.”

22

Revere called his signal lights “lanthorns,” an archaic expression in England by 1775, but still widely used in Massachusetts, where translucent lantern-sides continued to be made in the old-fashioned way from paper-thin slices of cow-horn. These primitive devices emitted a dim, uncertain light. The problem was to make them visible from Boston to Charlestown, more than a quarter-mile distant across the water.

23

Paul Revere and his friends agreed that the best place to display such a signal was in the steeple of Christ Church, commonly called the Old North Church. In 1775 it was Boston’s tallest building. Its location in the North End made it clearly visible in Charlestown across the water.

24

But there was a problem. Christ Church was Anglican. Its rector was an outspoken Loyalist, so unpopular with his congregation that his salary had been stopped and the Church closed. As always, Paul Revere had several friends who could help. He was acquainted with a vestryman of Christ Church named Captain John Pulling, a staunch Whig and a member of the North End Caucus. Pulling agreed to help.

25

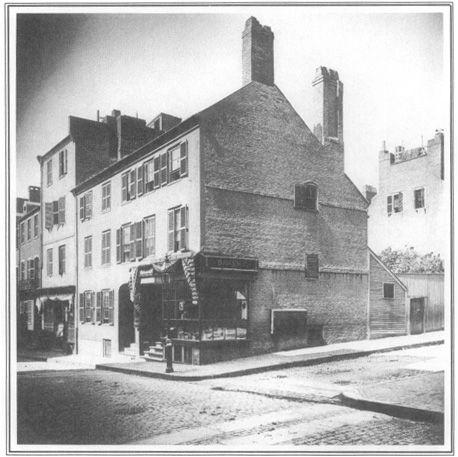

Revere also knew the sexton of Christ Church, a young artisan named Robert Newman, who came from a prominent North End family that was down on its luck in 1775. Like many Boston families, the Newmans were a transatlantic cousinage, with branches in East Anglia and Massachusetts. Robert Newman’s uncle was Sir Thomas Newman, Lord Mayor of Norwich. His father had been a prosperous Boston merchant, who built a big three-story brick house in the North End, with massive chimney stacks and a cupola that looked out upon his ships in the harbor. When Robert Newman was two years old, the family’s fortunes were shattered by his father’s death. His mother was forced to convert their handsome

home into a boarding house, and Robert was apprenticed to a maker of leather breeches. Like many others in Boston, the Newman family was hard-pressed in 1775. They earned a few shillings by renting rooms to British officers, whom they disliked and resented. Robert Newman was unable to find work in his trade and could get employment only as a church sexton, a job that he despised. When Paul Revere asked him to help, he was happy to agree. Revere had chosen well. Robert Newman was known in the town as “a man of few words,” but “prompt and active, capable of doing whatever Paul Revere wished to have done.”

26

On the afternoon of April 18, Revere alerted Newman and Pulling, and also another friend and neighbor, Thomas Bernard, and asked them to help with the lanterns. They were warned to be ready that night.

27

It was about 10 o’clock in the evening when Paul Revere left Dr. Warren’s surgery. He went quickly to the Newman house at the corner of Salem and Sheafe streets. As he approached the building, he peered through the windows and was startled to see a party of British officers who boarded with Mrs. Newman playing cards at a parlor table and laughing boisterously among themselves. Revere hesitated for a moment, then went round to the back of the house, and slipped through an iron gate into a dark garden, wondering what to do next.

Suddenly, Newman stepped out of the shadows. The young man explained that when the officers sat down to their cards, he pretended to go to bed early. The agile young sexton retired upstairs to his chamber, opened a window, climbed outside, and dropped as silently as a cat to the garden below. There he met Pulling and Bernard, and waited for Revere to arrive.

28

Revere told his friends to go into the church and hang two lanterns in the steeple window on the north side facing Charlestown. He did not stay with them, but hurried away toward his own home. The men left him and walked across the street to the Old North Church. Robert Newman tugged his great sexton’s key out of his pocket and unlocked the heavy door. He and Captain Pulling slipped inside, while Thomas Bernard stood guard.

Newman had found two square metal lanterns with clear glass lenses, so small that they could barely hold the stump of a small candle. Earlier that day he had carefully prepared the lanterns, and hidden them in a church closet. Newman took them from their hiding place. The men hung the lanterns round their necks by leather thongs, and stuffed flint and steel and tinder boxes into

their pockets. They climbed the creaking stairs, 154 of them, high into the church tower. At the top of the stairs they drew out their flints, and with a few practised strokes sent a stream of sparks into a nest of dry tinder. Gently they blew the glowing tinder into a flame, and lighted the candles.