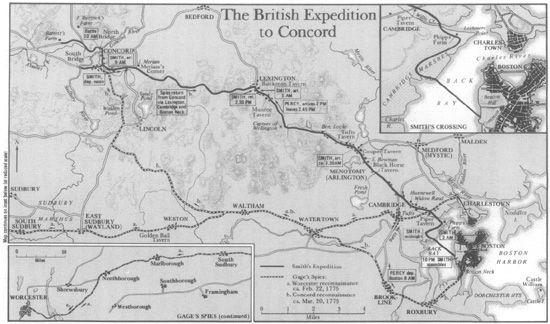

Paul Revere's Ride (21 page)

Read Paul Revere's Ride Online

Authors: David Hackett Fischer

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #History, #United States, #Historical, #Revolutionary Period (1775-1800), #Art, #Painting, #Techniques

This expedition … from beginning to end was as ill-planned and ill-executed as it was possible to be.

—Lieutenant John Barker, 4th (King’s Own) Foot, 1775

EARLIER THAT EVENING, while Paul Revere and William Dawes were preparing to leave Boston, General Gage set his army in motion. Many precautions were taken to prevent discovery. The soldiers were awakened in their beds, “sergeants putting their hands on them, and whispering gently to them.”

1

The men dressed quietly, strapped on their full cartridge boxes, and picked up their heavy muskets. They were ordered to leave their knapsacks behind, and to carry one day’s provisions in their haversacks. One soldier remembered that he was told to bring 36 rounds of powder and ball.

2

The British soldiers were “conducted by a back-way out of their barracks, without the knowledge of their comrades, and without the observation of the sentries.” The men were ordered to move in small parties, so as not to alarm the town. They “walked through the street with the utmost silence. It being about 10 o’clock, no sound was heard but of their feet. A dog that happened to bark, was instantly killed with a bayonet.”

3

The Regulars made their way to a rendezvous chosen for its remoteness—an empty beach on the edge of the Back Bay, near

Boston’s new powder house in “the most unfrequented part of town.” When challenged by the sentries, they answered with the evening’s countersign, “Patrole.”

4

First to arrive were the flank companies of the Royal Welch Fusiliers. Their regimental adjutant Frederick Mackenzie regarded punctuality as a point of honor. Next came the King’s Own, who bivouacked near Boston Common, close by the beach. Other companies came in from Fort Hill, and some from Boston Neck, and a few from the Warehouse Barracks near Long Wharf. Several companies arrived from the North End after forming up near the North Church. They were the troops who had nearly intercepted Robert Newman and Captain Pulling. Altogether, the expedition numbered between 800 and 900 Regulars in twenty-one companies, plus a few volunteers and Loyalist guides.

5

These were picked men, the flower of General Gage’s army. In that era most regiments of British infantry had two elite units: a grenadier company and a light infantry company. The grenadiers were big men, chosen for size and strength. In the earlier 18th century their special task had been to hurl heavy hand grenades at the enemy, hence their name and stature. By 1775 they had lost that role and gained another, as shock troops whose mission was to lead the bloody assaults that shattered an enemy line, or captured a fortification by a

coup de main.

The light infantry companies were a different elite—the most agile and active men, selected for fitness, energy and enterprise. They had been added to every British regiment in 1771 to serve as skirmishers and flank guards, partly at the urging of General Gage. In some regiments these men carried long-barreled muskets, which were more accurate at longer distances than the standard issue Tower musket. Some were equipped with hatchets modeled on American tomahawks.

In the French and Indian War, British commanders had sometimes collected their light infantry and grenadier companies into provisional units for special service. General Gage followed this common procedure. His Concord expedition consisted of eleven companies of grenadiers and ten of light infantry. That practice had the advantage of bringing together the best soldiers in the army. But it also had a major weakness. Officers and men of different regiments were not used to working with one another. They found themselves commanded by strangers, and compelled to fight alongside other units whom they did not know or trust. The regimental spirit that was carefully cultivated in the British

army worked against the cohesion of ad hoc units. Further, the normal chain of command was broken above the company level, and the complex evolutions of 18th-century warfare sometimes dissolved in confusion.

That confusion began to appear in the first moments of the Concord expedition, when the companies came together on Boston’s Back Bay. The 23rd’s regimental adjutant, Frederick Mackenzie, was appalled by the disorder he met on the beach. He found no officer of high rank firmly in command of the embarkation, and separate companies straggling aimlessly. The junior officers had been told nothing about where they were going or what they were to do. Lieutenant Barker of the 4th (King’s Own) wrote, “Few but the commanding officers knew what expedition we were going upon.”

6

The navy was there in good time, but Mackenzie counted only twenty ships’ boats, not nearly enough to carry the entire force in a single crossing. Two trips were needed to move everyone across the water. Mackenzie peered across the dark river toward the opposite shore, and discovered still another problem that had not been anticipated. General Gage’s staff had selected the crossing point mainly for secrecy. It ran from the most secluded spot in Boston across the Back Bay to a lonely beach on Lechmere Point in Cambridge, inhabited only by a single isolated farmstead known as the Phips farm.

7

The bay was broad and shallow at that point. The boats’ crews had to row more than a mile on a diagonal downstream course, against a rising Spring tide that was flowing up the Charles estuary. The Navy’s longboats were clumsy, heavy craft, built for strength and stability in the open sea. They were ordered to be tied together, bow to stern, in strings of three or four. That precaution was thought necessary to keep coxswains from losing their way in the dark, but it made the crossing even slower when speed was vital to success.

8

The soldiers were packed into the boats so tightly that there was no room to sit down. The vessels settled deep in the water until their gunwales were nearly awash. In the center of each boat the men stood quietly, their red coats nearly black in the moonlight and their long muskets slanting upward toward the bright sky. In the sternsheets beardless midshipmen whispered commands to weatherbeaten seamen while heavy ash oars creaked rhythmically against sturdy locust tholepins.

As the boats approached Lechmere Point, they went aground in shallow water that was nearly knee deep. The soldiers climbed into the river and waded awkwardly ashore, muskets held at high port. Then the boats backed off, and returned for another load. It was slow and painful work. Not until midnight was every man landed. Two precious hours had been spent crossing the Charles River.

On the Cambridge shore there was another scene of confusion as officers and sergeants struggled to form their broken companies. The commander, Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith, looked on with horror at the disorder that surrounded him. He was what another army in a later time would call a book soldier— methodical, cautious, and careful—an officer much to General Gage’s liking. That night, when time was of the essence, Colonel Smith ordered each company to assemble in a predetermined order on the beach. First came the light infantry of his own 10th Foot, then the other companies of light infantry in order of their regimental number, and the heavy grenadiers in the same sequence. This tidy arrangement was not Colonel Smith’s private obsession. It was a point of regimental pride in the British army. A regiment’s number indicated its seniority. The 4th (King’s Own) Foot had the lowest number that night, then the 5th, and others in numerical order. More time was lost as units jockeyed back and forth.

9

At last every company was in its proper place, and the men were ordered to march. They advanced painfully in their soggy gaiters and square-toed shoes full of brackish river water. As they left the beach, the men discovered to their surprise that they had been landed squarely in the middle of the “marshes of Cambridge.”

10

Their landing zone was sparsely inhabited because it was a swamp.

The men tried to move along the river’s edge where the footing seemed more solid than in the swamp itself. But the slippery beach pebbles were treacherous underfoot, and the thick river mud sucked at their heavy shoes. The tide was still high. From time to time the column found itself plunging into the water again. One officer recalled that their route took them “at first through some swamps and slips of the sea,” and “they were obliged to wade, halfway up their thighs, through two inlets.” Lieutenant Barker was one of the lucky ones. He remembered that his company was wet merely “to our knees,” Another officer recalled that his men were soaked “up to their middles.”

11

At last they came to a rough farm track that ran through the

marsh. The road was soft and wet, but at least it resembled terra firma. Here Colonel Smith halted his men yet again, while he waited for the navy to deliver two days’ provisions that had been prepared aboard ships in the harbor to avoid discovery. The Regulars stood quietly in the mud with the fatalism that is part of every soldier’s life, while sergeants prowled restlessly through the ranks, making sure that every infantryman had 36 rounds and a full cartridge box. The men were increasingly miserable. It was not a cold night by New England standards, but the men were sopping wet and a chill wind was blowing. They began to tremble in their wet uniforms, which were uncomfortable enough, even when dry.

The uniform of the British soldier in 1775 might have been designed by some demonic tailor who had sworn sartorial vengeance upon the human frame. The grenadiers wore towering caps of bearskin (later coonskin for Fusiliers), adorned with white metal faceplates and colorful cords and tassels, and blazoned at the back with their regimental number on embossed metal disks. Their headgear was designed partly to allow muskets to be slung easily, but its major purpose was to magnify the height of the men who wore them. On active service the caps were awkward and top-heavy. They were also costly to replace, and had to be protected in the field with painted canvas covers—caps for caps, which were slung from a belt when not in use.

The light infantry wore tight helmets of black leather, adorned with feathers or horsehair crests, and constructed with whimsical peaks in front or behind, according to the fancy of the regimental commander. This headgear was less awkward than the bearskins of the grenadiers, but it offered little protection against the rain, and tended to crack in the sun. When wet the leather shrank painfully, gripping the head like a vise.

The ordinary rank and file were called “hat companies” after their standard-issue cocked hats. According to the prevailing fashion in 1775, they were worn too small to fit snugly around the crown, and merely perched on top of the head. To keep them from tumbling off, the hats had to be fastened to the hair by tapes, and hooks and eyes.

The hair itself was dressed according to the taste of each colonel. In some regiments it was powdered white; in others it was congealed with gleaming black grease. Mostly it was plaited or “clubbed” into a pigtail, doubled on itself, and tied neatly with ribbon. Bald men, and even those with thinning hair were required to

wear switches. The neck was swathed in tight stocks of horsehair or velvet that came nearly to the chin.

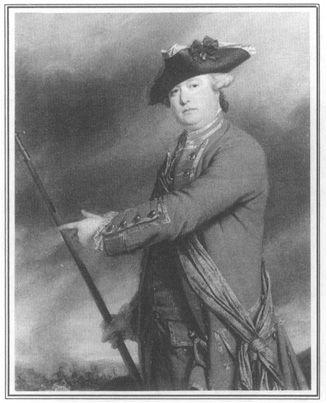

Lt. Col. Francis Smith of the loth Foot commanded the British expedition to Concord. A veteran of 28 years’ service, he joined in 1747 and saw much active duty. Some subordinates complained that he was fat, slow, stupid, and selfindulgent. Others including General Gage liked his prudence, caution, gravitas, and gentility. Both sets of qualities might be found in this painting, eleven years earlier. It is dated 1764, and hangs today in the British National Army Museum, Chelsea.

These men who stood in the muddy marshes of Cambridge wore snow white linen that had been changed only the day before. Every Wednesday and Sunday fresh linen was put on throughout the British army. They also were issued white or buff-colored waistcoats and breeches which were ordered to be kept immaculate on pain of a flogging. Later in the war, British soldiers were allowed to wear coveralls or loose “trowsers” on active service.

The most distinctive part of the uniform was the heavy red coat. For grenadiers and line companies this was a garment with long tails that descended nearly to the knee. The light infantry wore short jackets that ended at the hip, and were much preferred on active service. Later in the Revolution, General John Burgoyne ordered all his men to cut down their coats into jackets. Contemporary illustrations commonly show that the red coats of 1775 were worn very tight, according to the 18th-century fashion. They were supposed to be preshrunk, but after exposure to rain they shrank again, sometimes so much that the men found it painful to move their arms.